My father began to say to me a long time ago, and continues to say now, a comforting aphorism, something I’m sure he read as a quote some place, or in a biography: “They will say of you: ‘Her life was not the least of her art.’”

I can’t remember when he first said this or what action of mine would have compelled it, but it’s offered to affirm the way I have lived over the last decade or so when I am despairing of it, a life which has been so similar to his in some ways and completely divergent in others. He too is a writer and we both had other jobs we didn’t care much about until our late twenties, when we had the chance to become more fully dedicated to what we make and do.

Temperamentally, though, we are different. He remained in our hometown in Ireland and values highly the rewards of routine and unyielding structure. I have spent much of my adult life employing a magpie-ish approach to decisions about where and how I spend my days. I have lived in a number of countries and spent months at a time in others, a way of existing which was initially compelled by lack of money, but which I soon found I enjoyed for its own sake. I would leave London when I couldn’t afford rent and go someplace I had heard they may have need of a cat- or house-sitter. Once I had become a journalist, I would go on any press trip I got wind of, which is how I passed through central Portugal, Norway and Chornobyl in a single year.

If I admire my father’s rigour, how it suggests to me the appropriate respect and care one should direct toward creative work, he admires a certain elan in my own way of being, a taste for the novel and an openness to experience which befits the artist. So, which of us is right? Is there a specific way to live as an artist, one that can be taught? And if there is a correct way, one which it is possible to advocate confidently over all the infinite others, would we be willing to listen?

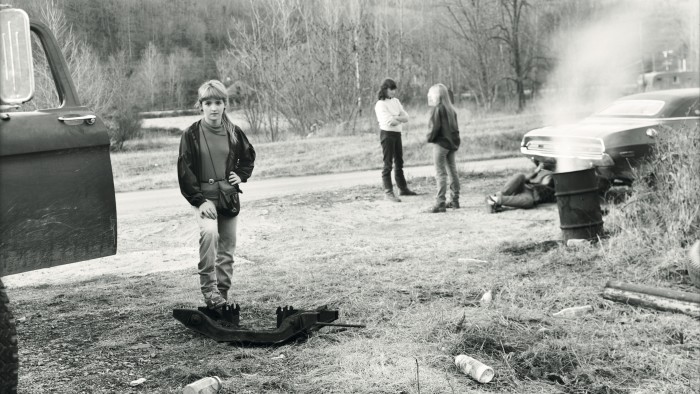

Sally Mann, the celebrated and sometimes controversial photographer who came to international renown in the 1990s for her haunting photographs of her family, herself and the Appalachian landscape she lives in, has written a book that goes some way to evaluating the question of how an artist should live. Art Work: On the Creative Life is, like her first memoir Hold Still, a confluence of writing, photographs and fragments of correspondence. It asks what one needs to lead a creative life, what mistakes we will make trying to conduct such a life, and whether we should even try to avoid those pitfalls or rather consciously accept them as part of the whole dirty process.

Sally Mann

Sally Mann

I remember the relief with which I, as an earnest teenager longing for something concrete to validate my yearning for artistry, fell upon a copy of Rilke’s 1929 book Letters To A Young Poet, having gleaned that I would find there sturdy gems of guidance. Though the tone of the letters — which is remarkably, some might say preeningly, assured for a relatively unknown writer in his twenties — inspired confidence, the contents were less prescriptive than I might have wished. “Nobody can advise you and help you,” Rilke wrote. “Nobody. There is only one way — Go into yourself.”

Becoming an artist is different from, say, learning how to run a small business. In many endeavours there are consistent principles, or “best practices”, which are required to lead to the desired outcome. But for the artist this is not true. A successful approach taken by one may be fruitless and demoralising for another. The impossibility of standardised advice is not an incidental misfortune but an inherent condition of the artist’s life. (I am not speaking here about counsel provided by teachers or trusted peers who know you and your work.) Becoming an artist is taking the idea of faking it until you make it and employing it not in the cynical fashion we ordinarily understand such pantomime, but in an act which is itself creative. That is not possible for someone doggedly following external guidelines that could be given or accepted by anybody.

Mann does not attempt to provide such guidelines. A largely glowing review of her previous book noted that a telling omission was the story of how Mann became a success. “Perhaps one subject that remains taboo is female ambition,” the reviewer wrote. Art Work is the riposte to that supposition, a rich text that functions not so much as a how-to manual as a leisurely consideration of what constitutes a creative life, furnished with lushly detailed anecdotes from Mann’s own journey, which has been one marked both by improbable luck and tragedy.

At the very beginning of her career, Mann boarded an aeroplane, sat next to a stranger and struck up a conversation with the winning insouciance of the beautiful and talented young woman she was. Upon arrival in New York, it soon transpired that her new friend Ron was a Winston — as in son of Harry, and an heir to the jewel fortune. In the moment, it was lucky enough: he tossed her the keys to his 73rd Street mansion, where she was free to crash as and when. Later, his foundation enabled a grant which redeemed her at a time of financial despair.

