This is a guest post by Darren Davis. It originally appeared on his excellent blog, Adventures in Transitland, which we encourage you to check out. It is shared by kind permission.

A Detailed Business Case for the electrification of the Golden Triangle’s rail network has been underway for a while but information recently shared by KiwiRail with Waikato’s Regional Land Transport Committee sheds some light on their emerging thinking on what this might look like.

But first some context on the Golden Triangle (feel free to skip this if you’re already familiar with the Upper North Island):

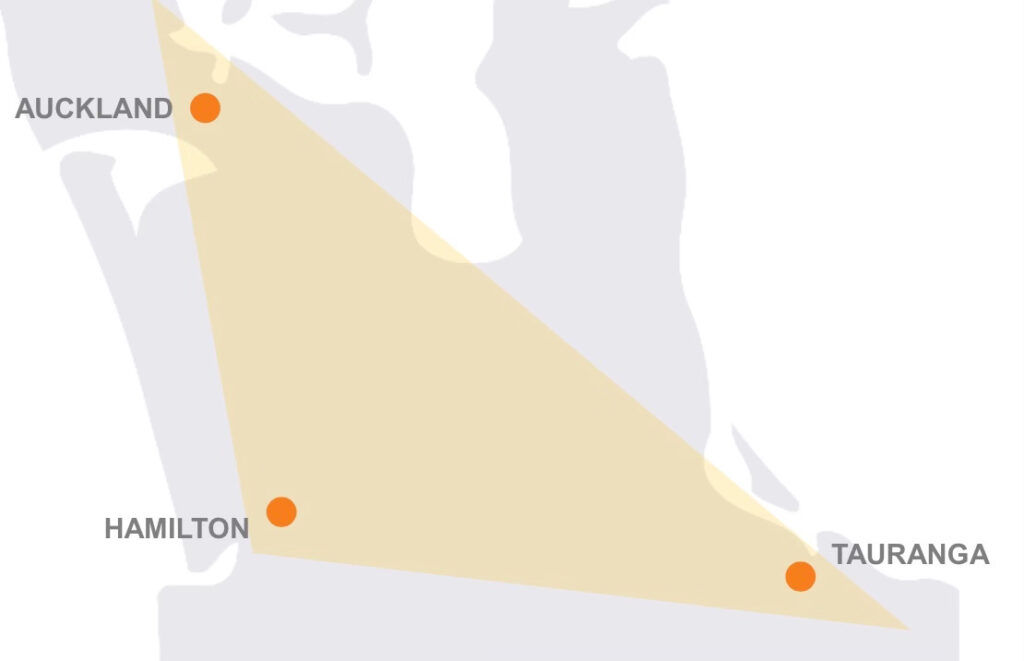

Tāmaki Makaurau/ AucklandKirikiriroa/ HamiltonTauranga Moana Aotearoa’s Golden Triangle. Image credit: KiwiRail

Aotearoa’s Golden Triangle. Image credit: KiwiRail

Some fun facts:

The three cities of the Golden Triangle have a combined population of 2.141 million or 40 per cent of New Zealand’s populationIt is projected to grow by 35 per cent in the next 25 yearsIt has 56 per cent of the nation’s freight movementsIt has more than half of the nation’s building consents KiwiRail EF class electric locomotive. Image credit: DoctorFosterGloster CC BY 4.0

KiwiRail EF class electric locomotive. Image credit: DoctorFosterGloster CC BY 4.0

And one un-fun fact:

One leg of the Golden Triangle, Tauranga, has no passenger rail

From Auckland, the Southern Motorway extends 45 kilometres to the south and becomes the Waikato Expressway at the top of the Bombay Hills, the regional boundary between Auckland and the Waikato. From there, the Waikato Expressway stretches 101.4 kilometres as four lane dual carriageway to past Cambridge. On 22 September 2025, Waka Kotahi/ NZ Transport Agency was granted consent for a further 16 kilometre extension of the Waikato Expressway from its current terminus to the recently completed roundabout at the intersection of State Highway 1 and 29.

From this point, State Highway 29 heads east towards Tauranga as two-lane state highway with periodic passing lanes, including the steep ascent, peaking at around 450 metres above sea level, over the Kaimai Ranges towards Tauranga. At the Tauranga end, enabling works for an extensive upgrade of State Highway 29, including further four-laning, are underway in Tauriko.

