Was studying in Dunedin in the 1990s worse than dialling into a lecture during the Auckland lockdowns?

Would you rather have cheap tertiary education and mould-induced respiratory issues (very dark academia) or eye-watering fees and a heat pump (but probably still mould)? With news that the cost of university is going up (again) let’s fire up the time machine, draft a few pints and see who had it the hardest.

Victoria University is putting its domestic tuition fees up next year. The government has raised the cap on fees increases from 2.85% to 6%. Victoria University in Wellington has immediately done so but most other universities are expected to follow their lead.

Tertiary education, and loans to pay for it, are a huge financial commitment that can have far-reaching impacts that your developing frontal lobe doesn’t comprehend. A massive 93% of the country’s $2.375billion overdue student loan debt is owed by people overseas, unsurprising given that’s when interest kicks in for most. (Inland Revenue is cracking down, and defaulting can mean trouble – even arrest, which happened last month to one woman who owed $58k.)

Generations of New Zealanders have sat around tables here and abroad nursing beers and comparing their student debt. But who actually had the roughest ride?

1960s and 1970s: Cheap if you could get in

Once upon a time, the state paid via the bursary system – established in 1962, and judged on your academic performance in the university bursary exam. The Fees Bursary covered all tuition fees for full-time study. Those in the top 3-4% of scholarship grades got more money, and there were also allowances for boarding and travel. Passing three units in a bachelors of art or science meant you got an allowance too, according to 1966’s An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, which doubled in your fourth year. “No special obligation is laid on the student,” explained Department of Education senior inspector Harry Archibald Reeves. In 1966 a science course at Otago was £80 a year, and arts £60. In 1976 a new tertiary bursary was in the works (declared a “shambles”).

Just 1967 things (Image: The Press, Christchurch City Libraries)

1980s: OK groms, time to start paying

Studying became more expensive in the late 1980s. By 1982, the entry fee to sit the bursary exams was $53 – half the $100 awarded for a B bursary (an A bursary was $200). By 1985, only one in every 15 nursing students was offered bursary (fixed at $10 a week since 1972) with 160 available. In 1989 Labour introduced a means-tested allowance and university tuition fees. Set at $129 annually, they rose to $1,250 the following year.

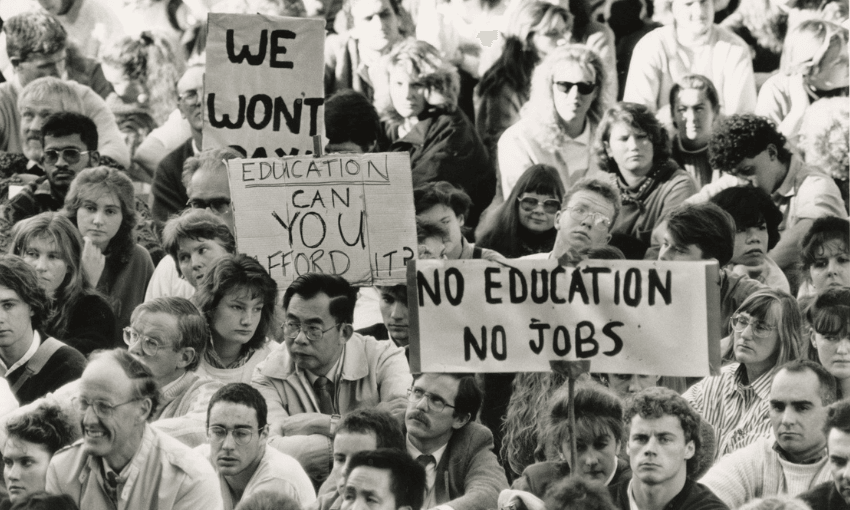

University of Canterbury students and staff protest rising tertiary fees in 1989 (Photo courtesy of Allied Press)

1990s: A wild west of unregulated fees and high-interest loans

The flat rate was scrapped by National in 1991 and the student loan scheme was introduced in 1992. From then until 2000 the country had an “unregulated fee environment”. It was a grim time to study. “When I started at university in ’93, student loans had just been introduced. Fees were around $1,500 ($3,200 today),” one unlucky soul recalls. “But you could draw on the loan to the tune of tens of thousands across your degree for anything you pleased. This provided a timely stimulus in a straitened economy, with a particular boost to fashion boutiques, hostelries and drug dealers.” Interest was market rate and comprehension of compound rates were nil, so it set much of their generation up for a future of “servitude and misery”.

