As the Jillaroos prepare to celebrate 30 years since their first Test, NRL.com is shining the spotlight on some of the unheralded players who played a key role in the rise of women’s rugby league. This week in our Jillaroos Journey series is Jillaroo No.64 Karley Banks.

Karley Banks will never forget the day Wayne Bennett called her over.

It’s summer 2002 and Bennett is putting his team through their paces in the sweltering Gold Coast heat as a thunderstorm swirls overhead.

Banks, an Australian touch football star taking the first steps in her transition to rugby league, is training at the other end of the field in anonymity.

599″, “>809”, “>959″]”

data-eqio-prefix=”video-post-screen”

ref=”root”

>

Up Next

/

Replay

Play Next

2024 Hall of Fame Induction – Wayne Bennett

That is, until Bennett yells out to her.

“There was lightning, it was raining, I was out running 400s with a mate and then we were just throwing the ball around,” Banks recalls. “Wayne Bennett starts walking over and we quickly pack up because we weren’t meant to be there.

“He says ‘hey, come here’. I thought he was going to get up me and I’d get yelled at because I knew his reputation. He asked me what I was doing, I said I was training for the Trans-Tasman touch competition. He said ‘I like your attitude’, when you’re finished come over and see me.”

Little did he know it at the time, but Bennett had just provided a bridge between touch football and tackle rugby league. It’s an impact that continues to be felt today, with Banks playing a hands-on role in the emergence of a host of touch players who have developed into NRLW stars.

Karley Banks is the coach of the Indigineous All Stars touch team.

Rather than yell at Banks for using a field he had already booked, Bennett praised her for training through the rain and invited her to join in with the likes of Scott Prince and Carl Webb for a game of offsides touch.

The interaction was the start of a lengthy partnership, with the super coach mentoring Banks as she went on to play halfback for the Jillaroos.

So impressed was the master coach with the playmaker’s commitment, Bennett opened the doors to Broncos HQ and invited her to train alongside Darren Lockyer and Michael De Vere.

Like many players switching from touch to tackle, Banks had the attacking skillset to thrive in rugby league but the other areas of her game needed work before her Jillaroos debut eventually came later in 2002.

That’s where Bennett comes in.

“He said ‘have you ever thought about playing rugby league’?” Banks said. “I said ‘I’ve just started but I can’t kick the ball’.

“So he gives me his number and tells me to get in contact with him the next week. When I rang he was true to his word and I was lucky enough to go in on Tuesdays and Thursdays and work with their kicking coach after he’d finished with Darren Lockyer and Michael De Vere.

“I felt so privileged that I was able to learn from these guys and it fast-tracked my kicking game.”

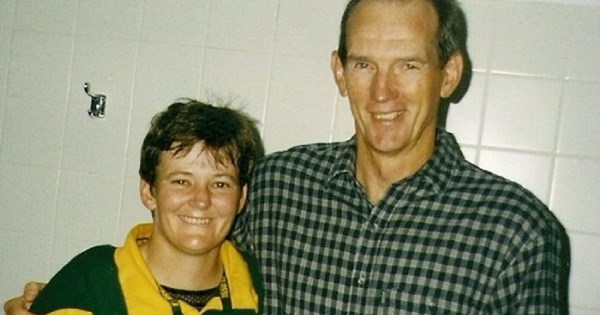

Such was there relationship, Bennett was on hand to watch Banks make her Jillaroos debut against Great Britain in 2002.

The supercoach’s generosity came at a time when female rugby league players still faced scepticism in wide pockets of the sport, many fans and administrators unwilling to give any time or resources to the women’s game.

Banks grew up in Toowoomba, next door neighbours to future Knights star Robbie O’Davis. The pair played tackle rugby league in the backyard and while the Knights legend would go on to win a Clive Churchill Medallist, Banks saw her formal sporting endeavours restricted to touch football.

That didn’t stop her, however, from joining the likes of Steve Price and Ian Dunemann for regular games of rugby league in the schoolyard at Harristown State High School.

“If we’d been able to play rugby league when we were kids, it would’ve been the best thing ever,” Banks said. “But I was restricted to the backyard and playing tackle at lunchtime with the boys.

“I got my fix of rugby league by doing that but unfortunately there wasn’t any formal competition when I was a teenager.”