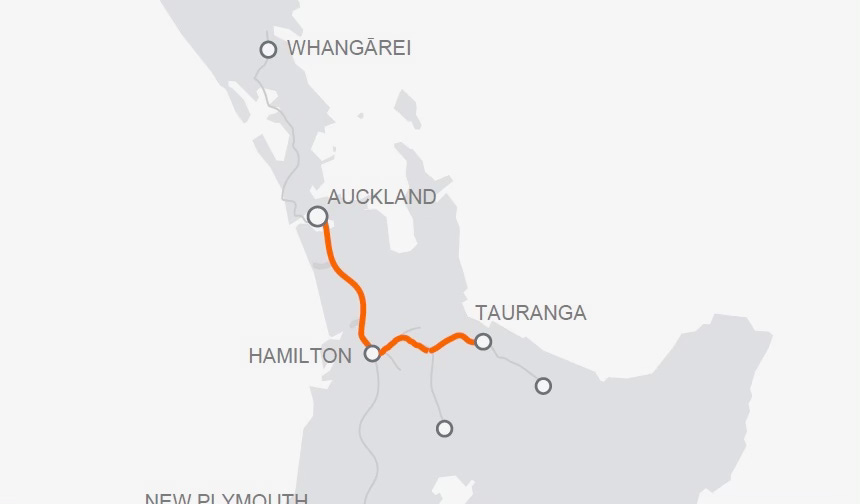

The North Island Main Trunk line extends 138 kilometres from Waitematā (formerly Britomart) Station in Auckland to Frankton Junction in Hamilton. It is double-tracked for this whole length, except through the Whangamarino Swamp and across the Ngāruawāhia Bridge, and tripled-tracked between Westfield and Wiri Junctions in Auckland. The first 52.3 kilometres from Waitematā Station to Pukekohe are electrified at 25kV AC as well as the two kilometre or so section from Te Rapa to Frankton Junction.

Golden Triangle rail. Image source: KiwiRail

Golden Triangle rail. Image source: KiwiRail

From Frankton Junction, the unelectrified East Coast Main Trunk extends eastward to Tauranga, Mount Maunganui and beyond to Kawerau as single-track line with 11 passing loops between Hamilton and Tauranga. But unlike State Highway 29 which has to climb over the Kaimai Ranges, the East Coast Main Trunk goes under the Kaimais in Aotearoa’s longest rail tunnel at 8,896 metres long. This gives rail a significant advantage over road.

While rail dominates freight flows between Mount Maunganui/ Tauranga and Hamilton, the last time passenger trains ran east of Hamilton was the final run of the Kaimai Express on 7 October 2001.

Kaimai Express at Hamilton Frankton Station. Image credit: Weston Langford Railway Photography, CC BY-ND 4.0

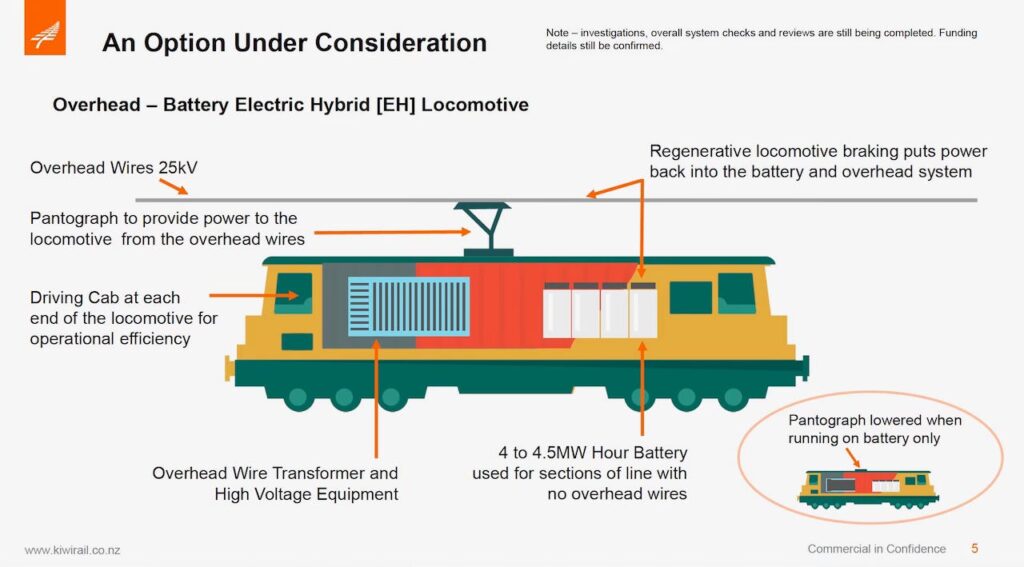

Install 25kV overhead wires and undertake other necessary infrastructure works to electrify the North Island Main Trunk between Pukekohe and Te Rapa in HamiltonIn addition, some overhead wires may be required east of Hamilton to ensure that the electric hybrid locomotives have the necessary range and reliability to reach Tauranga and Mount MaunganuiInstall locomotive battery charges in key railway terminusesUndertake the procurement of the new EH locomotivesThese activities are expected to take 4 to 5 years from design to commissioning

KiwiRail electrification option. Image source: KiwiRail presentation to Waikato Regional Land Transport Committee, 8th September 2025

This would enable is freight trains between Auckland and Tauranga use the overhead power between Auckland to Hamilton then run mostly on battery power between Hamilton and Tauranga with no requirement to change locomotive for the journey. While the train is unloaded and loaded in Tauranga the Electric Hybrid locomotive battery can be re-charged for the return journey to Hamilton.

