Characteristics of participants

The characteristics of the 28 participants are provided in Table 2. They had an average age of 36.1 years (range: 27.0–45.0), with 9.1 years of work experience (range: 1.0–17.0), including 7.1 years in HD (range: 1.0–17.0). Among them, 64.3% were female, 75.0% held a master’s degree, and 57.1% had an intermediate professional title. Furthermore, 89.3% indicated that their institutions lacked regular ethics training programs for clinical practice.

Table 2 Description of participants (N = 28)Ethical challenges in HD practice

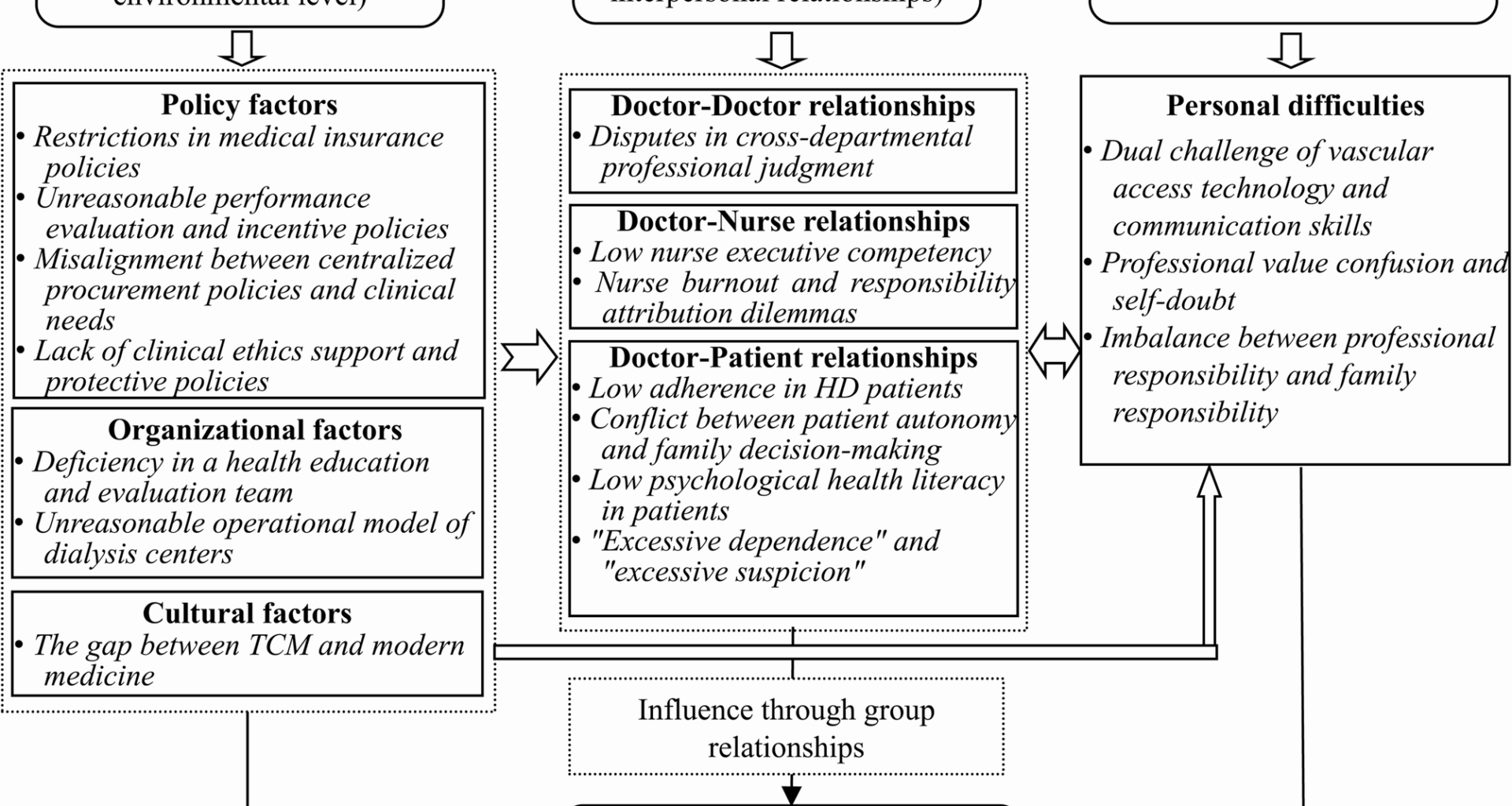

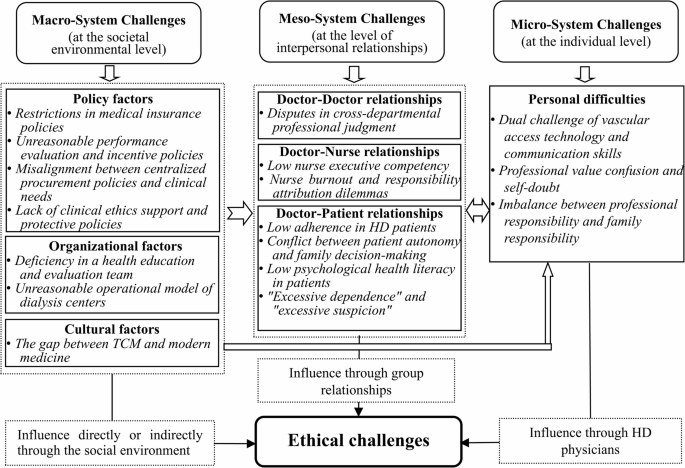

Through phenomenological analysis, we identified 78 initial codes related to ethical challenges in HD practice. These codes were systematically organized into 17 subcategories, which were further grouped into seven subthemes under three main themes. As shown in Fig. 1, challenges were identified across three levels: macro-level factors encompassing policy, organizational, and cultural dimensions; meso-level interactions among healthcare providers and patients; and micro-level individual struggles. These levels demonstrated interconnected influences, with macro-level factors shaping meso-level dynamics that subsequently affect individual struggles. Furthermore, direct interactions existed between macro- and micro-levels, while micro-level factors reciprocally influenced meso-level interactions.

The model addressing the ethical challenges for HD physicians

Theme 1: Macro-system challenges (at the societal environmental level)

Factors such as policies, organization, and culture were categorized under the macro-system, representing societal environmental elements.

Subtheme 1: policy factors

Subcategory 1: restrictions in medical insurance policies

