On Alaska’s remote cliffs, the summer air once thundered with seabirds returning from the sea. The spectacle drew scientists, wildlife watchers, and fishers alike, all familiar with the rhythmic cycles of the North Pacific. Then the noise began to fade.

By the end of the last decade, field teams working across thousands of kilometers noticed the same unsettling pattern: empty nests, silent ledges, and vanishing murres. In some areas, colonies had simply collapsed. At first, the cause remained unclear. No oil slicks, no industrial accidents, no signs of disease.

A group of common murres on a cliff edge in Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. Credit: Brie Drummond/USFWS

A group of common murres on a cliff edge in Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. Credit: Brie Drummond/USFWS

What emerged instead was something far larger, more elusive, and less visible than a traditional environmental disaster. A subtle, long-duration shift in ocean conditions had rewritten the ecological playbook. Researchers soon realized they were witnessing not a temporary fluctuation, but a full-scale collapse.

Largest Seabird Die-off in Modern History

Between 2015 and 2016, approximately 4 million common murres (Uria aalge) disappeared from breeding sites across Alaska. The cause was linked to a sustained marine heatwave in the North Pacific, a phenomenon scientists labeled “The Blob”. The murre mortality represents the largest documented die-off of a single vertebrate species in modern times, based on a 2024 peer-reviewed study published in Science.

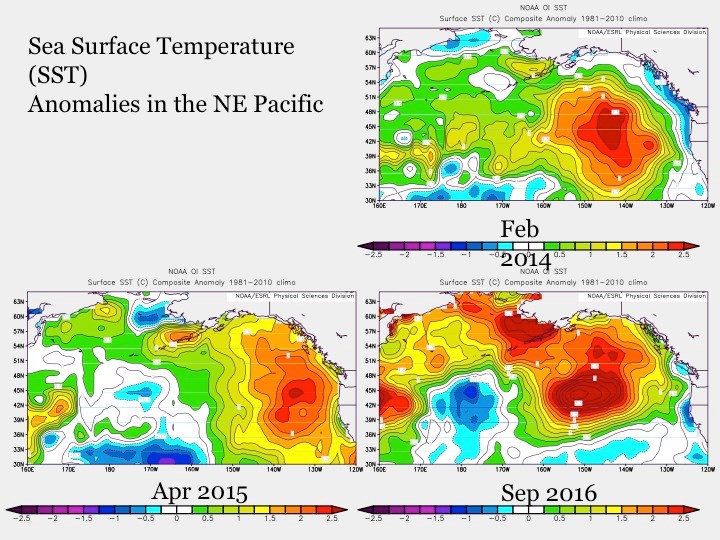

Sea surface temperature departures from normal. In this series of maps from 2014-2016, the Blob appears as a deep red warm spot and shows how it has moved and changed in intensity over time. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/NOAA

Sea surface temperature departures from normal. In this series of maps from 2014-2016, the Blob appears as a deep red warm spot and shows how it has moved and changed in intensity over time. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/NOAA

The heatwave raised ocean surface temperatures by up to 5.5°C in affected areas, disrupting the base of the food web. Forage fish such as capelin and sand lance, essential to murre diets, became scarce. As deep-diving specialists, murres require consistent access to high-energy prey to survive and reproduce. During the heatwave, they could not meet their energy needs.

Extensive carcass surveys and multi-year population data collected across 13 long-term seabird monitoring sites enabled researchers to estimate total losses. Over 62,000 murre carcasses were recorded on beaches, but the vast majority of deaths occurred at sea. Data from 2015 to 2017 confirmed widespread reproductive failure, with 22 monitored colonies showing zero successful breeding.

Common murres washed up on a rocky beach in Prince William Sound during a massive die-off due to a catastrophic marine heatwave in 2015-16. Credit: David Irons

Common murres washed up on a rocky beach in Prince William Sound during a massive die-off due to a catastrophic marine heatwave in 2015-16. Credit: David Irons

The Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge led the long-term seabird observation network, collaborating with the University of Washington, USGS, and other agencies. Breeding colonies that once hosted hundreds of thousands of birds now operate at historically low levels. Through the end of 2025, no recovery trend has been observed at any of the surveyed sites.

Ecological Disruptions Extend Beyond Murres

The murre collapse was only part of a broader set of biological failures during the heatwave. Pacific cod populations crashed by 80%, forcing temporary closures of key Gulf of Alaska fisheries. Other forage species, including juvenile pollock and herring, suffered similar declines. These losses disrupted diets for top predators such as sea lions, whales, and sea otters, and strained subsistence harvests in Alaska Native communities.

Resource managers found no evidence linking the die-off to toxins, disease, or direct human activity. Instead, changes in ocean temperature and circulation likely drove systemic failures. Warmer surface waters limited vertical nutrient mixing, reducing plankton productivity and reshaping food availability across multiple trophic levels.

Comparison of common murre colony on a census plot, South Island, Semidi Islands, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, before and after the 2015-2016 marine heatwave. The top image shows the colony in 2014, and the bottom image shows the colony in 2021. Credit: USFWS

Comparison of common murre colony on a census plot, South Island, Semidi Islands, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, before and after the 2015-2016 marine heatwave. The top image shows the colony in 2014, and the bottom image shows the colony in 2021. Credit: USFWS

Between 2017 and 2018, similar seabird die-offs were reported in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. While smaller in scale, they reflected the same underlying vulnerability. The National Park Service warned that persistent warm anomalies could amplify risks for other cold-adapted marine species. Researchers noted that species like thick-billed murres showed greater resilience, suggesting that ecological thresholds vary by niche and range.

Baseline monitoring across decades revealed that colony fluctuations once considered normal have been replaced by consistent declines across all observed locations. Biologists now believe the region’s carrying capacity for murres may have been permanently altered.

Long-Term Monitoring Uncovers Slow Crisis

The severity of the die-off became evident only through deep, multi-decade monitoring. Without consistent colony counts and breeding records, the scale of the event might have gone unnoticed. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has maintained population surveillance at more than 20 core sites and 10–15 auxiliary locations, some for over 50 years.

Monitoring teams documented not just carcasses, but reproductive behavior, nest success, and chick diet composition. In 2020, preliminary estimates placed the death toll between 500,000 and 1 million birds. Follow-up research expanded the known impact by a factor of four, confirming a total loss of 4 million murres, based on consistent colony collapse across both the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea ecosystems.

Common Murre on the water in the eastern Bering Sea. Credit: Robin Corcoran/USFWS

Common Murre on the water in the eastern Bering Sea. Credit: Robin Corcoran/USFWS

The findings, published in Science, are detailed in the 2024 study “Catastrophic and persistent loss of common murres after a marine heatwave,” authored by a team of federal and academic scientists. Their analysis compared pre- and post-heatwave breeding counts and carcass recovery rates to estimate excess mortality.

The seabird die-off dwarfed previous ecological disasters by scale. The Exxon Valdez oil spill, long considered a benchmark for wildlife loss, killed roughly 250,000 seabirds in 1989. In contrast, the murre collapse was fifteen times larger, yet has prompted no similar regulatory overhaul or restoration funding.