As part of her recent Janet Frame Memorial Lecture on the state of literature in New Zealand, Charlotte Grimshaw dwelt on a personal battle for authenticity, excerpted here.

This is the Janet Frame Memorial Lecture and here is a memory of Janet Frame. I remember visiting her house in a

small town, where we discovered Janet was dealing with her hypersensitivity to noise by barricading herself in, lining the internal walls.

Janet said to me, “You’re the one who used to think ‘Kathramansfield’ was all one word.” I was a teenager, and already I was thinking about translating the experience into fiction. I wanted to write about this strange, shy, charming Janet, the writer in the small, barricaded house in the silent street.

As we all know, Frame’s story involves what used to be called, colloquially, “madness”. And since this lecture pays tribute to her, it seems relevant to describe how, in this very building, in the Turnbull archive, my father CK Stead has lodged statements in which he asserts that I wrote my last book while suffering from “delusion” and “mental aberration”, which sounds to me a lot like “madness”.

This is a personal turn, but I’ll tell you why I think it’s relevant. In February, I was confronted with the kind of question the universe likes to throw at writers: how was I going to deliver the Janet Frame Memorial Lecture in the very building where I’d just found statements accusing me of delusion – and not mention the statements?

The universe answered the question: I had to mention them.

I began to write fiction as a child, and so very early on I was considering the process of fictionalising. If you were inventing a story about me, you might play with the idea that as the daughter of a fiction writer who used details of our lives in his stories, I became an unreliable narrator.

This would be fiction. In fact, every time I wrote, I was examining how to put reality through the fictional filter. This involved a continual evaluation. If I constantly had my eye on the border between fact and fiction, I knew it existed, and where it was.

I have lived my whole life on the front line of writing. I have confronted questions about truth, fictionalising, narrative and memory. I also, to my parents’ obvious discomfort, spent years noticing the ways they enforced various “truths”.

The Mirror Book. Photo / Supplied

I had resisted heavy paternal pressure to withdraw the book. CK wanted me to write instead, as he put it, a “celebratory” memoir. He had labelled me a “scolding fantasist”.

In January this year, I came across an online reference to family letters having been archived in the National Library. I asked CK about this. He told me the archive contained family emails, and he reassured me, repeatedly, not to worry about it, that “all your replies are in there”.

He said nothing about the statements he and my mother had lodged about The Mirror Book, to which there is no reply in the archive from me.

Something in his tone made me wonder, and I flew down to Wellington, accessed the archive and found what they’d done. Their statements assert that The Mirror Book is untrue, it is fiction and should be redesignated a novel.

I assume they did this secretly because to state publicly that The Mirror Book is untrue and a fiction that should be redesignated as a novel would be defamatory. Think of the controversy that blew up this year about the UK memoir The Salt Path, which turned out to be false. A false memoir is a fraud on the reader. It deserves to be, and often is, pulped.

CK’s Turnbull archive statement begins with him acknowledging that despite his having warned me that the book was no good (a “bad book”, he’d called it) and I would be irreparably damaged by it, I wasn’t.

He writes: “Some will think the critic Karl was wrong – the book has been a marked success, and is being talked about as the probable ‘Book of the Year’; but I don’t think I was wrong in that it could have been so much better if it had not been so fashionably self-pitying and self-congratulatory (especially about herself as a parent), and so ruthless on her own parents (particularly the mother) who are shown, even by the account itself, to have inflicted so little real harm.”

CK asserts that my memoir is a fiction and a fairy story. He writes: “In that fiction Kay [my mother] is the bad fairy, the wicked stepmother, while I am the bad, domineering Ruler (though also from time to time with the help of champagne a magical one), who torments and bosses around the sad Cinderella Charlotte.”

The Mirror Book was my account of growing up in a family that had a public face and a troubled private dynamic.