Medical insurance policies were a significant limiting factor mentioned in all interviews. A conflict existed between the reimbursement limits set by insurance policies and physicians’ treatment decisions. The current reimbursement cap for HD patients was lower than their actual expenses, leading some patients to request a reduction in HD frequency. Moreover, the criteria for insurance coverage were considered unreasonable. One group pointed out that, patients were only eligible for reimbursement of the costs of relevant therapeutic drugs when specific laboratory indicators were abnormal, despite the fact that it was the use of these drugs that maintained the normal levels, causing confusion among physicians. Furthermore, insurance policies varied by region and patient identity, which some participants perceived as a violation of treatment fairness.

“Many patients exceed the annual insurance reimbursement limit and request for reduction in HD frequency and medication dosage, putting us in a difficult position.” (FG1-Physician 3: female, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

“For instance, patients maintain normal hemoglobin levels due to erythropoietin treatment. However, once the levels are normal, insurance no longer covers erythropoietin.” (FG4-Physician 6: female, senior professional title, 16 years in HD).

“Different regions, hospitals, and patient categories have different reimbursement rates, which is unfair to patients and may lead to misunderstandings between doctors and patients.” (FG2-Physician 1: male, senior professional title, 17 years in HD).

Subcategory 2: unreasonable performance evaluation and incentive policies

Participants expressed a prevalent dissatisfaction regarding the application of uniform performance evaluation criteria across different medical specialties. They were assessed based on the utilization rate of both Chinese medicine and TCM techniques. However, ESRD patients rely more on dialysis technology and Western medicine, making this evaluation system unsuitable. The physicians also expressed that they should rotate within nephrology rather than being fixed in dialysis units, as a fixed-position system has limited their ability to develop comprehensive clinical skills.

