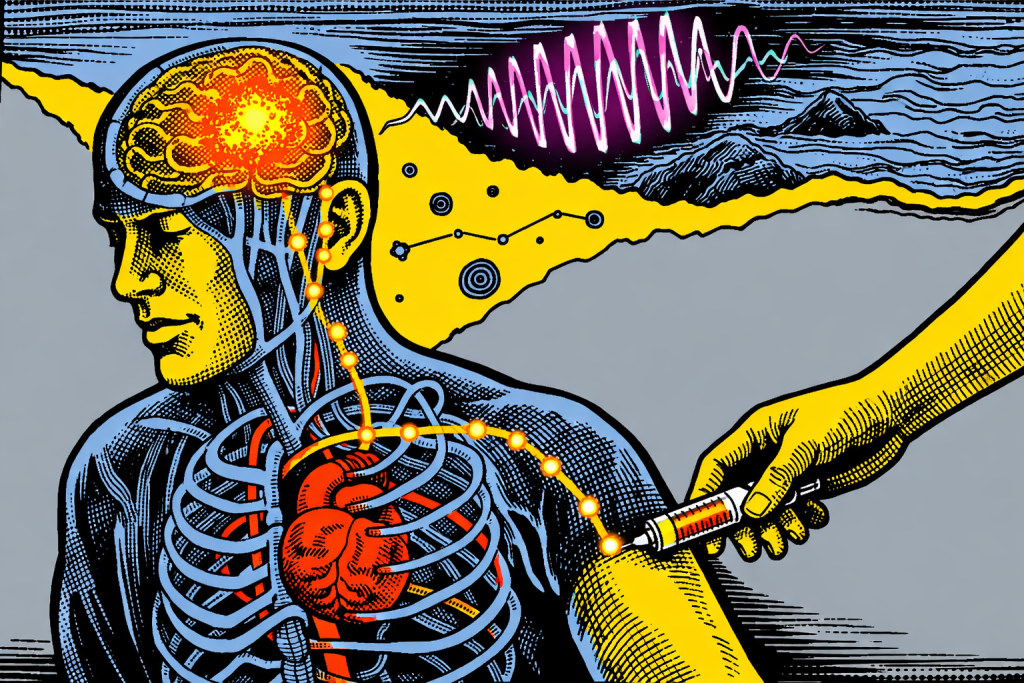

Tiny wireless chips injected through the bloodstream could reshape how we treat brain disease and how long we stay well.

The idea of a brain implant immediately brings up a specific image of an operating room, a shaved head, surgeons navigating millimeters of tissue with extreme caution. It is life-saving for some, but it is also invasive, costly and usually reserved for when disease has already taken a serious toll.

Now, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) are now challenging that assumption. What if placing a brain implant didn’t require opening the skull at all? What if it looked more like getting an IV injection in the arm?

That question is no longer hypothetical. In research published in Nature Biotechnology, scientists at MIT demonstrated a way to deliver microscopic, wireless brain implants through the bloodstream. No surgery required.

How a brain implant can travel like a cell

The breakthrough lies not just in shrinking electronics, but in how they move through the body. Instead of surgically implanting devices into the brain, the researchers fused tiny electronic chips with living immune cells before injection [1].

Think of it as hitching a ride. Immune cells already know how to travel through blood vessels, slip into inflamed tissue, and cross the brain’s protective border, the blood-brain barrier, without damaging it. By attaching electronics to these cells, the researchers let biology do what it does best: navigate the body safely and efficiently.

Once injected into a vein, these cell–electronics hybrids circulate naturally. In mouse studies, they autonomously traveled to targeted brain regions affected by inflammation, settled near neurons and stayed put without harming surrounding brain tissue [1].

Traditional brain implants rely on electrodes that stimulate relatively large areas. By comparison, these new devices are astonishingly small, about one-billionth the length of a grain of rice. That scale matters.

Their size allows them to nestle among neurons rather than push tissue aside. Imagine replacing a fence post with grains of sand that arrange themselves exactly where needed. The result is far more precise neuromodulation, with electrical stimulation delivered only where it’s required.

In experiments, the implants stimulated brain regions with an accuracy of about 30 microns. Importantly, they did this without disrupting movement, cognition or nearby neural activity.

Once in place, the implants don’t rely on batteries or wires. Instead, they are powered wirelessly using near-infrared light delivered from outside the body. That light activates the devices, allowing clinicians to modulate neural activity on demand.

This is the same underlying principle used in existing neuromodulation therapies for conditions like Parkinson’s disease or epilepsy, but without drilling into the skull, implanting leads or managing surgical recovery.

Why this matters for disease and for aging

Neuromodulation has shown promise for treating brain tumors, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic pain and other neurological disorders. The challenge has always been access. Surgery raises risks and costs, and it often delays intervention until the disease is advanced.

By eliminating surgery, this approach could move treatment earlier, when it has a better chance of preserving function rather than compensating for loss.

That shift is especially important in the context of longevity. Many brain diseases develop slowly over years or decades. Earlier, gentler intervention could help maintain cognitive health longer, not just extend lifespan.

“While brain implants usually require hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical costs and risky surgical procedures, circulatronics technology holds the potential to make therapeutic brain implants accessible to all by eliminating the need for surgery,” says Deblina Sarkar, senior author of the study and head of MIT’s Nano-Cybernetic Biotrek Lab [2].

A platform, not a single solution

The team calls the technology circulatronics and sees it as a platform rather than a one-off device. In this study, they targeted brain inflammation using immune cells called monocytes. In the future, different cell types could be used to reach tumors, pain pathways, or disease-specific brain regions.

Because the implants are delivered through the bloodstream, they may also be suited to conditions like glioblastoma, where tumors appear in multiple locations that are difficult or impossible to reach surgically.

“This is a platform technology and may be employed to treat multiple brain diseases and mental illnesses,” Sarkar says. “Also, this technology is not just confined to the brain but could also be extended to other parts of the body in future [2].”

Still early, but directionally important

The researchers are clear-eyed about the timeline. This is early-stage work, demonstrated in animal models. Long-term safety, control and stability will determine whether it succeeds in humans. The team aims to move toward clinical trials within three years through a newly launched startup, Cahira Technologies.

Even so, the implications are hard to ignore. If devices like these translate clinically, they won’t just improve brain care; they could redefine what “invasive” medicine means.

For longevity science, this matters because extending healthy life is not only about breakthrough therapies, but about reducing the physical cost of receiving them. Technologies that work with the body, rather than cutting into it, point toward a future where treating disease no longer accelerates decline.

A brain implant delivered by injection may sound radical today. But if this work continues to progress, the most transformative medical tools of the future may arrive quietly through the bloodstream rather than the operating room.

[1] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02809-3

[2] https://news.mit.edu/2025/new-therapeutic-brain-implants-defy-surgery-need-1105