Luck has shaped Mann’s life, and work, in another way too. She married her husband of 55 years, Larry Mann, out of high school, proving wrong the understandable doubt of her art teacher about the durability of such a union. Finding true, enduring love early on provided another sort of blessing for the artist, the freedom not to be out there searching for it. Not to say that being in a couple is less complex than solitude, but I speak from experience when I say that there are long years, then decades, for the single person who wants a partner, where that unmet desire simply occupies too much of the mind. One of the primary things I felt upon finally meeting my partner was not just the euphoria that had accompanied previous love affairs, but the relief of having so much of myself granted back to me. A part of that self having been out wandering, away from my work.

© Sally Mann

© Sally Mann

Mann dedicates Art Work, “For Emmett/O lost, and by the wind grieved”, and refers to 2016 as her annus horribilis. That year Emmett, her only son, died by suicide, having suffered from schizophrenia and after a number of traumatic brain injuries in his earlier life. An almost unbearably moving inclusion in the book’s visual clippings is a screenshot of a part of her extensively catalogued correspondence file, which shows the folders: “Emmett / Emmett crisis/ Emmett Crisis 2/ Emmett Crisis 3/ Emmett Crisis 4/ Emmett crisis 5/ Emmett death”.

Emmett was one of Mann’s three children. Her portraits of them drew her stratospheric fame, and accompanying distress, after scandalised critics and religious conservatives objected to her portrayal of their occasionally naked forms as pornographic. When I speak with Mann over video call from her home in Virginia, I ask her about her move away from portraiture toward landscapes, and how conscious that shift was.

“Pretty much a conscious decision,” she replies, with the same eager engagement as she conducts the rest of our conversation (at several junctures, she pauses to note a book or artist I make reference to). “I don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings any more, I really don’t. I want to have a serene, good relationship with humanity. And sometimes, you can take a bad picture of someone and it can be a great picture. I don’t necessarily want to be the person who makes great art and breaks somebody’s heart.”

The received wisdom about first-person writing and art-making, specifically when a woman does it, is that it’s a kind of youthful indiscretion it may be necessary to expel before you move on to real work. But when I re-read the early texts I wrote before I knew anyone would be reading them, candid accounts of experiences and feelings which caused me shame, I admired them. Probably I’ll spend the rest of my life working to get back some version of the energy and vigour I effortlessly wept into my WordPress blog aged 20, artless as it was. Mann chose to use her children as subjects partly as a means to combine the competing demands of family life with her ambition as an artist. But she has also said in subsequent years that the capacities of the internet for fostering parasocial relationships and obsessions mean she would not choose to do so again.

I ask her whether the book is a result of a duty of care she feels toward the generations of artists coming after her, or perhaps even to the art forms themselves.

“Duty of care!” she exclaims happily. “That’s a good book title, you should take that.”

The impulse, she says, is less a custodial one than a result of taking genuine pleasure in younger people and the desire to involve her life in art with theirs. She had feared that the impact of, say, the internet and social media might have made her wisdom redundant, but she doesn’t think it has. “I’m still dealing with overarching principles which have existed for all time,” she says. Here I have a doubt, or maybe it’s only a question, one which niggles at me after Mann and I have finished our conversation. I don’t think the nuts and bolts of the internet have changed anything fundamental to art-making. I do worry, though, that the internet has compromised the one condition I consider more or less non-negotiable for the artist, which is a desire to connect with something beyond ourselves — the loneliness of the perpetual Sunday afternoon that causes us to put whatever it is down on paper in a desperate plea for any kind of response.

© Sally Mann

© Sally Mann

The internet does a dangerous thing, which is to create the illusion of connection where it doesn’t substantially exist. How could the constant availability of a seemingly infinite number of people not create a glamour like this, the lie that it can sate that oldest, direst need? I feel it now, all the time, the biggest hindrance to my own artistic life, and I am grateful that my frantic forming brain did not have the option of feeling itself falsely soothed in this way. It isn’t that I believe the internet will result in worse art than before, so much as I worry there will be more lonely and frustrated young people who won’t resort to art-making. I write to Mann to ask what she makes of this potential siloing of expression.

She replies that she believes “practitioners of almost any art need to be prepared for not getting a response, not necessarily having an audience . . . [Art] can be made without an audience and perhaps in some cases might fare better, might be more purely rendered . . . Not that I, myself, don’t wish for somebody to see what I create or read what I write — it’s just that it’s not necessary. I’m going to do it anyway. I have to do it anyway, more to the point.”

