If you have ever watched a bat cut through the night sky, it almost feels unreal. No light, no landmarks, yet no crashes either. They twist through branches, slip past leaves, and chase insects at high speed, all in pitch black darkness.

For decades, scientists have known bats use echolocation. They send out high-pitched calls and listen for the echoes that bounce back. But one big question never quite went away.

How do they make sense of all that noise?

Because in a forest or hedgerow, a single bat call doesn’t return one neat echo. It comes back as thousands. Every leaf, twig, and branch reflects sound. It’s like shouting into a crowded cave and somehow being able to tell where every wall is.

Now, a new study led by researchers at the University of Bristol has uncovered the trick. Bats don’t try to track every echo. They listen to how the whole soundscape flows around them.

The research, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, shows that wild bats use something called acoustic flow to control their flight. It works a lot like how humans judge motion with their eyes, except bats do it with sound.

Think about riding a bicycle. When you speed up, the scenery seems to rush past you faster. When you slow down, it drifts more gently. Your brain uses that visual “flow” to judge how fast you are moving, even without looking at a speedometer. Bats do the same thing. But with echoes.

As a bat flies and sends out a call, the returning echoes shift in pitch slightly depending on how fast the bat is moving and how close objects are. This tiny change is called a Doppler shift. The faster the bat moves, the more those echoes change. That shifting sound creates a kind of acoustic motion picture of the world. And the bat reads it.

To prove this, the researchers did something wonderfully strange. They built what they called a Bat Accelerator Machine.

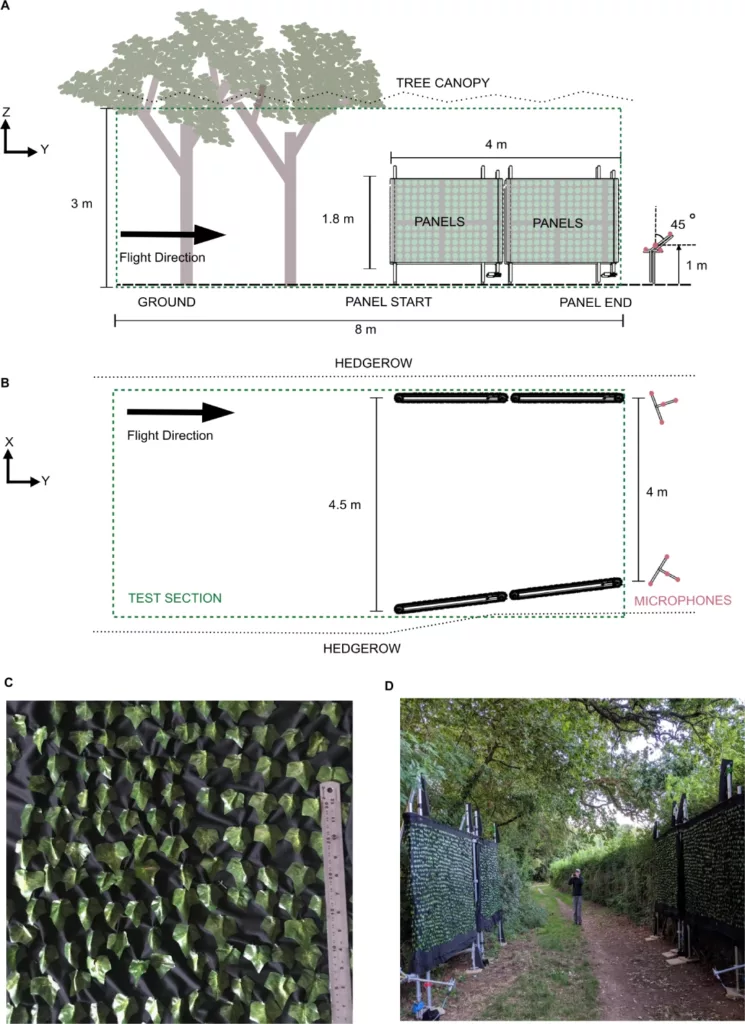

It was an eight-metre-long flight corridor lined with thousands of artificial leaves. These leaves were attached to rotating panels that could move either in the same direction as a flying bat… or against it. To a bat, this would make echoes feel as if the world were moving faster or slower than it really is.

Researchers explore the evolutionary transition from gliding to powered flight in Bats.

Over three nights in the UK countryside, the team recorded 181 flights of wild pipistrelle bats. Of those, 104 bats flew all the way through the experimental corridor and gave usable data.

Credit: Proc Biol Sci (2026) 293 (2063): 20252481

And the bats behaved exactly as the acoustic-flow idea predicted.

When the panels moved against the bat’s direction of flight, the echoes came back with stronger Doppler shifts. To the bat, it felt like it was going faster than it really was. So it slowed down… by as much as 28 percent.

When the panels moved with the bat, the Doppler shifts were weaker. The bat felt like it was moving too slowly. So it sped up.

No vision, no tracking of individual leaves. Just listening to the changing music of echoes.

Dr Athia Haron, the study’s lead author, explains it simply. In complex environments, trying to analyse every single echo would be impossible. There are just too many. So bats use a shortcut. They read the overall pattern of sound moving around them.

Professor Marc Holderied adds that this flow of sound tells bats both how fast they are moving and how close they are to obstacles. It’s an elegant solution to a very messy sensory problem. And it makes sense.

In a thick hedge, echoes from hundreds of leaves overlap. Tracking one leaf from one call to the next would be like trying to follow a single raindrop in a storm. But Doppler shifts don’t care which leaf the echo came from. They only care about motion. That makes them perfect for navigation.

This discovery also has a surprising side effect. It could change how we design drones.

Deep sea fish can see color in darkness

Right now, most drones and autonomous vehicles rely on cameras, GPS, or heavy computing to navigate. But bats do something much more efficient. They estimate their motion just from changes in sound. That idea, using Doppler-based acoustic flow, could inspire new navigation systems that work in fog, darkness, smoke, or cluttered environments where cameras struggle.

Dr Shane Windsor, one of the co-authors, joked that they managed to make bats fly even faster using their corridor of revolving hedges. But behind the humour is a serious result. The experiment showed that bats really are tuning into these Doppler shifts to control their speed.

So the next time you see a bat zig-zagging through the twilight, remember this.

It isn’t guessing, reacting at random. It is reading an invisible river of sound and surfing it through the dark.

Journal Reference

Athia H. Haron, Marc Wilhelm Holderied, Shane Windsor; Acoustic flow velocity manipulations affect the flight velocity of free-ranging pipistrelle bats. Proc Biol Sci 1 January 2026; 293 (2063): 20252481. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.2481