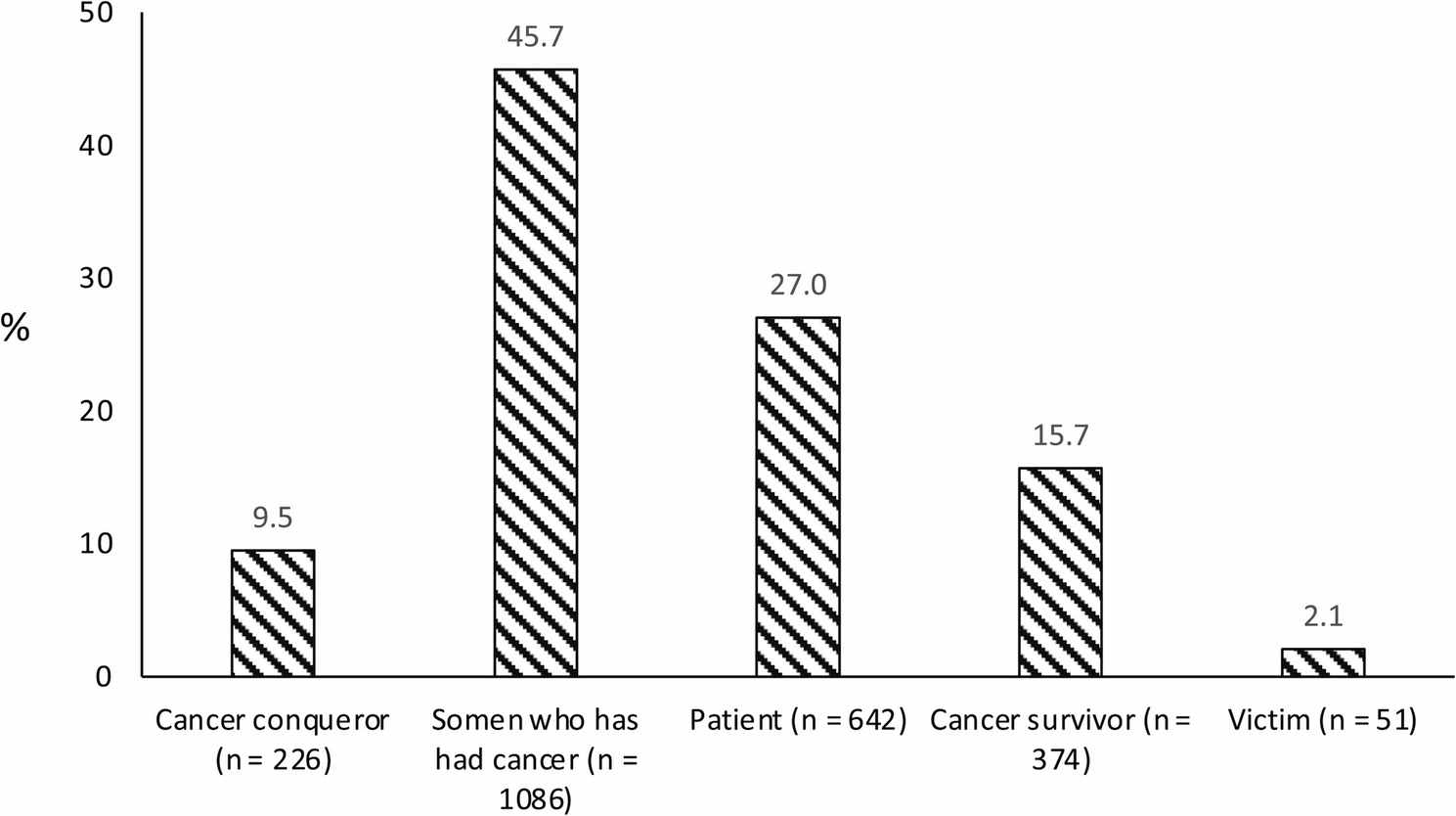

Many men affected by PCa reach an age beyond 75 after initial cancer treatment. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of PCa, the treatment, and the regular follow-up may affect the self-perception and identity in these men even years after the initial diagnosis [11, 13, 25]. Further, old age is often accompanied by a general decline in fitness, health, and social interactions. However, it is unclear how these factors may be associated with specific cancer-related identities. Our data of 2,379 older men affected by PCa with a median follow-up of 17.9 years after the diagnosis of PCa and treatment with radical prostatectomy shows a gradual increase in frailty, comorbidities, and perceived loneliness with increasing age, suggesting that these factors might also interact with the general outlook on life and the perceived significance of one’s PCa. Concerning their PCa experience, most men identified as “someone who has had cancer” (45.7%), followed by “patient” (27.0%). More emotionally connoted cancer-related identities were reported by every fourth man (“cancer survivor” 15.7%, “cancer conquerors” 9.5%, “victim” 2.1%) [5, 10, 13, 16].

Identification as a cancer survivor and victim in older men affected by prostate cancer

The prevalence of frailty, loneliness, and the number of burdening comorbidities was highest among the men identifying with more negatively connoted cancer-related identities, “cancer survivor” and “victim”. Although identification with the term “cancer survivor” was initially intended to empower individuals affected by cancer to engage more actively with their disease to improve psychological resilience, results from this analysis, as well as previous research, have shown that in men with PCa identifying as a “cancer survivor” seems to reflect a more negative, subjectively demanding cancer experience instead [5, 13, 14, 26]. Our results also show that identification as a “cancer survivor” correlates with a lower overall health status. Interestingly, this indicates that more subjective health issues do not reduce the personal significance of PCa but seem to be associated with a more negatively connoted outlook on this additional health burden.