Back then, everyone paid interest on student loans and it began when your loan did. Eventually, Labour made some changes; in 2000 students still studying were no longer charged interest.

At least flats were cheap, right? In 1998 Dunedin, $65 would get you a “massive” room in a “total shit hole”, but it was still easy to rack up debt. Part-time work was hard to come by, so if you needed money, you could call MSD for a living costs deposit. The minimum was $400 and the phone system was automated. “I owned a lot of Nom*D and many CDs,” one Spinoff staffer remembers. “No one spent their course-related costs on course-related costs back then.” By the time they’d left university six years later, they owed more than $75k.

In the late 1990s, undergrad fees for one Auckland student were around $2,000 a year, with post-grad more than $5,000. A loan covered it all and was $40,000 by the time they finished. They were flatting ($90 a week in Eden Terrace) but were ineligible for the allowance, so borrowed living and course related costs, in addition to working, to get by. “I was 17 and could just call the helpline and get $1,000 immediately deposited into my account.” There were other workarounds too. “Lots of people were getting married to access the student allowance – that somehow overrode the parental means testing.”

2000s-2010s: Students start taking shit seriously (kind of)

In 2006 all loans became interest-free as long as you met requirements for New Zealand residency, but debt was scary. “Desperate not to get a student loan”, one Spinoff staffer qualified for a scholarship and student allowance, making 2010s-era University of Auckland (when a full-time semester was $3,000-$4,000) economically doable. Student allowance was $215 and most rooms, in a landlords market, were $140-180 a week. “There was a lot of protest at the time that student allowance/living costs barely covered rent.” Unlike the halcyon days of calling an automated phone line, navigating Studylink was “a nightmare”.

After winning a partial scholarship, one Auckland University student turned to MSD for the rest. They had a part-time job, “but still took all the government money” they could. Qualifying for the allowance, they also borrowed living and course related costs, and a loan for fees. Rent cost under $200 a week and food was $100 max. By the time they left in 2017 (without finishing) their loan was nearly $40k.

Otago University in 1980 from the Eric Young Collection Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections

2020: The stakes are high, so is the cost of everything

A new generation is enjoying (more) affordable study thanks to the fees-free year. Introduced by Labour to make education accessible, by the end of 2019 less than a third of recipients came from low-decile schools. The majority of fees-free students were enrolled in medicine at Otago. By January 2025 National had swapped the fees-free policy to the final year (rewarding commitment) with “no double-dipping” allowed.

Getting in before that was someone enrolled at AUT in 2019. “My first year was free!” After that each paper cost around $800-$1,000. Flatting cost $200 a week for rent and utilities. They qualified for the full student allowance (“I have no bank of mum and dad”) but borrowed course-related costs. They left, without graduating, $12,000 in debt and wonder about the value-for-money of studying during a pandemic. “Students during the Covid years (especially in Auckland) shouldn’t have had to pay full tuition when we weren’t on campus for large chunks of the year. Not getting a discount in that respect kinda sucked.”

Remote learning also impacted expectations around flexibility. In 2022 over 3000 people petitioned for all lectures at Victoria University ($15.7 million in the red that year) to be recorded, partly due to students “having to sacrifice time in class to pay bills”.

Universities have been trying to get students back in lecture halls. Domestic enrolments are up 4.5% (and almost 8% at Auckland and Canterbury). Uni halls are going up, literally. Auckland University built a “US-inspired” student village where the cost – which ranges from $350 a week for a single to $625 for a family unit – includes rent, utilities and wifi. More multi-million dollar builds are planned.

Prices are rising too. A single room in a catered hall at Vic will be $578 a week next year, up from $512. At Canterbury, you could pay as much as $766. Residents at Auckland University halls initiated a rent strike in 2014 after an 8% increase, demanding reductions and arguing full-time students “shouldn’t be expected to work 10, 20, even 30 hours just to pay rent”.

As The Spinoff heard this week, in 1975 a full-time student with a pre-school child and no income found their benefit “liveable”. A similar situation in 2025 would qualify for a student allowance of up to $519.81 a week after tax, but average Auckland rent is $689 a week and on-campus childcare at the University of Auckland costs a student between $308-$177.50 full-time.

International students pay a lot more (at Auckland an undergrad ranges from $48,310 to $86,561 for 2025) and universities have been able to charge them full fees since the Education Amendment Act was passed in 1990. More than 20,000 international students are currently enrolled full time at New Zealand’s eight institutions.

While the current cohort is diligently studying (and racking up debt), recent modelling predicts AI could replace 50% of entry-level white collar jobs within five years. Shit.