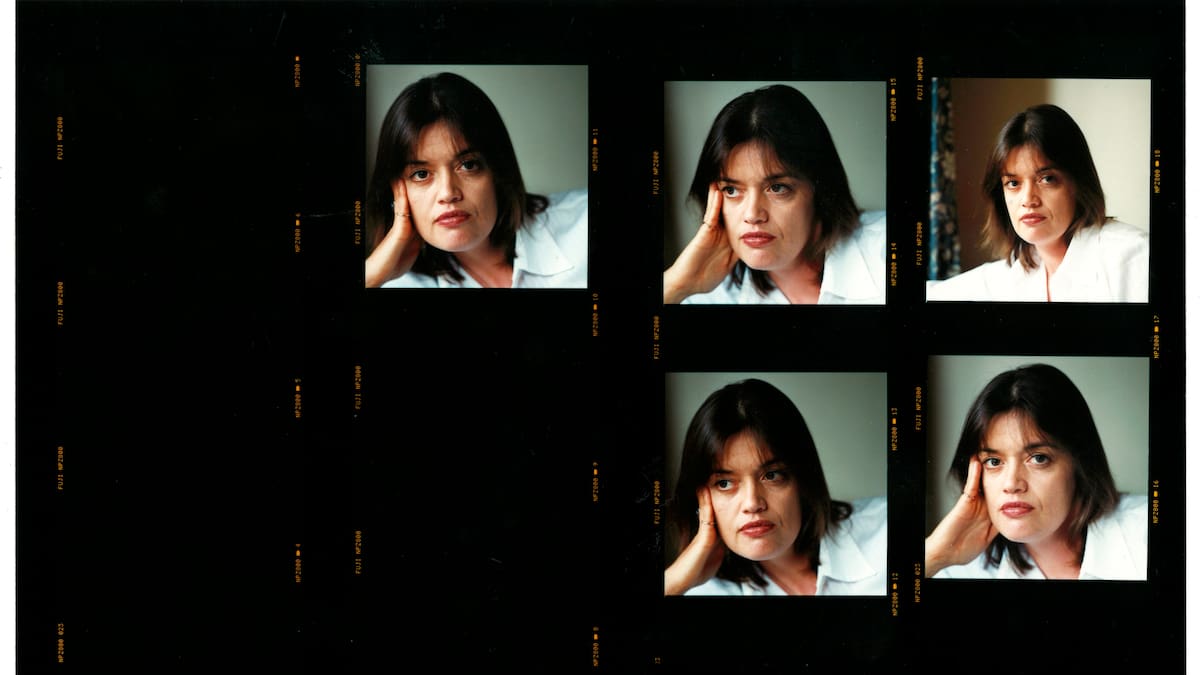

Charlotte Grimshaw

CK goes on, “I stress again the beauty of this fairy story, the genuineness of the pain it represents, the brilliance of the writing; but it should have acknowledged its own fictional nature and not presented itself as ‘truthful’.”

He describes my writing as “a mental aberration with no foundation in fact”, and a “delusion” on my part that had been “stoked by the psychotherapist”.

After referring to the writing of Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard as the literary fashion he says I was influenced by, CK writes: “But then if the aim was to show yourself as the victim (the one who by the currently prevailing ethic must never be rigorously questioned, doubted or disbelieved), you would need to leave out elements that mitigated the harm done to you. An unloving mother was, in the literary sense, more use to you than one such as Kay who was generous, good fun and always there to help when help was needed. So the real Kay had to become the fictional one.”

He doubles down on calling me a scolding fantasist. He states: “[Her father] asked her constantly, ‘Where is the girl who had such a clear sense of reality and its boundaries, and such a marvellous sense of humour – replaced by this scolding (as it seems to me) fantasist?’ Of course I asked that question. I’m asking it again now.

“All this is why I can simultaneously affirm that The Mirror Book is a beautiful work of art, and that it is not a truthful one. As a work of fiction it reveals Charlotte’s talent as clearly as anything she has written. But as a work of ‘non-fiction’ it is unjust and untrue.”

In addition to stating that The Mirror Book is “fiction” and a “delusion”, my father has “dealt with” and dismissed my description of being assaulted by a pool lifeguard when I was 13. (I’d written about being rather under-parented in the 80s.)

I mentioned in the memoir that if I’d complained, the lifeguard would have been charged. I wrote that my impression was that my parents wouldn’t have been interested. This is borne out in their Turnbull statements. Not only are they not interested, they’re disdainful.

