We know what will happen to the Sun and our Solar System because we can look outward into the galaxy and examine older Sun-like stars in their evolutionary end states. Nothing lasts forever, including a star’s hydrogen. Eventually, stars deplete their hydrogen fuel and leave the main sequence behind. Stars with masses similar to the Sun will first swell and turn red, then shed their outer layers. That’s what we see when we gaze at older Sun-like stars.

But the fun doesn’t end there.

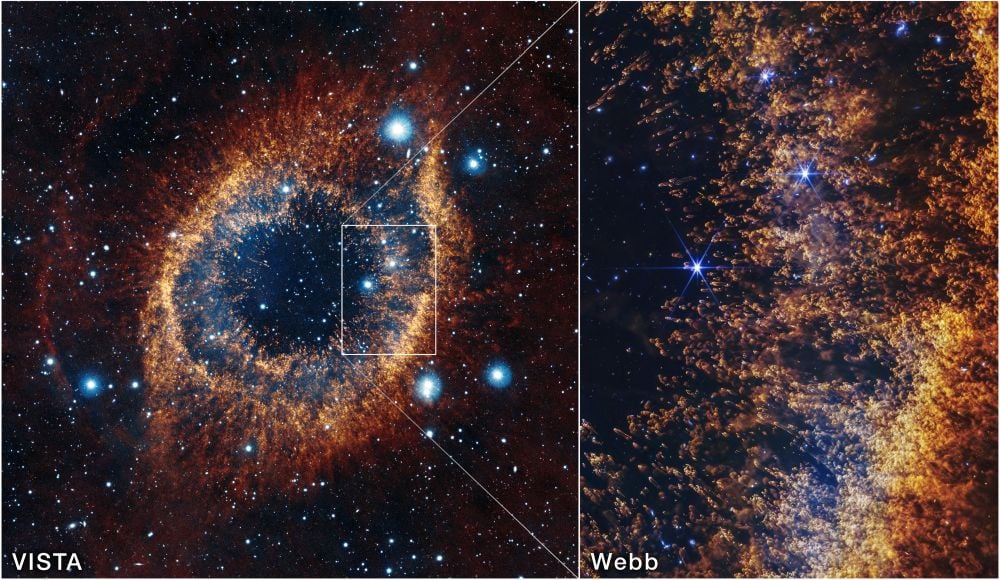

The once-great star then illuminates these gases and ionizes them, creating one of Nature’s most beautiful displays: a planetary nebula (PN). The Helix Nebula is beloved among amateur astronomers and astrophotographers because it looks like a giant eye, so much so that it’s sometimes playfully called the “Eye of Sauron.” Helix also shimmers with vivid colours, like a cosmic jewel suspended in space.

The Helix Nebula is one of the closest bright PN to Earth. It’s around 650 light-years from Earth in the constellation Aquarius. Many Universe Today readers will know it from the Hubble’s well-known portrait of the stunning nebula. A volunteer team of astronomers called the Hubble Helix Team are responsible for the image. They organized a nine-orbit campaign to capture the iconic image.

This is a well-known Hubble image of the Helix Nebula. It’s a composite image of multiple ultra-sharp images of the nebula, though the Hubble did have some help from the Mosaic Camera on the National Science Foundation’s 0.9-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory. The fact that a volunteer group of astronomers called the Hubble Helix Team organized a nine-orbit campaign to image the nebula with the Hubble illustrates the hold that Helix has over people. Image Credit: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner (STScI), and T.A. Rector (NRAO).

This is a well-known Hubble image of the Helix Nebula. It’s a composite image of multiple ultra-sharp images of the nebula, though the Hubble did have some help from the Mosaic Camera on the National Science Foundation’s 0.9-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory. The fact that a volunteer group of astronomers called the Hubble Helix Team organized a nine-orbit campaign to image the nebula with the Hubble illustrates the hold that Helix has over people. Image Credit: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner (STScI), and T.A. Rector (NRAO).

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has also imaged the famous nebula. Its infrared portrait of the Helix Nebula isn’t as widely known as the Hubble’s, but is still noteworthy.

