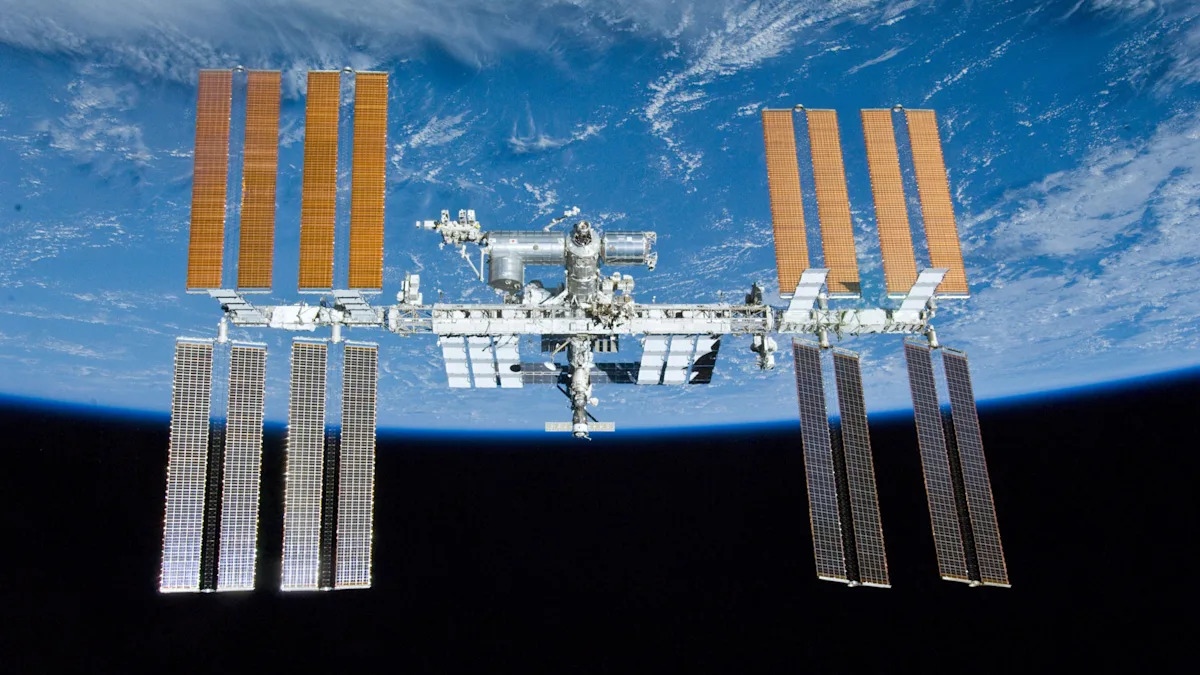

Scientists have infected bacteria with a virus aboard the International Space Station to see how they would interact in microgravity, and the results were surprising. Without gravity-inspired mixing of viral and bacterial cultures, the rate of infection and evolution slowed dramatically, per the researchers’ paper in PLOS Biology. Viruses, therefore, tended to evolve to more easily grab hold of bacterial cells, while those same bacteria developed countermeasures to resist viral contact.

Through their study, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the space biotechnology firm Rhodium Scientific found that cultures behaved very differently in space than they do on Earth. This was largely due to the ISS’s near-complete lack of gravity. On Earth, convection causes warmer fluids to rise and colder ones to sink, thereby facilitating interactions between viral phages and bacteria; this promotes infection, growth, and evolution. Without that effect in microgravity, everything behaved far more sluggishly.

The bacteria in this case were E. coli and its infecting phage, “T7.” Despite difficulties in finding infection hosts, the viruses adapted quickly to their new environment and developed novel methods for attaching to bacteria. Those E. coli cultures, in turn, developed unique defences, such as tweaking their receptors.

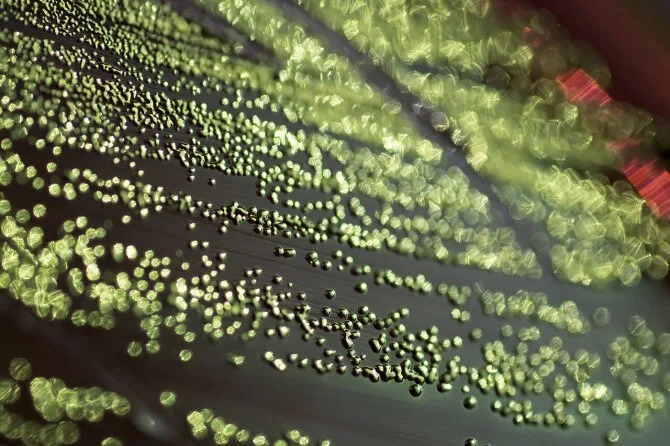

E. coli growing on Eosin methylene blue media.

E. coli growing on Eosin methylene blue media. Credit: Gene Drendel/Wikimedia Commons

It’s hoped that studying bacteria and viruses in different environments (including microgravity) might inspire new phage-based treatments for infections and a range of other maladies. Indeed, this early experiment may have already inspired one. When the bacteria and phages were returned to Earth, it was unknown whether these unique evolutions would increase their relative effectiveness against Earth-based counterparts. But the unique attachment mechanisms of space-based viruses have actually proved more effective at targeting the bacteria that cause urinary tract infections.

“These results show how space can help us improve the activity of phage therapies,” said Charlie Mo, an assistant professor in the Department of Bacteriology at UWMadison who was not involved in the study.

The big caveat here, though, is cost. It’s prohibitively expensive to get cultures into orbit and bring them home safely without contamination. New technologies for space-based manufacturing and sample recovery are being developed, though. As space becomes cheaper to access, whole new therapies and medical treatments could be discovered through these kinds of experiments.