With formal rugby league off the table, Banks turned her focus to touch and quickly emerged as a future star.

The playmaker was selected in Queensland junior representative teams alongside future NRL Hall of Famer Karyn Murphy and later went on to represent Australia. Eventually, however, she had a yearning for something more.

So at the age of 28, Banks began a transition to rugby league and had that fateful meeting with Bennett.

The playmaker wasn’t the first player to make the switch and certainly won’t be the last.

A quick glance at the current crop of NRLW stars highlights how important touch football has been in creating generations of rugby league players.

599″, “>809”, “>959″]”

data-eqio-prefix=”video-post-screen”

ref=”root”

>

Up Next

/

Replay

Play Next

Upton at it again

Tamika Upton, Tarryn Aiken and Hayley Maddick are among a growing group of women who played touch for Australia before switching to tackle.

The impact is clear at all levels of the game. The ubiquity of touch and tag mean players enter junior representative pathways equipped with elite-level skills.

Coaches are able to dedicate their time to the contact side of the sport, safe in the knowledge players can already catch and pass at a high level.

The flow-on effect to the NRLW is hard to overstate. Many experts have cited a direct correlation between touch and the competition’s elite standard of play.

Upton went from touch footballer to NRLW premiership winner in less than a year and said much of the league’s success can be attributed to the non-contact format.

“Some of the best players in the game have come through touch footy and you can tell by the way they run the ball and put other people in space,” Upton told NRL.com. “You’re doing that multiple times every set so it becomes natural and translates well.

“Having that background, you’re able to see what’s unfolding before you and have the skillset to make those decisions and reads on the run. There’s no tackling but it helps you know defensively what’s coming and then you can get your defensive line organised.”

While the impact of touch as a sport is hard to overstate, few figures have had as big an individual influence as Banks.

The playmaker made her Jillaroos debut at 28 and only spent a few years in the jersey, but she quickly transitioned to coaching and has spent the past two decades mentoring scores of girls and boys.

Karley Banks was named Sport NSW Community Coach of the Year for 2025.

Kurt Donoghoe, Olivia Kernick, Jesse Southwell and Ash Quinlan are just some of the current players to have passed through Banks’ programs at school or in the representative arena.

She has also worked alongside Murphy with the Titans NRLW team and hopes to one day become a rugby league coach.

Banks’ influence on the game of touch extends from the junior pathways to the elite level, with the coach revolutionising the way the game is played.

The former Jillaroo introduced the sub-box playing style and has won multiple World Cups throughout a decorated career.

Earlier this season Banks broke a 30-year glass ceiling to become the first woman to coach the NSW open men’s touch team. The Blues enjoyed instant success, defeating Queensland for the first time in eight years to win the State of Origin shield.

“It was a dream come true,” Banks said. “I had been coaching open men’s teams for 17 years before they gave me that opportunity. NSW had lost for the last eight years and to finally get the opportunity and deliver is a career highlight.

“Being able to be the first female coach, it proves that if you get runs on the board and you perform then you can get an opportunity. I hope it’s easier for the next generation of female coaches who come through.”

Having coached NSW to a State of Origin victory, Banks has one more goal left to achieve in touch football.

“Getting that Australian men’s open gig, that’s the biggest job in the sport,” Banks said. “I can’t get on the staff there at the moment. It’s disappointing, I can’t win any more tournaments than I have won.

“After 17 years in the high-performance program I want to coach at that level. I’m hopeful things will change and the next World Cup is in 2028 so anything can happen.”

It’s a goal that has proved elusive so far, with officials reluctant to put a woman in charge of the men’s side.

It’s a situation many current and former Jillaroos have experienced before, with female athletes spending much of their careers breaking down barriers.

Whether it be in the schoolyard in Toowoomba, on the field as a talented halfback or working as a coach, Banks has made a habit of taking the fight head on.

Given she’s spent more than three decades as a player and coach building to this point, she’s not going to back down lightly. And she hopes generations of future women will benefit as a result.

“The first person through the wall always gets blood on them,” Banks said. “That’s just how it is, but once you’re through then hopefully there will be a lot of people tracking through after me.

“Hopefully they’ll feel they can get there based on merit and it’s not a closed shop.”