For Deirdre Barker, the penny dropped as regards what her husband Ed was experiencing while reading an article in late 2020 about the death and postmortem diagnosis of the US actor and comedian Robin Williams.

She made some notes and at the next meeting with Ed’s consultant said: “I think my husband has Lewy body dementia.”

He nodded and sat there silently for a while before Ed pressed him, asking: “Well, what do you think about that?”

“I think your wife is a very smart woman,” he replied.

Ed died in early 2024 in a nursing home in Wexford at the age of 76 following an accelerated decline from Lewy body dementia (LBD) – often referred to as the most common form of dementia that you’ve likely never heard of.

The conversation described above occurred three years after Ed first sought medical advice about a tremor he was experiencing. The couple’s GP suspected Parkinson’s, but there was an 18-month waiting list to see a specialist. When Ed started showing other symptoms – including mild cognitive decline, problems with spatial awareness, the flipping of his body clock, and suicidal thoughts – they decided to go private.

The consultant confirmed their GP’s suspicions: Parkinson’s disease.

Current estimates suggest that 10,000-12,000 people in Ireland are living with LBD, with only a small percentage ever receiving an accurate diagnosis. To help change this, Emerald-Lewy, a multi-site, multi-stakeholder research programme dedicated to improving the diagnosis, management and lived experience of Lewy body dementia in Ireland, has been established. It is led by Prof Iracema Leroi, geriatric psychiatrist at the Mercer’s Institute for Successful Ageing at St James’s Hospital in Dublin and site director of the Global Brain Health Institute in Trinity College Dublin, with funding support from the Health Research Board.

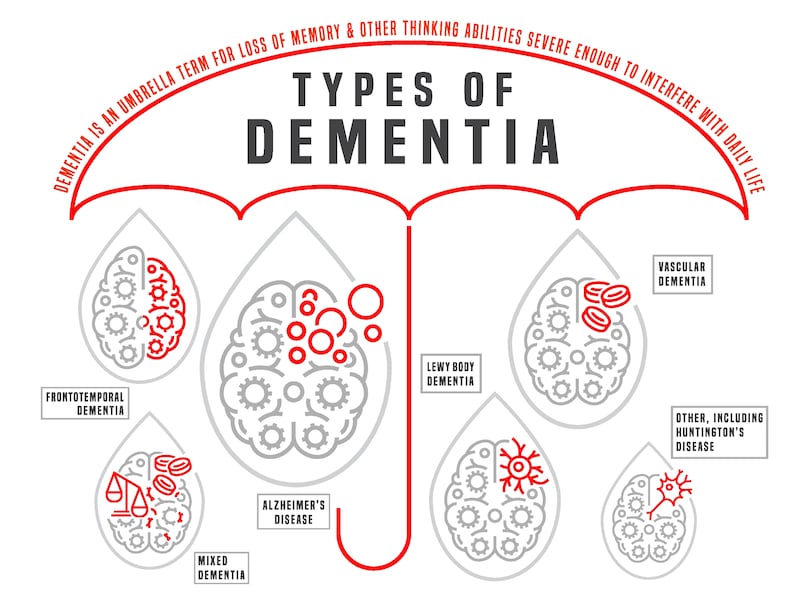

Types of dementia: ‘From a pathological perspective, LBD and Parkinson’s are opposite sides of the same coin. But the symptoms and the experience that patients can have at an individual level vary hugely’

Types of dementia: ‘From a pathological perspective, LBD and Parkinson’s are opposite sides of the same coin. But the symptoms and the experience that patients can have at an individual level vary hugely’

Seán O’Dowd, a consultant neurologist and clinical lead at Ireland’s National Dementia Services, is part of the Emerald-Lewy team. It isn’t the first time he’s been involved in a project to develop practical tools to help clinicians better identify and manage LBD. More than 10 years ago, while in Newcastle upon Tyne (one of the world’s leading centres of research into the condition), he contributed to the early iterations and validation of Diamond Lewy, a diagnostic and management toolkit that is now freely available for clinicians and researchers to download. It is widely used across the UK and increasingly in the Republic.

“That toolkit was designed to identify some of the features that are likely to make LBD the correct, specific diagnosis,” he explains. “Some of them may not be necessarily high on the radar of things you might ask in a memory clinic as a lot of the approach is understandably focused around typical Alzheimer’s disease [the most common form of dementia] and the difficulties that group of patients have.

“Lewy body disease has a different set of cognitive difficulties and there is a suite of other potential symptoms – from the perspective of movement problems, sleep difficulties, visual hallucinations, regulation of the autonomic nervous system like bladder, bowel, blood-pressure control, and so on.”

Lewy bodies are abnormal clumps of protein that build up inside brain nerve cells, disrupting their function and eventually causing them to die.

When it comes to the differentiation in diagnosis between LBD and Parkinson’s disease, Dr O’Dowd describes them as either side of the same coin.

“Lewy body disease is a pathological umbrella term which describes the changes we see in the brains of people [in postmortem analysis] who have lived with Parkinson’s disease or indeed with dementia with Lewy bodies.