Charlotte Grimshaw with her mother, Kay. Photo / Marti Friedlander

My mother expresses scorn for the Metoo movement and states: “Today the Queen’s Birthday honours are announced. Karl long ago received the highest of those for Services to Literature. In this season his own daughter has encouraged the world to ignore that honour and to dishonour him in the cause of sexual politics. Shame, I say. Forget silly old Literature; it’s marital probity and the protection of women we honour in 2021.”

CK writes: “It’s the kind of thing, as it was clearly meant to be, that catches the ear of the present moment. But my guess is that Charlotte made nothing of it at the time because there was nothing to be made. [The lifeguard] was fun, foolish and she could deal with him. She would not have wanted the fun spoiled or the harmless goof sanctioned. But years later he could loom into significance for Dr Sanders.”

CK never met the lifeguard he describes as a “harmless goof”, although he admits they knew about him. (What even is a goof?)

The lifeguard – in his 40s – wrote me love letters, that my parents saw, when I was 13. CK mentions, dismissively, “the pool was a crowded place”. (The closed first-aid room wasn’t crowded.)

Post memoir, they never asked me about it. This concept appears to be alien to them: the vulnerability of a 13-year-old girl. Even stranger is CK’s statement that my relationship at 13 with a 40-year-old was “fun”, the man was “harmless”, and I “could handle it”.

CK writes that I “wouldn’t have wanted the harmless goof sanctioned”. He is acknowledging there was something for which the goof could be sanctioned – for all the “fun” we were having.

There’s an uncomfortable echo with CK’s complaint that I had lost my sense of humour (of fun) and become “a scolding fantasist”.

[CK] describes my writing as ‘a mental aberration with no foundation in fact’, and a ‘delusion’.

Charlotte Grimshaw

These parents were my childhood advisers about sexual interest by middle-aged men. This was what I wrote about, quite calmly and cautiously I thought, in the memoir. There were a lot of things they felt I could handle back before I lost my sense of fun.

Turning to my consulting of a psychotherapist, CK dismisses entirely the disciplines of psychology and psychiatry, citing a single memoir by a Sunday Times journalist, Oliver Kamm, who tried therapy and found it didn’t help him with clinical depression. (This same journalist can be found online historically approving of the war in Iraq.)

CK writes: “This, I suspect, is where ‘Dr Marie Sanders’ was invaluable. Psychotherapists of the post-Freudian stamp like to find a mother or father, or a sibling, aunt or uncle, who was the up-to-now unrecognised source of your trouble. Oliver Kamm in his book Mending the Mind (pp134-43) describes how a psychotherapist tried to cure his serious, indeed disabling, depression by reaching back into his past – with results that were worse than useless, briefly damaging … Fortunately Kamm recognised the mistake soon enough to escape into other treatments involving partly the right kind of drugs … and partly the conscious alteration of certain habits of mind.”

CK’s statement goes on: “If ‘Dr Sanders’ had recommended regular attempts to remember the good things (which were innumerable) about Charlotte’s relations with her mother we might have had the better book that is buried within the published one.”

In her statement, my mother also cites Kamm’s book. She states that I – Charlotte – suffer from “depressive illness” which she says the psychologist has been “unable to cure”. This is false and defamatory. As Kay knew, I have never in my life suffered from depression.

My mother writes that it was untrue to describe her as upset by CK’s affairs. She says she wasn’t bothered by them, and she’s sure they gave him “a lot of friendship and fun”.

Karl and Kay Stead and Charlotte Grimshaw at the family home in Parnell, Auckland, c2017. Photo / Supplied

It is baffling how unnecessary it is. Why would parents seek to deny a daughter’s personal story in this way? It’s bizarre and strange.

It has also been described to me as “cruel”. And it is. It sure is cruel.

You could say his (and Kay’s) instinct is autocratic. And anti-democratic and effectively anti-intellectual. It certainly doesn’t strike me as intellectually good enough.

CK’s stance also seems aesthetically questionable. A purely “celebratory” portrait of a family must be inauthentic. Human life is not black and white; it’s infinitely contradictory and untidy and that’s why it’s interesting. We try to portray it and our attempt is always imperfect. We aim for authenticity by making the best representation we can, and also by acknowledging what we don’t know.

