On a Gisborne vege farm, a soil health experiment produces salad greens, sweetcorn and hopeful signs for a sustainable farming future.

Gordon McPhail swivels his laptop to reveal the view from his office window: green stripes stretch beneath the winter sun. “That’s a cover crop!” he says to me over Zoom.

Although he’s on a vege farm where your spinach, mesclun and broccoli comes from, these leafy greens won’t end up in lunchboxes or on dinner tables. Instead, the neat rows of barley and black oats have been planted to protect the “lifeblood” of the farm: the soil.

“With some input from us and mother nature, the soil is the sponge, the nursery. And if it’s not in good shape, you’ve got no resilience,” says McPhail, general manager of farming at LeaderBrand. “In our tired paddocks, we can definitely see the outcome in lower yield.”

After seasons and years of intense cultivation, the soil is knackered – not just here, but on vege farms across Aotearoa, says Matt Norris, scientist at the Bioeconomy Science Institute, Plant & Food Research group.

By constantly churning it up, leaving it bare and exposed to wind and water, conventional farming methods have drained the soil of organic matter. This is the food that fuels a diverse ecosystem of soil microbes. It’s the sponge that holds onto water, and the glue that creates the soil’s structure, binding essential nutrients that plants need to grow.

“We’ve had to change our whole approach to how we look at soil,” McPhail says. At the Gisborne farm, they’ve switched up their physical operations, establishing permanent beds and implementing traffic lanes for heavy machinery to reduce soil compaction. They’ve also tinkered with some tools from the world of regenerative agriculture.

Now, two years’ worth of testing is yielding juicy scientific data – and glimpses of a different future for vege farming.

Two years spent assessing soil health has yielded some hopeful results (Image: Supplied)

Regenerative agriculture, or regen ag for short, is a holistic, sustainable approach that aims to generate positive outcomes for nature and people. Unlike organic farming, which comes with strict rules, regen ag is flexible and less defined. McPhail sees it as a toolbox – a suite of sustainable interventions that farmers can draw on to suit their land, goals and context. “We want to improve soil structure and organic matter in our soil,” he says.

So, from this bag of ripe regen tricks, LeaderBrand picked two: cover crops and compost. You’re probably familiar with compost – a superfood for soil rich in organic matter and nutrients. Cover crops are grown in between the “cash” crops – the plants harvested for sale and eating. The cover crop’s roots stabilise the soil, mopping up excess nutrients, before they’re chopped up and incorporated back into the earth, providing food for hungry soil bugs.

Implementing both compost and cover crops on a commercial vege farm isn’t as easy as you might imagine. Compost carries food safety risks that have to be managed, and there are rules about how much you can apply in one go. Plus, it’s heavy to truck around. Cover crops require careful planning to make sure there’s still enough time to grow the stuff you’re actually going to sell (and eat). It’s also more on-the-ground work added to the farmer’s already very full plate.

Cover crops keep the soil covered and nourished after a cash crop is harvested (Image: Supplied)

A partnership with Woolworths and scientists at the Bioeconomy Science Institute provided the horsepower to launch headfirst into testing cover crops and compost in a scientifically rigorous way.

“Being able to quantitatively assess an effect is really useful, rather than just eyeballing it,” says Norris. He wasn’t expecting any big changes over the project’s timeframe, “Simply because, often these effects take five, six, seven years or more to really come to the fore,” he says.

That longer term outlook was a drawcard for Woolworths, offering a way to explore their sustainability ambitions around stewardship of natural resources.

“We know that New Zealanders want to see us working alongside our suppliers to support the adoption of sustainable food production practices,” says Catherine Langabeer, head of sustainability at Woolworths.”It’s right up there alongside support for local production: an interest in provenance, knowing where your food comes from and how it’s grown.”

Lettuces popping up (Image: Supplied)

Here, the aim was to grow food in a way that regenerates worn-out soil. In the trial, two sites were set aside for testing out compost and cover crops. At Site 1, used for growing winter salad greens, the soil was sandy, lacking organic matter and prone to wind erosion. At Site 2, a sweet spot for summer sweetcorn, the heavy clay soil formed dense clods and was depleted of carbon.