“Physicians in HD units, interacting with the same patient population, and addressing similar clinical issues, will gradually lose their capacity for critical thinking and innovation, leading to a sense of complacency or burnout.” (S1: female, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

“Administrators implement a uniform policy for assessing the application of TCM across all medical specialties, with the evaluation results influencing physicians’ income—a practice we deem to be unjustifiable.” (FG4-Physician 6: female, senior professional title, 16 years in HD).

Subcategory 3: misalignment between centralized procurement policies and clinical needs

Physicians mentioned that centralized procurement policies failed to meet the individualized needs of HD patients. Hospitals typically prioritized high-volume, widely applicable products in procurement, making it difficult to include specialized drugs and medical supplies for certain patients. This restricted patient choice and limited physicians’ ability to provide precise and comprehensive care. Patients requiring specific medications had to obtain them from outside the hospitals, leading to inconvenience and a decline in trust towards their physicians.

“Centralized procurement policies restrict us from selecting personalized HD filters, preventing optimal HD outcomes.” (S1: female, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

“Institutions have discontinued the provision of previously approved medications, compelling patients to procure them from external pharmacies. This situation has led some patients to suspect that we have financial affiliations with these pharmacies.” (FG2-Physician 2: female, intermediate professional title, 7 years in HD).

Subcategory 4: lack of clinical ethics support and protective policies

While all participating hospitals had formally constituted institutional ethics committees, none demonstrated adequate fulfillment of their mandate to provide substantive guidance on clinical ethics dilemmas. Additionally, there was a lack of systematic training in clinical ethics for physicians, leaving them feeling helpless when faced with ethical issues. Participants also reported that many HD patients exhibited abnormal psychological states and occasionally engaged in aggressive behavior towards them. However, protective policies for HD physicians were notably absent in such situations.

“Hospital regulations primarily constrain medical staff but do not include measures to protect us.” (FG4-Physician 1: male, junior professional title, 6 years in HD).

“Compared to other patients, HD patients have special needs, but we doctor lack training and guidance on how to respond ethically.” (FG2-Physician 4: male, junior professional title, 2 years in HD).

Subtheme 2: organizational factors

Subcategory 1: deficiency in a health education and evaluation team

Participants mentioned that the education on HD was highly homogenized, without personalized and stratified education based on factors such as patient age, gender, and education level. Additionally, it was predominantly text-based, poor in varied and interactive methods. There was also an absence of a feedback mechanism for evaluating the effectiveness of education, no established stratified assessment system, and shortage of dynamic tracking and evaluation of its outcomes. They believed that a professional HD education team might be able to resolve these issues.

“The textual materials are outdated, and all patients receive the same content. An education team should be established.” (FG2-Physician 3: female, junior professional title, 3 years in HD).

“Yes, and the effectiveness of education should also be evaluated, such as using a scale to test elderly patients’ memory retention. Otherwise, the education becomes meaningless.” (FG2-Physician 1: male, senior professional title, 17 years in HD).

Subcategory 2: unreasonable operational model of HD centers

Interviews revealed that many HD centers exhibited deficiencies in interdisciplinary collaboration and resource integration, with a disconnect between their operational models and service delivery frameworks. These centers provided services for outpatients, yet they adopted an inpatient operational model. Physicians also highlighted that patients often presented with multiple comorbid conditions. However, the current scenario was marked by the absence of multidisciplinary team (MDT), which might result in a lack of comprehensive and coordinated treatment plans during the course of therapy.

“The HD center serves outpatients, but it conducts cost-effectiveness according to the inpatient model, which is an erroneous operational approach.” (FG4-Physician 6: female, senior professional title, 16 years in HD).

“Patients commonly present with multiple comorbidities affecting the cardiovascular, endocrine, and urological systems, among other organ systems. However, the dearth of a MDT undermines the development of comprehensive treatment strategies.” (FG2-Physician 4: male, junior professional title, 2 years in HD).