*This infrared false-colour image of the Helix Nebula comes from the Spitzer Space Telescope. The white dwarf at the heart of the nebula appears red in this image, suggesting a malevolent eye. Image Credit: By NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Ariz. – NASA – Comets Kick up Dust in Helix Nebula, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1669175*

*This infrared false-colour image of the Helix Nebula comes from the Spitzer Space Telescope. The white dwarf at the heart of the nebula appears red in this image, suggesting a malevolent eye. Image Credit: By NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Ariz. – NASA – Comets Kick up Dust in Helix Nebula, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1669175*

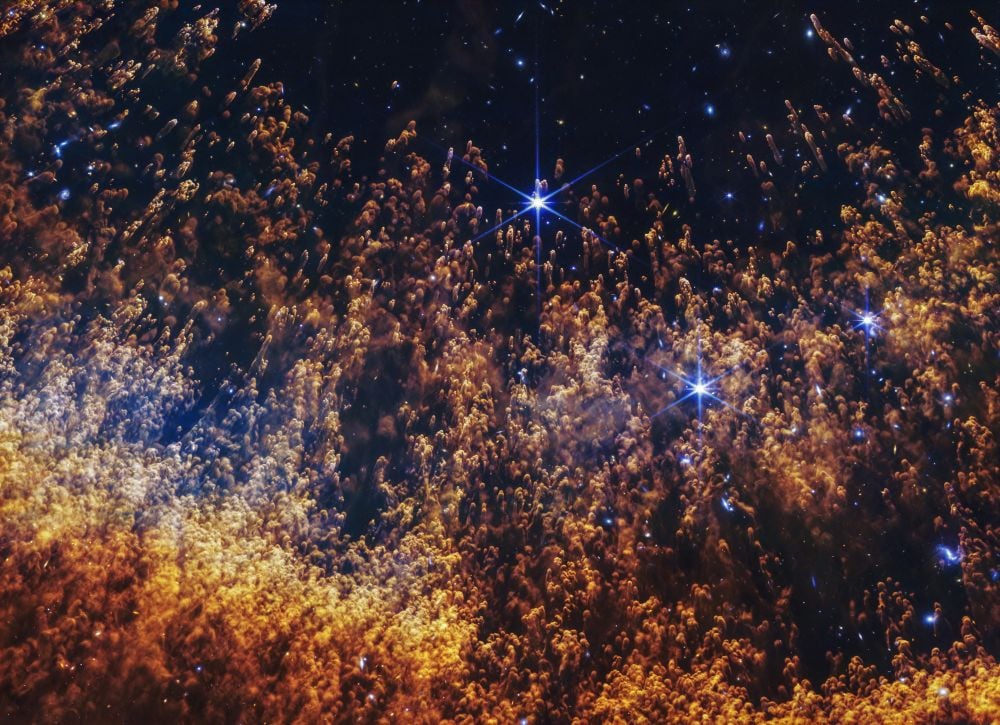

But as we know, there’s a new sheriff in town: the James Webb Space Telescope. We waited with great anticipation for the JWST to finally come to fruition. Not only because of the cosmic knowledge it’s delivering, but because we love pictures of beautiful stellar objects. While the Hubble’s image of the Helix Nebula will always have a place in our star-gazing hearts, the JWST has drawn us even deeper into one of our favourite planetary nebulae.