“From a pathological perspective, these two diseases are opposite sides of the same coin. But the symptoms and the experience that patients can have at an individual level vary hugely. People with Parkinson’s disease have a movement-dominant syndrome with sometimes little or no cognitive involvement at all – or, when it does come, it’s several years into the diagnosis.

I know now I was exhausted. When Ed was finally admitted to a nursing home in Wexford he was placed immediately into the highest level of care available. I was delivering that at home

— Deirdre Barker

“Whereas people with dementia with Lewy bodies present with and manifest cognitive symptoms very early as a leading feature or rapidly after developing a Parkinson-type movement disorder … within a year or so is the rule that we would use clinically.”

To help the medical sector and members of the public to better understand these nuances, Emerald Lewy is hosting an awareness and engagement event in Dublin on World Lewy Body Dementia Day, January 28th. The event- at Unit 18, Trinity College Dublin, East Campus, D2, 8QR5+VH – is free and open to the public and those in the medical profession from 3.30pm. There are special slots for schools from noon-2pm and a dementia-friendly slot from 2.30pm-3.30pm. (Contact: brownesh@tcd.ie for more information).

Eben Stewart and his wive Sandrine, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2017 at age 45

Eben Stewart and his wive Sandrine, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2017 at age 45

Eben Stewart, who was primary carer for his French-born wife Sandrine for five years, joined Emerald-Lewy to raise aware of LBD for both those living with the condition and those thrust into a carer role. Sandrine was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2017, when she was 45. Their three sons were aged between 12 and 18 at the time.

“We lived with that diagnosis and treatment for two years, coming to terms with it,” Eben explains. But soon after the diagnosis they started noticing other issues.

A homemaker renowned for her multitasking and project planning, Sandrine became unable to prepare her celebrated, elaborate lunches and dinners, and started to struggle to understand the timing and sequencing of her Parkinson’s medication. They knew there was more going on when the hallucinations started.

Sandrine and Eben Stewart. Sandrine is in full-time care

Sandrine and Eben Stewart. Sandrine is in full-time care

“They started with shadows – if there was a coat hanging, for instance, she’d think there was someone there. During Covid it developed where she was seeing animals running through the house. Then she’d be talking to children and she’d be engaging with them. But then they started to become more sinister … threatening,” Eben recalls.

Sandrine’s early-onset form of LBD is genetic, and prompted a relatively rapid decline. Approximately 1 per cent of dementias are directly caused by a specific gene mutation, known as familial dementia, and they often appear before age 65 – the cut-off age before which onset is called young or early dementia.

[ Study finds link between eating cheese and lower dementia riskOpens in new window ]

Eben was still teaching full time and soon he was burnt out managing Sandrine’s increasing care needs as well as the demands of three active teenage boys. On the advice of her medical team, Sandrine was hospitalised in St James’s for a month in December 2022 to offer some respite, but due to her deteriorating condition was moved from there on to Bloomfield Hospital where she remains in full-time care. She is in the final stages of the disease and, although awake and alert, cannot communicate coherently.

“My mum has late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. I was visiting her yesterday, and she doesn’t know me,” says Eben, when we speak in the Global Brain Health Institute at TCD. “Then I visit Sandrine, and she’ll always know me. I hope.”

Deirdre recalls how she started to become more watchful and concerned about Ed as his symptoms progressed, a stage she now recognises as the start of her caring role.

“It starts very slowly and just creeps up and you don’t even know it’s happening. I felt quite disturbed and resentful about the impact it had on my life,” she acknowledges.

“I have to be really honest about that. I really struggled. I remember thinking, ‘Ed has a diagnosis. I don’t have a diagnosis. How come this is making such an impact?’ Looking back, I know now I was exhausted. When Ed was finally admitted to a nursing home in Wexford he was placed immediately into the highest level of care available. I was delivering that at home.”

‘I can’t switch the film off in my head.’ Deirdre Barker and her husband Ed

‘I can’t switch the film off in my head.’ Deirdre Barker and her husband Ed

According to research undertaken by the Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland (ASI), more than 180,000 people in the Republic are or have been carers for a family member or partner with dementia, with many more providing support and care in other ways. In its2022 pre-budget submission the ASI estimated the value of this work to the State to be in the region of €804 million annually. There are approximately 64,000 people living with dementia in the State, which is expected to double to 150,000 by 2045 as the population ages.

When Ed eventually transitioned into the nursing home, his hallucinations, which previously had been benign, became invasive and frightening.

“He asked one of the male carers if he would help him take his own life,” Deirdre recalls. “He told him: ‘I can’t switch the film off in my head.’ He was terrified.”

Appropriate medication eventually helped with his hallucinations.

It was a cruel irony that one of Ed’s last artistic outputs with his wife was a documentary film they made with Wexford film-maker Philip Bertrand Cullen called Buttons, Zips, and Belt Buckles capturing their navigation of the myriad symptoms of LBD, among them a loss of dexterity and executive function essential for planning and co-ordinating activities, including the capacity to dress oneself.

Nonetheless, Deirdre takes comfort from the fact that Ed knew her to the end.

“When I talk about Ed people ask: ‘Did he know you at the end?’ What he had didn’t affect his character, his temperament or his knowledge of who we were. Looking back, that’s a huge blessing,” she says.