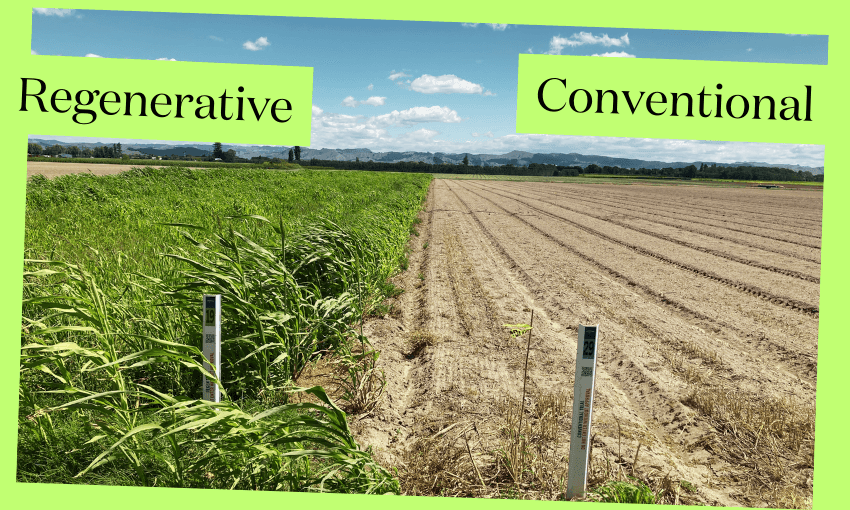

Each site was split into two: a regenerative zone and a business-as-usual zone. The regen zone received compost applications and incorporated cover crops into the growing rotation. Both zones got a dose of fertiliser (lab experiments and pot trials revealed that the compost alone wouldn’t deliver a sufficient nitrogen hit to meet the crop’s immediate needs).

As the seasons wheeled by, Bioeconomy Science Institute scientists monitored a range of soil health indicators. After one year, signs of microbial life intensified in the regen zones. The soil’s resident bacteria and fungi appeared to be feasting – likely on the residual cover crops, Norris says, which serve up a sugary snack.

After two years, the sandy soil characteristics in the winter green field hadn’t changed much. But at Site 2 – the heavy clay sweetcorn paddock – the soil has begun to transform. The thick wedges of clay are fewer, with more crumbly texture indicating better soil health.

“That was really encouraging and somewhat surprising, given the short duration. Even in just two years, you can start to shift the dial,” says Norris.

“We’re seeing soil structure that is easier to work at lower cost,” says McPhail, who is buzzed about the results. Harvests were maintained or improved in the regen zones. Using one particular cover crop, a legume called vetch, even boosted the soil’s nitrogen enough that they could reduce fertiliser inputs by 34%. And the produce grown in these science experiments did end up in the fridges and pantries of customers too.

One of the winter greens research sites (Image: Supplied)

But it wasn’t all blooms and sunshine – this is a farm exposed to the elements, battered by Cyclone Gabrielle in early 2023. Then, in winter 2024, stubby-root nematodes hit hard. These microscopic roundworms living in the soil began to stab holes in roots at Site 1, sucking out the plant’s insides like a smoothie through a straw. Above ground, the baby spinach began to yellow and wither.

Nematode infection had been an ongoing problem in this paddock, but this was a particularly bad flare, and the crop losses were heavy. Still, the regenerative side was greener than its conventional counterpart, yielding more marketable spinach. Norris reckons the compost may have boosted the regen crop’s resilience.

But compost proved tricky to work with. A bad batch on the first summer’s sweetcorn dented yields. McPhail is now keen to pivot to exploring another soil health supercharger: biochar. Similar to charcoal, this carbon-rich residue can hold onto water and nutrients in the soil and enhance the action of soil bugs. “We want to put some biochar in some of those trials and see if we can get more of a consistent sort of reaction,” he says.

Experimenting in this big, bold way has captured attention. McPhail says the whole LeaderBrand team can appreciate the regen approach, watching it play out on-farm, side-by-side with controls, with their own eyes. Other growers, too, are catching on, with heaps of interest at on-site field days, Langabeer notes. “How we practically empower our growers to adopt these practices that we’ve trialled is next,” she says.

McPhail believes “wholeheartedly” in the regenerative approach, and sees it as integral to vege farming’s future. “I don’t see a way forward without it, in terms of being sustainable. It’s just how we can fit that into our system, and how we actually value it,” he says.

Because ultimately, it all comes back to that soil, the lifeblood feeding New Zealanders. “Without healthy soil, or any soil, you’re not gonna get very far,” says Norris. “Not just maintaining our soil basis, but actually regenerating it so that we have something to work with in the next 50, 60, 100 years – that’s our foundation.”