Identification with the term “victim” was low, comparable to previous research [5, 10, 14]. Although these men represent only a minor portion of our sample, our data suggest that these men were more likely to experience severe loneliness and overall lower well-being. Interestingly, clinical factors offering an extraordinary disease course were not more common in men identifying as “victims”. This indicates that a negatively valued cancer identity among older men affected by PCa may depend mainly on subjective, not primarily, PCa-related factors and the lack of a functioning support system [8, 18, 19].

Neutral cancer-related identities in older men affected by prostate cancer

Previously, research has shown that most men affected by PCa and treated with radical prostatectomy identify with a neutral, descriptive cancer-related identity such as “someone who has had cancer” or “patient”. These identities are primarily associated with the objective disease course and reflect the current disease status. Our results support these findings and show that these identities seem to be independent of PCa-unrelated or aging-related factors. Regarding the identification with the term “someone who has had cancer”, our results are in line with previous research, which showed that this was more common among individuals with an uneventful follow-up, which were more often cured by primary therapy and had fewer side effects [5, 10, 14]. Additionally, our data revealed that signs of anxiety were less common among these men. Overall, this suggests that many older men who have been successfully treated for PCa and subjectively do not regard this disease as a current health problem tend to perceive themselves in a very neutral way regarding their cancer experience and consider PCa as something of the past. These men also seem less likely to display signs of cancer-related distress negatively affecting well-being and probably do not require specific psycho-oncological support.

Every fourth man in our sample identified as a “patient”. Previous research has proposed that identification as a “patient” might be a sign of passiveness when dealing with cancer, which might lead to a lack of coping [14, 15]. However, it has been repeatedly shown that among men affected by PCa, the identification as patient is a neutral portrayal of an ongoing treatment without signs of a negative impact on mental health [5, 10, 26]. Our data also reflects these assumptions, showing an association between ongoing therapy and recognizing PCa as a persisting healthcare problem with the identification as a “patient”. In contrast, no association emerged with decreased overall well-being or psychological or physical fitness. Moreover, identifying as “patient” was associated with fewer burdening comorbidities and a higher likelihood of being in an intimate partnership. These results underline the assumption that in older men, identification as a PCa “patient” might not be a sign of being passively overwhelmed by cancer but rather a sign of still having the physical strength and social support to receive ongoing cancer therapy. Additionally, compared to younger individuals affected by cancer, older men with an intact social support system might be used to illnesses among their peers [3, 23]. Therefore, they might consider being a “patient” not a sign of weakness but a natural part of life. Accepting PCa as a chronic condition and identifying as a PCa “patient” might help these men to incorporate this experience into their current life situation in a neutral way without leading to additional distress.

Active cancer identification in older men affected by prostate cancer

Every 10th man in our sample identified as a “cancer conqueror”, representing an active and positive disease engagement, embracing fighting and overcoming the struggles of a cancer diagnosis. The term “cancer conqueror” emphasizes actively overcoming PCa. Previous research has shown that an active identification with overcoming cancer seems to be associated with positive coping and improved psychological outcomes [14, 27]. In our sample, identifying as a “cancer conqueror” was more likely among men with higher overall reported well-being. These results follow previous studies suggesting that a self-confident, positive outlook toward one’s cancer experience might be associated with a better psychological adaptation [10, 11, 15, 27, 28]. Interestingly, the regression analysis did not detect any associations between the identification as a “cancer conqueror” and signs of overall higher fitness or fewer age-related health problems. This suggests that it seems advantageous to encourage men, regardless of age and age-related comorbidities, who are open to actively integrating their cancer experience into their personality in an empowering way to pursue this approach further.

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this analysis must be considered within certain limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design, assumptions on causality and developing a particular cancer-related identity must be treated carefully and further investigated in longitudinal studies. Based on the associations that emerged, it remains unclear whether perceived health status triggers identification with a specific cancer-related identity or whether actively identifying with a cancer-related identity leads to a particular psychological adaptation. Moreover, an unknown moderator, such as personality traits and the general outlook on life, could affect the identification with a specific cancer-related identity and subjective health status. By only including older men affected by PCa, our results do not represent other types of cancer and different life circumstances. Especially in younger individuals affected by cancer, self-perception might differ, and other disease-related factors might be of more objective and subjective importance. However, PCa is one of the most diagnosed types of cancer, and the number of older men treated for PCa with radical prostatectomy will further increase in the coming years. This makes research on these men highly relevant to understanding more of their demands from the healthcare community. Lastly, it should be noted that this study was conducted in Germany. The translation of terms such as “survivor” or “conqueror,” which are associated with distinct cultural interpretations, may result in alterations to the nuances of meaning, and therefore the results of this study may not be applicable in other cultural contexts. Further research is necessary to address how diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds might influence the understanding and usage of these terms among individuals affected by cancer. Lastly, it must be pointed out that 31% of contacted men did not return the questioner. Therefore, we cannot conclude whether these men differ in regard to their psychosocial status compared to the men that returned the questionnaire. This limits the generalizability of our date. Nevertheless, the median age and clinical characteristics, such as cancer stage and prostate cancer therapy, did not differ significantly between those who responded and those who did not.