North Carolina State University scientists have created a futuristic material that heals itself over 1,000 times, which could lead to cars, aircraft, wind turbines, and spacecraft lasting for centuries without costly maintenance and repair.

Although the new material, which is stronger than composites currently used for such applications, is still in the testing phase, the researchers behind its creation are already working with industry partners to bring their self-healing composite to the marketplace.

“This would significantly drive down costs and labor associated with replacing damaged composite components, and reduce the amount of energy consumed and waste produced by many industrial sectors – because they’ll have fewer broken parts to manually inspect, repair or throw away,” explained Jason Patrick, corresponding author of the paper and an associate professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at North Carolina State University.

Weakness in Current FRBs Motivated Futuristic Material That Heals Itself

When engineers want strong, lightweight materials that can withstand extreme pressures, they increasingly turn to fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites. Made from layers of fibers, such as carbon fiber or glass, bonded together by a polymer matrix, such as epoxy, FRBs are often the go-to material for aircraft, spacecraft, automobiles, and wind turbines due to their impressive strength-to-weight ratio.

While this advanced material is also beginning to appear in other modern structures, its widespread use has revealed an inherent problem that leads to its breakdown: interlaminar delamination. Specifically, FRBs develop small cracks under pressure that can cause the fiber layers to separate from the bonding matrix.

“Delamination has been a challenge for FRP composites since the 1930s,” Professor Patrick explained.

Tests Prove Material’s Resilience After 1,000 Repeated Fractures

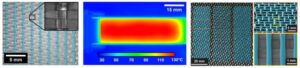

To create an FRB capable of repeatedly healing itself, the NC State research team 3D printed a thermoplastic healing agent onto the base fiber reinforcement. This material combination formed a polymer-patterned interlayer that helps resist delamination.

Next, the researchers embedded a thin carbon-based layer into the composite material, which heats up when an electrical current is applied. When the team tested this layer by applying a current, the healing agent melted, allowing it to flow into cracks and microfractures within the FRB caused by repeated stress. According to the research team, this process “re-bonds” the delaminated layers, restoring the FRB’s structural integrity.

This image shows: (left) 3D printed thermoplastic healing agent (blue overlay) on glass-fiber reinforcement; (middle) infrared thermograph during in situ self-healing of a fractured fiber-composite; (right) 3D printed healing agent (blue) on carbon-fiber reinforcement. Image Credit: Jason Patrick, NC State University.

This image shows: (left) 3D printed thermoplastic healing agent (blue overlay) on glass-fiber reinforcement; (middle) infrared thermograph during in situ self-healing of a fractured fiber-composite; (right) 3D printed healing agent (blue) on carbon-fiber reinforcement. Image Credit: Jason Patrick, NC State University.

After constructing an automated testing system designed to repeatedly apply a tensile force to their new FRB, they tested the material’s resilience by triggering a 50-millimeter-long delamination and then applying a current to activate the material’s self-healing process. Over the next 40 days, the team triggered 1,000 cycles of fracturing and healing while measuring the material’s resistance to delamination between each cycle.

According to Jack Turicek, the study’s lead author and a graduate student at NC State, these tests revealed two key findings. First, the fracture resistance of their futuristic material that heals itself started out “well above” that of unmodified FRBs.

“Because our composite starts off significantly tougher than conventional composites, this self-healing material resists cracking better than the laminated composites currently out there for at least 500 cycles,” Turicek explained.

When evaluating the material’s resistance over the entire 1,000 test cycles, the researchers found it lost some of its resistance as the same area was repeatedly cracked and healed. However, Turicek noted, the futuristic material that heals itself loses this ability “very slowly.”

Building Aircraft and Spacecraft that Could Last for Centuries

When discussing possible commercial and industrial applications, Professor Patrick said large, expensive-to-maintain aircraft and wind turbines would be ideal candidates. However, the researcher also noted the potential benefits for spacecraft operating in “largely inaccessible environments” where conventional on-site repair techniques are not an option.

In terrestrial applications like wind turbines or aircraft, the team estimates their futuristic material that heals itself would be triggered by actual events like bird strikes or could be intentionally activated during scheduled maintenance. Depending on the number of events and the frequency of intentionally activated self-repair, the material could last for decades or even centuries beyond currently available FRBs.

“We believe the self-healing technology that we’ve developed could be a long-term solution for delamination, allowing components to last for centuries,” Professor Patric explained. “That’s far beyond the typical lifespan of conventional FRP composites, which ranges from 15-40 years.”

Although the futuristic material that heals itself is not yet commercially available, the professor has founded his own company called Structeryx and already patented the technology. His next step is to license the approach to manufacturers.

“We’re excited to work with industry and government partners to explore how this self-healing approach could be incorporated into their technologies, which have been strategically designed to integrate with existing composite manufacturing processes,” Patrick said.

The study “Self-healing for the Long Haul: In situ Automation Delivers Century-scale Fracture Recovery in Structural Composites” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Christopher Plain is a Science Fiction and Fantasy novelist and Head Science Writer at The Debrief. Follow and connect with him on X, learn about his books at plainfiction.com, or email him directly at christopher@thedebrief.org.