Generally, you get two versions of England in art: it’s either bucolic vistas, rolling hills, babbling brooks and gambolling sheep – or it’s downtrodden, browbeaten, grim poverty and misery. But Beryl Cook saw something else in all the drizzle and grey of this damp old country: she saw joy.

The thing is, joy doesn’t carry the same critical, conceptual heft in art circles as more serious subjects, so Cook has always been a bit brushed off by the art crowd. They saw her as postcards and posters for the unwashed, uncultured masses, not high art for the high-minded. But she didn’t care: she succeeded as a self-taught documenter of English life despite any disdain she might have encountered. And now, on what would have been her 100th birthday, her home town of Plymouth is throwing her a big celebratory bash.

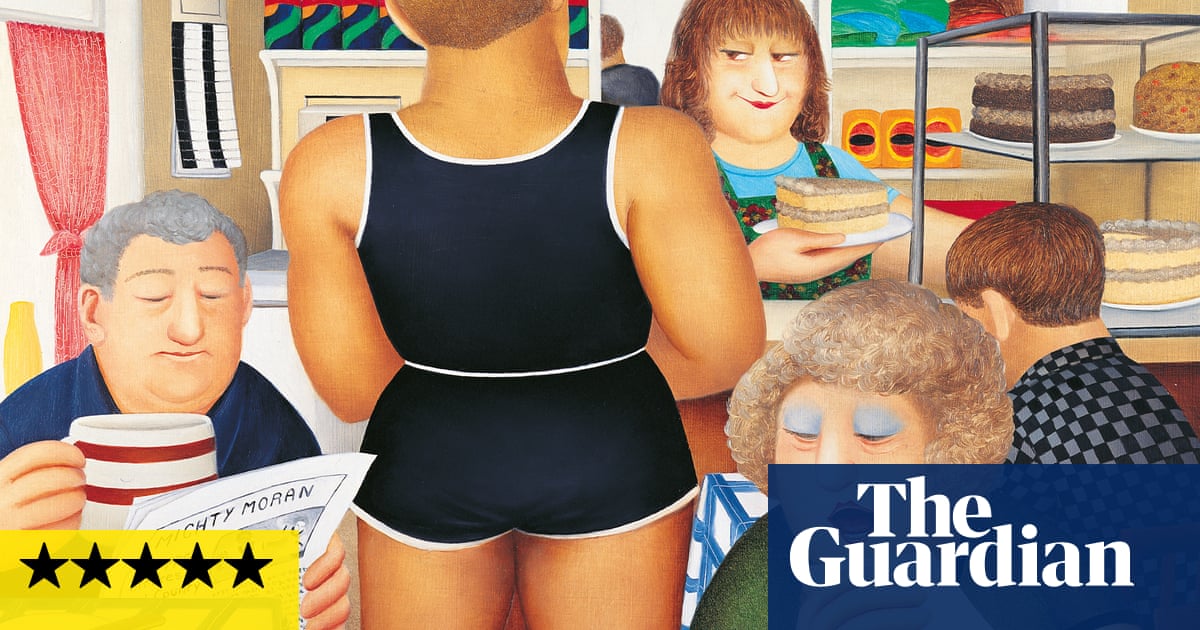

Cook ran a guesthouse on the Hoe, the city’s historic waterfront district, and in the 1970s filled it to bursting with paintings. Her earlier works here are a little timid, uncertain and messy. But by 1974, Beryl is Beryl, assured and confident. All the hallmarks are there: drinking, dancing, dressing up, laughing. Her characters are all big and plump, their bosoms are bursting, their eyes are cartoonish dots, their noses are sausage-y blobs. They all look the same, their uniformity – each figure distinguished only by hairdo or outfit – gives them a sort of universality, an immediate recognisability.

Sailors and Seagulls by Beryl Cook. Photograph: John Cook/Beryl Cook

In 1975, an antique-dealing friend offered to take some paintings off her hands to free up some space, and before she knew it she’d hit the big time: she got a show at Plymouth Art Centre that same year, then an even bigger one at Whitechapel Gallery in London a year later. Soon her work was on magazine covers. She started doing children’s books and even got an OBE.

The appeal is so obvious. Cook makes life look fun. The famous stuff here is all the bawdy, boozy, knee-slapping and titillation. Revellers fall about while doing karaoke, giggling women tumble out of a pub on a hen-do, girls in miniskirts play pool or piss themselves laughing as a male stripper rips off his jockstrap. This is a world of pints and laughter and dancing; of pubs and gay bars and cabarets; of public spaces where private desires can be lived out.

Things get even saucier. There are two hilarious images of whip-wielding dominatrixes. Then a wall of self-portraits finds Cook indulging her and her husband’s fantasies. They dance naked with their reading glasses on. She smokes in lingerie, twirls pom-poms dressed as a cheerleader.

Earnest and emotional … The Back Bar of the Lockyer Tavern by Beryl Cook. Photograph: Beryl Cook/John Cook

And she’s funny too, really funny. An old couple eat chips in a bus shelter covered in graffiti that says “Nigel is a wanker” and “I shagged a froggy”. In the background of her painting of Plymouth Argyle FC scoring a goal, you can just about see a rival fan strangling an Argyle supporter in among the celebrations. It’s great, hilarious, ridiculous.

There’s the basic everyday stuff, too: bingo halls, Dyno-Rod workers clearing a drain, cheeky sailors having a smoke, women shopping at the market, nurses pulling a gurney, and everyone’s smiling and smirking in every painting.

The rest of the show looks at her inspirations (Bruegel and Rubens, apparently) and her experiments with sculpture (including some very snazzy painted loo seats). But the real surprise is how earnest and emotional some of the work here is. Cook paints her son and husband felting a shed roof, her granddaughter on the swing, her daughter-in-law bringing up mugs of tea, everyone smiling gently. It’s so full of actual, genuine love. And it happens over and over in intimate paintings of her family. It’s lovely without being saccharine and gross.

Ordinary is extraordinary … Window Dresser 2 by Beryl Cook. Photograph: Beryl Cook/John Cook

Across town, a companion exhibition at Karst gallery features work by contemporary artists with some thematic or aesthetic link to Cook: the brilliant, satirical cartoons of Olivia Sterling; the hyper-precise celebrations of LGBTQ lives of Flo Brooks; the hypnotic rave minimalism of Rhys Coren. It’s great, clever, fun and more than worth the trip.

Cook’s body-positive depictions of everyday England allowed people to see their lives – whether sailors or strippers, gay or straight – reflected in art. While every serious artist in the country was trying to document the bleakness of working-class English life, Cook was out there saying: “Cheer up, mate, have a pint!”

Her whole point isn’t just that the ordinary can be extraordinary. It’s that the ordinary is extraordinary; that life is amazing, full of laughter and joy and fun. Being alive is precious and fantastical – and we should spend every possible second celebrating it.

Beryl Cook: Pride and Joy is at the Box, Plymouth until 31 May.