Subtheme 3: cultural factors

Subcategory: the gap between TCM and modern medicine

Participants reported that the scope of TCM was constrained by the divergence between its theoretical framework and modern medicine. This theoretical gap limited TCM’s application in HD patients. For instance, herbal decoctions, a quintessential TCM treatment, were often incompatible with patients’ fluid management protocols, rendering them unusable. Although TCM techniques such as acupuncture could assist patients in alleviating certain complications and comorbidities, their effectiveness in improving renal function was not significant, which posed a dilemma for HD physicians.

“This is an awkward situation for us. We can only use acupuncture and fumigation therapy to alleviate HD side effects, but we have no effective TCM treatment to improve renal function of HD patients.’’ (FG3-Physician 1: male, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

“TCM decoctions have a certain effect on balancing the yin and yang of HD patients and can enhance their immunity. However, due to the patients’ strict fluid intake restrictions, they cannot be administered.” (S4: female, intermediate professional title, 7 years in HD).

Theme 2: Meso-system challenges (at the level of interpersonal relationships)

Interprofessional dynamics, particularly doctor-doctor, doctor-nurse, and doctor-patient relationships were categorized under the meso-system, which pertained to the level of interpersonal relationships.

Subtheme 1: doctor-doctor relationships

Subcategory: disputes in cross-departmental professional judgment

Doctors from different specialties often had differing opinions regarding disease assessment and treatment plans. HD physicians prioritized renal replacement therapy and complication management for ESRD, while physicians from other specialties focused on different aspects of care. When patients received inconsistent medical advice, they might question the physicians’ professionalism, thus shaking their trust in the medical team. Since HD patients frequently required consultations due to complications, they were more prone to receiving varied treatment suggestions, leading to a coordination dilemma for HD physicians.

“Cardiologists recommend restricting the rate of fluid removal during HD to reduce cardiac burden, while we believe that adequate fluid removal is key to relieving volume overload, which often leads to disagreements in treatment recommendations.” (FG4-Physician 2: male, intermediate professional title, 8 years in HD).

“Due to differences in professional expertise and areas of focus, doctors from different departments may have varying assessments of the patients’ conditions, which may affect patients’ trust in us.” (FG1-Physician 4: female, intermediate professional title, 5 years in HD).

Subtheme 2: doctor-nurse relationships

Subcategory 1: low nurse executive competency

Physicians found the low executive competency of nurses to be a frustrating issue. Given the highly specialized nature of HD care, some nurses, owing to their insufficient clinical experience and weaker team consciousness, increased obstacles in doctor-nurse collaboration. Physicians were particularly concerned by nurses’ tendency to defer management of HD-associated abnormalities to physicians rather than addressing issues proactively. They attributed this to a lack of responsibility or low executive competency among nurses, leaving physicians physically and mentally exhausted.

“We ordered a stat blood glucose check, but when the results still hadn’t come back after ages, we ended up doing it ourselves to adjust treatment – really frustrating how slow the nurses were.” (FG3-Physician 7: female, intermediate professional title, 10 years in HD).

“The nurse keeps calling me every three minutes for matters like dialysis machine alarms or clotting in the tubing. It’s absolutely infuriating.” (FG4-Physician 4: female, intermediate professional title, 5 years in HD).

Subcategory 2: nurse burnout and responsibility attribution dilemmas

The interviews revealed a significant level of burnout among senior nurses, substantially compromising the efficiency of collaboration between nursing staff and physicians. New physicians, due to their junior status, were forced to take on tasks that do not belong to them, leading to the dilemma of experienced nurses’ empiricism and junior doctors’ obedience. Additionally, ambiguous job responsibilities led to conflicts between nurses and physicians in vague work areas, embodying the dilemma of responsibility attribution.

“Senior nurses lack enthusiasm for learning new techniques and prefer relying on habitual thinking, making doctor-nurse collaboration more challenging.” (FG3-Physician 6: male, intermediate professional title, 4 years in HD).