So, what constitutes an artistic life? Mann’s instinct to draw conclusions arrived with her later age — she is now 74 — which has allowed her new critical clarity about her photography and trajectory. Like the book’s title says, the story is one of work. She refers to herself as peasant stock, hardy, capable of arduous, unglamorous toiling. Even when the spirit does not move, she is capable of such steady labour.

Hard work, talent and luck. In the assessment of any creative life, all three will play a part. The precise measure of each will perhaps depend on when the artist lived, and the values of that time. Luck, when it comes to the artist, is a curious concept. It muddies with that other nebulous idea, talent, which has for a long time been out of fashion. At some point in the last century, the model of the untouchable, irreproachable genius artist fell, understandably, from favour. In part this may have to do with the multitude of sins which were and are plastered over by creative brilliance, your Picassos and Gauguins and Hemingways and Polanskis (even beginning to type the list engenders, doesn’t it, a certain weariness?).

Combine this with a more professionalised, commercially conscious approach to, say, novel-writing or painting than has historically existed, and an inevitable levelling occurred in how we wish to think about artists. There came a rebuttal to the notion of chaotic generational talents who might not bother to do anything for years and then fart out a masterpiece. In its place came an affirmation of the supremacy of hard work. When I was a young person on the internet, thirsty to write and unsure of where to begin, I searched for advice.

© Sally Mann

© Sally Mann

I saw endless blogs and inspirational slogans proclaiming that writing was all about constant work. You had to write every single day to eventually get published. Talent — that unfairly meted-out substance, that unreliable charm — counted for virtually nothing, they said, compared with consistency and dedication.

Pleasingly meritocratic as this contention is, it hasn’t seemed particularly true to me. Though I don’t know many artists or writers who don’t sacrifice and suffer over their work to some degree, I do know plenty who have worked diligently and durationally without what appears to me the equivalent notice and respect. Sometimes this has to do with the luck Mann refers to in her book, the happenstance everyone alive is subject to, or the contemporary whims of the market. And sometimes, we must admit, another artist will work half as much as we do, with far less obfuscation and self-doubt, and will achieve far more than we will, because they are better than we are; because the result of a tenth of their effort is as good as the entirety of our own.

It’s possible that some artists need to reject this idea to avoid becoming hopelessly demoralised by the unfairness of it all, but I’ve found rather the opposite in my own life. There are writers — loads of them, at least five I count as good friends — who are simply more talented than I am. These gifted bastards I conduct no mental competition with, because I don’t consider myself to be within sniffing distance of them. Luckily for me, art-making and writing are not ultimately judged by precision metrics or objective principles, so the fact I am not as good as them doesn’t make me want to stop writing. My relative inadequacy causes me no less pain than being less beautiful than Grace Kelly does. If anything, the release from rigid judgements about how to be excellent or optimally productive has given me the freedom to noodle around in the capacious mundanity of my own particular perspective, a space I will always have authority over.

Artists are sometimes asked in interviews what their daily routine looks like, or to describe the desks or rooms their work emerges from, perhaps because we believe that routine, like hard work or consistency, might hold a key to finding success as an artist. Something that struck me about Mann’s approach, another thing she and my father have in common, is their reliance on unchanging habits to smooth the edges of the everyday. Mann advises on eating the same meals and wearing the same basic outfit, eliminating choices which may otherwise bog down the schedule and take away from your time working. My father walks the same 5km route at the same time each morning, and it became a long-standing joke between us that he has never quite recovered from our usual café removing his usual sandwich from the menu 10 years ago.

Luck (in seven parts) © Sally Mann

Luck (in seven parts) © Sally Mann

To streamline like this makes perfect sense, in a way, and yet the idea of removing the daily pleasures of those choices is as unappealing to me as removing reading or writing. “It is about how you live your life, because the life you lead is your art and the art you make is your life,” writes Mann. But what dress to wear in the morning and what pasta to cook for lunch, these things are my life, too. Maybe it’s because I never came to art with the expectation of any sort of enduring legacy, that conceiving of art, and therefore life, with such utilitarian efficiency doesn’t sit right. I’ve never cared what happens after I die — frankly, that’s none of my business — and if I am not focused on the ambition of having written a large number of great books which will be read long after my death, then these daily decisions are just as meaningful to me, and just as potentially delicious, as the words I get to choose in between.

If luck and talent lie outside your control, rigid routine isn’t for everyone, and hard graft might not pay off anyway, why do we turn to books about the creative life? Perhaps because it seems impossibly audacious, laughable even, to imagine leading a life as an artist, before we do it. Someone or something needs to suggest it is an outcome which could exist in material reality, whether through specific instruction or a more thoughtful, open-ended exposition of how one individual found their way. The real necessity for the aspiring artist is to feel that they are being granted permission.

Megan Nolan is the author of the novels “Acts of Desperation” and “Ordinary Human Failings”, Sally Mann’s “Art Work: On the Creative Life” is out now

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram