Initial analyses suggested if the dots were in fact supermassive black holes, they’d have to be nearly as massive as their host galaxies, varying between 10 and 100 percent of their total mass. The problem was that the dots were visible at very high red shift, which means astronomers saw them as they were when the Universe was roughly 1 billion years old. An “overmassive” black hole as heavy as its entire galaxy in a 1-billion-year-old Universe begged the question how something could grow that big, that fast—we didn’t have any answers for that.

But then Rusakov and his colleagues started noticing odd things in the JWST data. “You normally expect other signals from supermassive black holes, like X-rays, and we didn’t see those signals,” Rusakov says. The oddities didn’t end with the absence of X-rays.

The wide lines

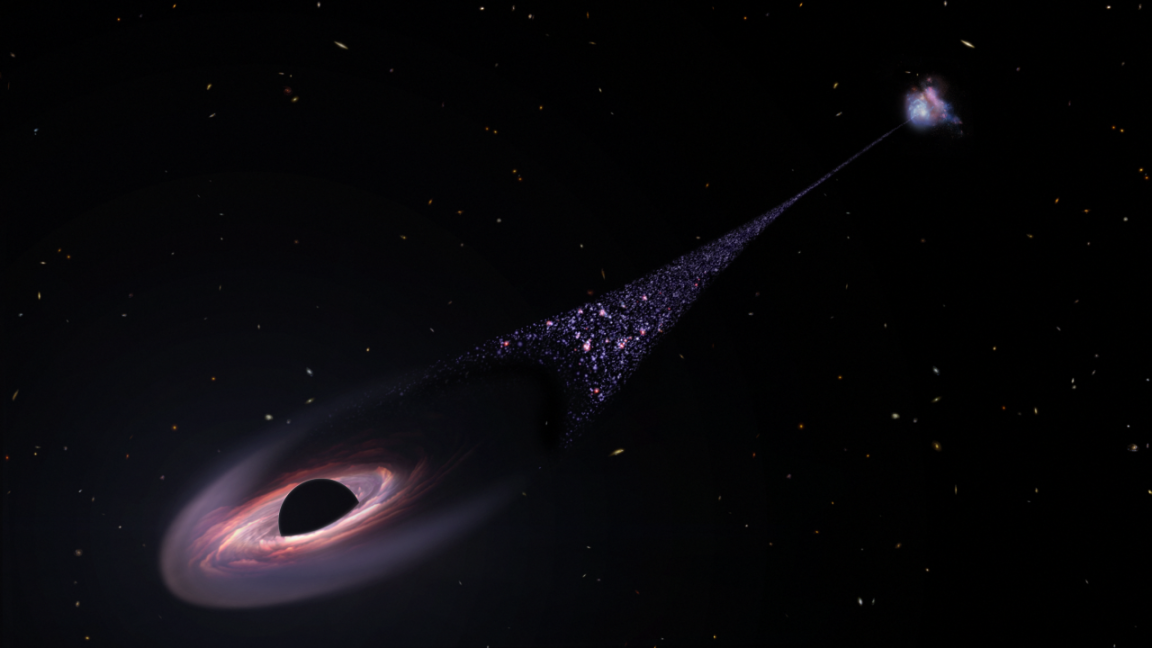

Because black holes can’t be observed directly, astronomers measure their mass by looking at gas orbiting around them. As the gas swirls down into the black hole, it heats up and glows. The gravity of a supermassive black hole pulls that gas at incredible speeds, with the material reaching thousands of kilometers per second. This speed causes what’s known as the Doppler effect, broadening where the light from the gas moving toward the observer on Earth shifts to blue, and the gas moving away shifts to red, stretching the spectral lines into a wide, flat shape. By measuring the width of these lines, we calculate the velocity of the gas and, by extension, the mass of the black hole.

In the case of the Little Red Dots, the lines appeared incredibly wide, leading to those staggering mass estimates. The shape of the lines, though, looked strange. It wasn’t a typical rounded bell-curve but rather a sharp triangle sitting on top of broad, wing-like tails.