“When I first started working, senior nurses frequently ordered me around. As a junior staff member, I didn’t dare to refuse.” (S4: female, intermediate professional title, 7 years in HD)

“There are no clear regulations on whether tasks like blood sampling and health education fall under medical or nursing responsibilities, which frequently leads to conflicts between nurses and us.” (FG2-Physician 3: female, junior professional title, 3 years in HD)

Subtheme 3: doctor-patient relationships

Subcategory 1: low adherence in HD patients

Poor patient adherence represented the most formidable challenge confronting participants, with non-compliance primarily manifested in dietary and fluid intake mismanagement, coupled with outright refusal of routine medical examinations. This issue was particularly pronounced among individuals with extended dialysis vintage or geriatric population, who frequently displayed a dismissive attitude toward clinical recommendations. Certain patients misattributed therapeutic stagnation to inherent flaws in the prescribed regimen rather than acknowledge compliance deficits. This cognitive dissonance created an ethically charged impasse for attending physicians.

“Patients fail to follow dietary and fluid restrictions, leading to worsened conditions, yet they shift the blame onto physicians and vent their dissatisfaction at us.” (FG4-Physician 3: female, intermediate professional title, 8 years in HD).

“Long-term dialysis patients or elderly patients, often obstinate with cognitive biases about HD, demand physician adherence to their self-prescribed treatment parameters, such as fluid removal targets or dry weight determination, posing challenges for us.” (S5: female, senior professional title, 14 years in HD).

“During dialysis, we noticed some patients were close to shock, but they resisted undergoing an electrocardiogram, or stopping dialysis, despite our recommendations.” (FG3-Physician 6: male, intermediate professional title, 4 years in HD).

“Some diabetic HD patients consume sugary drinks, while others excess high-potassium fruits, complicating treatment planning.” (FG1-Physician 1: female, senior professional title, 5 years in HD).

Subcategory 2: conflict between patient autonomy and family decision-making

This conflict manifested in two distinct scenarios: when patients wished to continue HD while their families advocated for treatment discontinuation; and when patients refused HD but their families insisted on its continuation. These situations underscored the complexity of the ‘who decides’ dilemma in medical decision-making. Interviews revealed that family members often became the de facto decision-makers due to their control of financial resources or legal authority. This contradiction not only placed physicians in dilemmas but also challenged patient dignity and the right to self-determination. Physicians frequently expressed discomfort when confronted with such patient-family decision-making conflicts.

“A diabetic kidney patient wanted to keep getting dialysis, but his family pulled the plug thinking it was pointless, leaving him with no say at all.” (FG3-Physician 2: female, junior professional title, 1 years in HD).

“Patients should have the final say, but let’s be real – families usually call the shots because they hold the purse strings, especially in rural areas where insurance is spotty.” (FG2-Physician 1: male, senior professional title, 17 years in HD).

“One patient couldn’t tolerate HD – kept going into atrial fibrillation and acute hypotension every session. He wanted to stop because it was torture, but the family pushed to continue. Is this really love, or just making things worse?” (FG1-Physician 4: female, intermediate professional title, 5 years in HD).

Subcategory 3: low psychological health literacy in patients

HD patients generally demonstrated low psychological health literacy, with many experiencing psychological issues including anxiety, depression, manic episodes, and even aggressive behaviors. This situation placed the physicians in a dual ethical dilemma: they struggled to balance ‘life-first’ medical principles with irrational patient behaviors, torn between treatment obligations and self-protection. When patients demanded special privileges, it created a conflict between the principles of fairness and the need for empathy. Most hospitals did not provide psychological interventions for HD patients, which seemed to be more a result of patients’ internalized stigma about their illness, leading to resistance to psychological assistance.

“Patients, due to psychological or personality reasons, sometimes verbally or even physically attack us, which makes us both angry and fearful.” (FG4-Physician 6: female, senior professional title, 16 years in HD).

“Some patients come for HD outside of the scheduled time and demand various privileges: priority dialysis, specified nurses, specified dialysis machines, and even specified beds, making other patients have similar demands and causing confusion.” (S5: female, senior professional title, 14 years in HD).