This would mean that the entire North Island Main Trunk between Auckland and Palmerston North would be electrified at 25kV AC. And of course, Electric Multiple Auckland electric multiple units would be able to operate south of Pukekohe and hybrid electric passenger trains, similar to the bi-mode rolling stock being acquired for the Lower North Island would be able to run on the North Island Main Trunk to Palmerston North as well as in hybrid mode to Tauranga.

KiwiRail advises that the next steps are:

Complete the Detailed Business Case by the end of 2025 to identify the best and preferred electric solution plus the staged delivery pathwayAfter this it is expected that further work on the funding options will be discussed with key stakeholders. This will include exploring funding options for the delivery stages from within KiwiRail and potential Government budget bids.It is also likely that further technical work will be recommended on the preferred option to further increase confidence in the programme estimates and help narrow the risk contingency range.

This information is interesting and potentially great news for the Golden Triangle of the Upper North Island. But if you read the fine print of the Rail Network Investment Programme, then the story for the rest of Aotearoa is rather more sobering:

These investment priorities over the next 3-year period are:

improved efficiency and productivity of works deliverymaintaining asset condition/service level ratings in Golden Triangle priority routessafety and compliance with minor decline in service levels (remaining priority network routes)safety and compliance with moderate decline in service levels (secondary routes)safety and compliance with significant decline in service levels (tertiary routes)

What this means is that only the Golden Triangle and Auckland and Wellington metro networks are being maintained at current levels. While the Golden Triangle are undoubtedly KiwiRail’s busiest rail freight routes, KiwiRail is a national network operator and the rail network is a national asset. The analogy of a state highway network only invested in the Upper North Island would be unthinkable and it should be equally unthinkable that only the subsection of the Upper North Island rail network in the Golden Triangle should be maintained at current levels.

The Whangamarino Swamp and the Ngāruawāhia Rail Bridge are the only single-tracked sections of the North Island Main Trunk between Auckland and Hamilton.

According to Greater Auckland’s coverage of the issue:

[KiwiRail] said that more capacity could be created by slightly lengthening the passing loop in the middle and upgrading the signalling to allow for high-speed arrivals and departures and to simultaneously berth – which is the ability to have trains enter the swamp at about the same time from each end. This is something not possible with the existing signalling system, which dates from the 1960s. Elsewhere, more capacity could come from improvements like new or lengthened passing loops.

While we may be able to eke out some additional capacity by doing this, it would be hard to imagine the Waikato Expressway having a 12 kilometre long single lane bridge with a passing bay in the middle. This goes to show the huge disparity in thinking, and level of ambition, between roading and rail projects.

That said, the Whangamarino Wetlands are a highly sensitive environment with high ecological and Mana Whenua values. It is the second largest wetland complex of the North Island, encompassing a total area of more than 7200 hectares It is listed as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention.

It is located within the rohe of the Waikato-Tainui iwi (tribe) and is considered a taonga by local hapū. Early Māori utilised the wetland as a source of eel/tuna and birds for food, and flax/harakeke for traditional cultural purposes. The rivers of the wetland were used for travel and recreation and the peat margins were used to preserve taonga such as waka, tools and weapons. Dense vegetation inhibited further use of the wetland, although it was used as a sanctuary during the New Zealand Wars.

Given this, it is likely that a albeit not particularly cheap solution could be delivered that is better for the wetland than the current single-track corridor through the swamp, built in the days when environmental and Mana Whenua considerations were not exactly front of mind.

Really just one final thought. While it’s great that serious consideration is being given to further rail electrification in the Upper North Island, it’s disturbing and a case of one step forward and ten steps back that this is taking place in the context of an effective return to the managed decline of the rest of Aotearoa’s rail network, harking back to the very bad old days of the asset stripping privatisation era.

This post, like all our work, is brought to you by the Greater Auckland crew and made possible by generous donations from our readers and fans. If you’d like to support our work, you can join our circle of supporters here, or support us on Substack!

Share this