In my opinion his demand for a “celebratory” portrait puts CK on the side of bad art. It’s a stand against open discourse, which is a social good.

It’s also an amazing nerve, given just how censored my memoir was.

What was my reaction to this? The most obvious word to reach for is anger. But anger tends to diminish the capacity for reasoning. So I decided to take a step back, not to confront. I’ve said nothing about it and gone on being a dutiful and kind daughter to the best of my ability.

In my imagination, though, I went back to that tiny house in the silent long-ago street, knocked on the door, and consulted the ghost of Janet Frame.

What do you do when people call you “delusional”? You write. The answer to the anger, to the intellectual problem of the Turnbull archive, and to the accusation of being delusional, is writing.

Charlotte Grimshaw: “We don’t want ‘celebratory’ hagiographies by robotic enablers. At least I hope we don’t.” Photo / Supplied

I’m not dismissing the value of anger. Given the atmosphere of oppression in the world, it’s time to fight back and make some good trouble. We need to defend the individual against non-empathisers everywhere, whether they are tech companies or robots, political tyrants or petty ones.

My father’s dismissal of my memoir and his defamatory assertion that it’s “fiction” and a “delusion” is the kind of attempt at control I found elsewhere in the Turnbull archive. I came across a letter in which he instructs me to make sure I tell interviewers that the characters in my 2018 novel Mazarine “are not autobiographical”.

I should note that I haven’t set about asserting that CK’s three autobiographies are untrue works of fiction. Nor that he is “mad”.

He could have shrugged and said, “Sure, it was the 80s, we were preoccupied; we probably weren’t great parents. Fair enough, tell your story.”

It is notable that CK has wanted to discredit the work not of a stranger but of his own daughter. Objectively it seems extreme.

So the Turnbull archive now records that The Mirror Book is the untrue delusional product of mental aberration and uncured depressive illness; it is fantasy and a fiction. The Mirror Book is fake news.

I suggested that the family imposed a regime in which we were not invited to be our authentic selves. If they hadn’t archived these statements, they wouldn’t have confirmed my theory in the emphatic way they have. This seems poignant to me.

The Mirror Book is not fiction. It was vetted by a specialist QC and is litigation-proof because everything in it is true. I published it to try to make them understand my experiences. This turned out to be a vain hope, but it was sincere.

If they had publicly challenged my account, they would have opened themselves up to discussion of more extreme, true family details. They appear to have arranged it so they could defame me without sanction. They believed that my life was exclusively “their story to tell”.

Reading the statements, I’m struck by their unified disdain. I hadn’t expected this. We all have an irrational hope that our voice will be heard (the voice of that 13-year-old girl, perhaps). Writing, we are trying to make ourselves understood.

The irony is worth recording. CK has always been a public intellectual and often a contrarian, yet here he shows no tolerance for dissent. He has championed intellectual rigour yet appears to be demanding that I express myself only in platitudes.

What do we value when we love an author’s work? We love their voice. If we enjoy novels by, say, Catherine Chidgey or Elizabeth Knox or Eleanor Catton – or by CK Stead – it’s because we love the author’s uniqueness. We queue up for them because we want that author, the real thing. We don’t want a mash-up churned out by AI. We don’t want “celebratory” hagiographies by robotic enablers, either. At least I hope we don’t. That will not do at all.

I’ve described what I discovered in the Turnbull Archive because it’s a complicated human story and that’s what I want to champion. In its own minor way it is a tragedy. It’s an epilogue to a theme of The Mirror Book: the family as a microcosm, where a domineering force just will not stop trying to control what it does not like.

The microcosm expands out into the world, and the forces we’re up against have the same characteristics. We are sentient individuals with rights. In standing up for those rights we act for our collective good.

The state of the literary nation may be troubled, but let’s be optimistic about New Zealand writing. We need to defend it and keep it human.

Remembering the great Janet Frame, let us celebrate our unique New Zealand voices. And let us each value our own authentic understanding of “celebratory”.

Charlotte Grimshaw delivered the 2025 Janet Frame Memorial Lecture at the National Library in Wellington on October 14.

SaveShare this article

Reminder, this is a Premium article and requires a subscription to read.

Copy LinkEmailFacebookTwitter/XLinkedInReddit