“We didn’t provide professional psychological intervention for patients because they didn’t believe they had psychological issues.” (S1: female, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

Subcategory 4: “excessive dependence” and “excessive suspicion”

HD patients exhibited excessive dependency, manifested as their insistence on receiving treatment exclusively from their designated physician, implicitly negating the professional competence of other physicians. This dependency further presented as patients perceiving dialysis as a ‘reset button’, anticipating complete restoration of health post-treatment, thereby imposing additional psychological burdens on physicians. Concurrently, excessive suspicion was observed, characterized by patients’ misinterpretation of medical intentions and concealment of medical histories, reflecting distrust towards the physicians. Physicians must respond to the individualized needs of patients while maintaining the fairness of medical principles, and may even have to develop medical plans based on incorrect information provided by the patients, presenting significant challenges.

“Certain patients specify that only I can provide medical services for them. This not only increases my workload but also disrupts the harmonious professional relationships with my colleagues.” (FG3-Physician 1: male, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

“I can’t work with patients who hide their medical history or diet habits, as it leads to design incorrect treatment plans.” (FG1-Physician 2: female, intermediate professional title, 5 years in HD).

“Patients held unrealistically high expectations regarding treatment outcomes, anticipating a complete restoration of normal physiological functions following therapy, which imposed significant psychological stress on me” (FG2-Physician 1: male, senior professional title, 17 years in HD).

Theme 3: Micro-system challenges (at the individual level)

Micro-system challenges encompassed personal difficulties physicians encountered in their skills, ambivalence, and an imbalance of responsibilities.

Subtheme: personal difficulties

Subcategory 1: dual challenge of vascular access technology and communication skills

The interviewees identified vascular access management as a significant clinical challenge. The complexity and high-risk nature of access maintenance and repair procedures, compounded by experience barriers, have induced professional anxiety among junior physicians. Another challenge lay in communication skills. Physicians faced multiple barriers: patients with limited health literacy struggled to understand medical explanations, while paranoid patients often rejected rational communication. These communication breakdowns often exacerbated physicians’ sense of professional frustration.

“I am most concerned about vascular access issues, especially recurrent thrombosis in arteriovenous fistulas among diabetic HD patients. This anxiety often affects my sleep, causing dreams of emergency thrombectomies and waking up in sweat.” (S1: female, senior professional title, 10 years in HD).

“Particularly with patients lacking medical literacy, effective information transfer often proves unattainable, leaving me feeling frustrated.” (S5: female, senior professional title, 14 years in HD).

Subcategory 2: professional value confusion and self-doubt

The participants often established enduring relationships with patients. Prolonged exposure to HD patients’ suffering and mortality rates, the physicians were prone to empathy for patients’ negative emotions, indirectly shouldering their suffering. The limited therapeutic efficacy in HD management induced professional disempowerment and vocational identity crises among physicians, and was further exacerbated by the observed disparity between their substantial emotional investment and suboptimal treatment outcomes, prompting them to question both their clinical competence and career choices.

“Even though I have done my best, most patients still end up weakening or dying, leading to feelings of frustration and making me question my career choice.” (FG3-Physician 5: female, intermediate professional title, 8 years in HD).

“When facing terminal HD patients, witnessing the pain they endure, I start to question whether I have the ability to save lives. That pain is unbearable.” (S3: male, intermediate professional title, 3 years in HD).

Subcategory 3: imbalance between professional responsibility and family responsibility

Professional obligations frequently carried over physicians’ work-related stress into their personal lives, impairing family engagement and generating feelings of guilt. The unique demands of HD practice prevented physicians from maintaining the regular work schedules and rest periods typical of other medical specialties, resulting in blurring of boundaries between professional responsibilities and personal life. These circumstances engendered emotional conflicts among physicians: professional obligations necessitated complete occupational commitment, while familial guilt imposed psychological distress.

“Work-related stress often triggers a surge of negative emotions, which I unconsciously project onto my family members. This unintentional emotional transference fills me with profound guilt.” (S5: female, senior professional title, 14 years in HD).

“While physicians in other specialties enjoy scheduled holidays, we dialysis physicians are perpetually on-call, deprived of holiday breaks and quality time with our families.” (S2: male, intermediate professional title, 5 years in HD).