About 12,000 years ago, a human living in the Arabian desert carved “incredibly beautiful” rock art into a cave’s wall. While we do not know the prehistoric artist’s intentions, archeologists studying the art and tools found alongside it indicate that fresh water sources in the area allowed humans to expand in the region. These rock engravings of camels, gazelles, and other animals dating to between 12,800 and 11,400 years ago and what they could mean are detailed in a study published today in the journal Nature Communications.

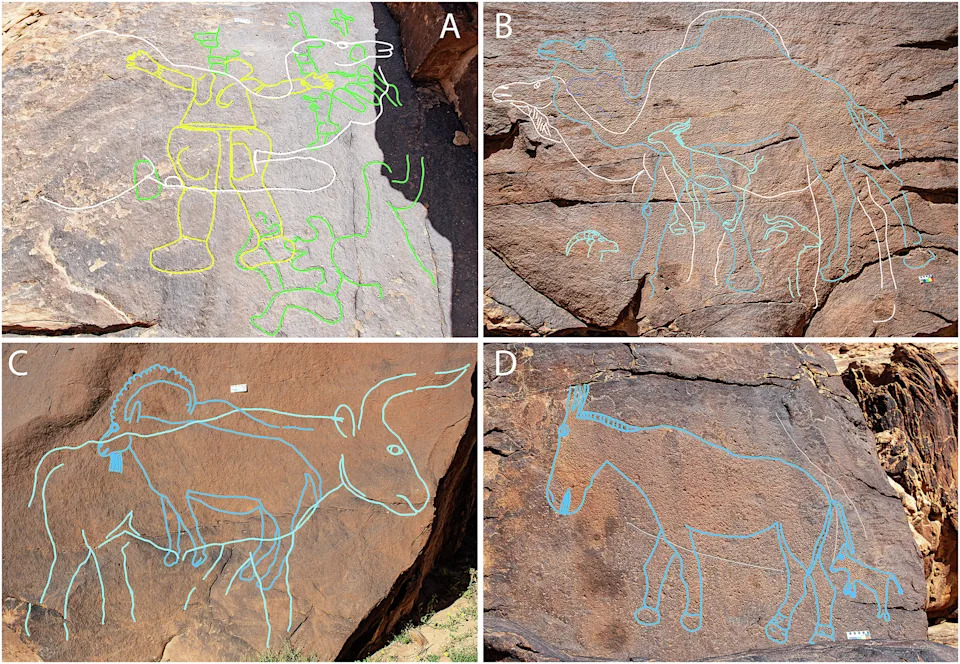

Rock art panels at Jebel Arnaan. Tracings highlight the layering of engravings, showing phase 1 in green, phase 2 in yellow, phase 3 in white and phase 4 in shades of blue. Image: Guagnin et al., Nature Communications (2025).

Follow the water

Archaeologists have limited evidence of human life in northern Arabia between 25,000 to 10,000 years ago. During this period, the area was likely arid and dry, but humans in other regions of the Middle East successfully adopted farming and herding practices across a wide range of environments.

Human activity in northern Arabia was believed to have begun around 10,000 years ago, due to water oases that began to pop up. The art-filled cave was uncovered in the Nefud Desert, in present day northern Saudi Arabia in 2023. It’s now offering clues to the life and the climate of the area around 12,000 years ago, pushing back the timeline of human activity in the Nefud by about 2,000 years.

“It was probably similar to today, perhaps a little bit wetter, but not much,” Dr. Maria Guagnin, a study co-author and archaeologist and rock art researcher from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, tells Popular Science. “We know there were shallow, seasonal lakes, but it was probably too dry for vegetation to become established.”

From the lake sediments and the location of the rock art, the people living here may have used a network of routes to travel between the shallow lakes. According to Guagnin, it’s not quite clear how they survived the dry season.

“Either they found deeper pools of water in the mountains, or perhaps they moved to other regions and then came back,” says Guagnin. “We know they must have been very mobile–they have shell beads that came from the sea, which is at least 320 km [198 miles] away.”

‘The sort of evidence rock art researchers dream of’

The giant rock art and stone tools found inside of the cave indicate that this extra water availability would have supported human life. The rock art includes over 130 life-sized engravings of recognizable animals living today and also an extinct species of a cow-like mammal called an aurochs.

“The rock art is incredibly beautiful,” says Guagnin. “It shows life-sized, naturalistic camels, ibex, gazelles, wild equids and an aurochs. It is rare to find so many panels that are so well preserved and still visible today. This means we can actually reconstruct how they were placed in the landscape.”

Some of these engravings are over six feet tall, with the largest sitting on a cliff about 127 feet off of the ground. According to Guagnin, a very shallow ledge is the only platform in front of it.

“That means the engraver must have stood directly in front of the rock surface while engraving,” she says. “They would not have been able to see the whole animal–and yet they produced a perfectly proportioned, naturalistic camel engraving.”

Drone image of monumental camel engravings carved 39 meters above the desert floor at Jebel Misma. Image: Sahout Rock Art and Archaeology Project.

Today, that panel is almost invisible because it sits very high up on the cliff, and rock art this old is difficult to see from a distance. It could only be seen for about one hour in the morning, when the sun is rising over the mountain and the light hits it at the correct angle. “We were very lucky that a labourer who was working with us, Saleh Idris, spotted it,” she says.

The team also found 532 stone tools. Guagnin says that finding an engraving tool within the sediment is “the sort of evidence rock art researchers dream of.” Their shape could indicate some cultural connections to present day cultures in the Middle East. The team believes that some of the same groups of people may have made the rock art and the stone tools, but are not quite certain and direct links between the tools’ creators and rock art are difficult to glean as of now.

An ‘El Khiam’ arrowhead uncovered at Jebel Arnaan, Saudi Arabia. This tool type is well known from early Holocene sites in the Levant, highlighting long-distance links. Image: Sahout Rock Art and Archaeology Project

One aspect of the art that is clear, and that is the importance of one particular animal commonly associated with desert life.

“The symbolism of the camel was very important to them,” Guagnin explains. “The rock art often shows male camels during the mating season, which coincides with the wet season. We think this probably shows how important the arrival of rain was for survival in the desert.”