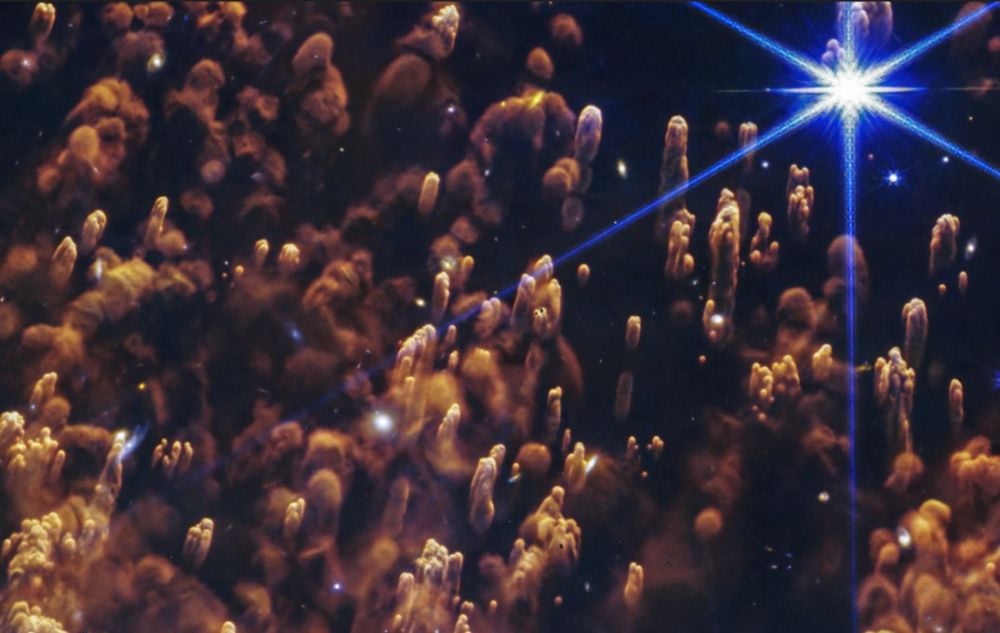

Powerful stellar wind and radiation from the dying star are blowing away the surrounding gas from the star’s expelled outer layers. But there are denser knots of material among the gas, and they’re resisting the onslaught. They’re sometimes called globules, and even cometary knots, because they look like comets leaving dust and vapour trails as they travel through space. We can only see them in the closest PNe, but astronomers think they’re a common feature.

The JWST image is more than just stunning. Each colour in the image tells us something about the nebula. Blue is the hottest gas, which is most energized by the UV radiation coming from the remnant white dwarf star at the nebula’s center. In the bluish regions the hydrogen is atomic. But further out things cool down. The yellow regions is where the hydrogen atoms have combined into molecules (H2) in the cooler temperatures. Even further out in the reddish regions, things are even cooler and dust is forming.

This stunning JWST image shows a small portion of the Helix Nebula. It’s about one light-year across. It’s a composite of separate exposures acquired by the James Webb Space Telescope using its NIRCam instrument. Different wavelength filters were used and separate colours applied were applied to each filtered exposure. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

This stunning JWST image shows a small portion of the Helix Nebula. It’s about one light-year across. It’s a composite of separate exposures acquired by the James Webb Space Telescope using its NIRCam instrument. Different wavelength filters were used and separate colours applied were applied to each filtered exposure. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

The Helix Nebula features around 40,000 cometary knots. The crazy thing is, each one is probably larger than our Solar System, when measured out to Pluto’s orbit. Of course, they’re nowhere near as massive. The head of each knot is well-illuminated and ionized by the nebula’s star, while a tail of less well-energized gas trails behind them.

This zoomed-in image highlights cometary knots in the Helix Nebula. Each of the knots is likely larger than the Solar System. A foreground star with diffraction spikes is prominent, and stars and distant galaxies are hiding in the background. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

This zoomed-in image highlights cometary knots in the Helix Nebula. Each of the knots is likely larger than the Solar System. A foreground star with diffraction spikes is prominent, and stars and distant galaxies are hiding in the background. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Research has shown that the Helix Nebula is the result of three separate pulses, or three separate epochs of mass-loss, as researchers explained. Those epochs conform to the inner disk, the outer ring, and the outermost ring. The outermost rings shows how expelled mass gas has interacted with the interstellar medium. It contains numerous features that appear to be shocks, and its upper-right segment seems to be flattened by interactions with denser gas.

In astronomical terms, planetary nebulae like the Helix Nebula don’t last long. It’s about 10,000 to 12,000 years old, which is kind of old for a planetary nebula. Its progenitor star started shedding its outer layers between about 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. For the next 10,000, maybe 20,000 years, Helix will continue to expand. Its gas will thin out, and as the white dwarf cools, less radiation will light the gases up. It will grow dimmer and fainter, and will cease to be. Somewhere around 50,000 years after its formation, it will be dispersed into and become part of the interstellar medium.

This is our Sun’s final fate. As it nears the end of its life on the main sequence, it will expand into a red giant. The once-yellow Sun, which will have turned a glowering red, will not be able to maintain its gravitational hold on its gaseous outer layers. They’ll be shed into space, then lit up by the long-lived remnant of the Sun, a white dwarf. The white dwarf will be a fading stellar cinder, emanating only remnant heat for billions of years.

The nebula and its colours represent a dying star’s final gasp, a stellar exhalation that spreads star-stuff out into the cosmos. The material could be taken up in the next round of star formation. Some of this material may even become part of a planet or planets in the future. Maybe one of them will be rocky, with liquid water. Perhaps sometime in the future, some of this water will sit in a warm little pond on the surface of this new world. It’ll be a primordial soup rich with prebiotic chemistry, bathed in UV light by its star…