The study received ethical approval from the German Association for Experimental Economic Research e.V. (No. KEF58hmh, https://gfew.de/ethik/KEF58hmh). We obtained electronic informed consent from all participants. Data collection occurred via Prolific (https://www.prolific.com, Prolific, 2025) in July and August 2024, involving 20,013 participants with complete data entries, all residing in Europe or holding European nationality. Altogether data was collected from 21,312 individuals including missing data. All participants answered the same set of survey questions, which were translated into Greek, Dutch, Portuguese, German, and Turkish. The survey, designed using LimeSurvey (https://www.limesurvey.org, LimeSurvey, 2025), was distributed through Prolific. The resulting dataset, provided in an Excel file, includes all survey items and responses.

Methodological approach

The questionnaire was designed to explore the socioeconomic and spatial effects of remote working arrangements across Europe, with a focus on understanding working and living conditions, employment dynamics, and quality of life. Its development followed a structured, multi-step process:

1.

Literature Review. Initial desk research examined existing studies and reports on the implications of remote work, including effects on work-life balance, occupational health, employment formats, spatial implications and socioeconomic outcomes.

2.

Co-Creation. In line with recommendations from the literature (e.g., Dillman et al.20) the questionnaire items were formulated collaboratively among 27 experts in socioeconomic research, urban studies, and occupational health. Statements employed Likert scales and were designed to present balanced perspectives to minimize response biases. Spatial and demographic dimensions were also incorporated.

3.

Translation. We translated the survey into five languages—Turkish, Greek, German, Portuguese, and Dutch—with the assistance of ChatGPT (https://chat.openai.com, OpenAI, 2025). The translations were refined through a back-and-forth process within the author team to ensure comprehension, clarity, accuracy and consistency.

4.

Ethical and Legal Considerations. To ensure compliance with GDPR standards and safeguard participant anonymity, the survey excluded personally identifiable information while retaining georeferenced data for regional and spatial analysis. Although we initially requested information on the municipalities of participants’ work and residence to determine whether their location was rural or urban, this data was later deleted. We obtained electronic informed consent from all participants for the publication of anonymized data.

5.

Pilot Testing. A trial run with 45 respondents was conducted to evaluate question clarity, identify technical issues, and refine the instrument based on participant feedback.

The finalized questionnaire comprises 24 structured questions, corresponding to the three thematic areas outlined in the first section of this paper, and further detailed in the section on Variables.

Data collection

Data were collected in July and August 2024 using LimeSurvey as the survey platform and Prolific for participant recruitment. Participant recruitment on Prolific was based on the following criteria: (1) Geographical Representation: Distribution across countries in the European Union (including the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Turkey) proportionate to their 2023 populations, (2) Gender Parity: Equal gender distribution within each country, and (3) Age Targeting: Targeting the mean age per country through simple random sampling. 21,312 responses were collected during this period whereas 20,013 provide complete dataset. A total of 299 responses were removed due to incompleteness. Participants responded to identical survey items in their preferred language.

Variables

This section presents the individual survey questions into the three initial thematic areas: (i) perceptions and experience of remote work, (ii) spatial factors, relocation practices and mobility patterns and (iii) demographics and employment context.

For the first thematic area, perceptions and experience of remote work, 24 questions provides insights to eight variables. We used a Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) to measure each individual’s level of agreement with the following statements:

(1)

It is important for me to have the flexibility to choose my work location;

(2)

Remote work positively impacts my personal life;

(3)

It is important for me to adjust my work schedule based on personal circumstances;

(4)

I prefer remote work over in-office work;

(5)

Remote work negatively impacts my career advancement (promotion, recognition, skill development);

(6)

I find it difficult to maintain a healthy work-life balance while working remotely;

(7)

I find remote work more challenging than in-office work (e.g., isolation, more distractions, time zone differences);

(8)

I feel less productive while working remotely (more distractions, no focus, bad time management, etc.).

The answers to these statements provided a holistic understanding of the needs and the perceptions of individual regarding the versatile implications on flexibility, remote working benefits, adjustment to personal circumstances, remote work preferences, negative impact, well-being, challenges, and productivity.

For the second and third themes of the questionnaire, we employ mixed response formats tailored to each variable’s context and dimensions. These include yes/no questions to assess binary outcomes and ask more questions, multiple-choice questions to capture diverse options, single-choice questions for prioritization or preference, and importance ratings to evaluate the significance attributed to specific factors. This approach ensured flexibility and precision in capturing the multifaceted dimensions of the phenomenon across the following variables:

(1)

On average, what amount of time of your weekly work schedule do you perform remotely/ in the office?

(2)

When working remotely, do you currently have access to the following amenities within a 15-minute walk;

(3)

Have you changed your place of living and/or working due to favourable remote working arrangements since 2020?

(4)

Name the 5 most important reasons that led to your place of living relocation;

(5)

How much time do you spend on commuting to work and how do you usually commute to work.

For the demographics, the variables included, (1) gender, (2) age, (3) time spend in education, (4) time spend in professional working, (5) place of residence, (6) place of work, (7) industry sector, and (8) employment status.

Following is a description of the individual survey questions per theme.

Perceptions and experience of remote work

Perceived flexibility

To explore the concept of perceived flexibility, the survey included the item “It is important for me to have the flexibility to choose my work location.”. Workplace flexibility refers to “the ability of workers to make choices influencing when, where, and for how long they engage in work-related tasks.” (Hill et al.21, p. 152). Such flexibility embodies a reciprocal trust and respect between employer and employee, or between supervisors and their reports, and relies on a supportive organisational culture that grants individuals’ substantial autonomy over their roles and working conditions22. Hence, perceived flexibility links to notions of overall employee job satisfaction, engagement and, ultimately, retention23. This is also particularly true in relation to the young generation, which prizes workforce flexibility much more than older generations leading to a remarkable positive impact on employee engagement24. Studies have shown that in recent years flexibility in relation to location and work schedule has been increasingly considered to be two of the main parameters that define the quality of employment, alongside career opportunities and income. Flexibility has been found to correlate positively with job satisfaction and organizational commitment while at the same time, it correlates negatively with exit intentions.

Marx et al.25, for instance, confirmed in their study that providing employees with the choice of home-based teleworking correlated negatively with voluntary employee exit. Additional studies provide further evidence of applicant attraction when time/spatial flexibility is offered26. When it comes to overall job satisfaction, Bjärntoft et al.27 identified in their study that perceived flexibility positively associated with work-life balance and in many cases mitigated the negative effects of remote working, such as over-commitment to work and high job demands.

Transitioning from the broader benefits, challenges, and implications of remote work to the specific dynamics of participants’ working arrangements, respondents were asked to quantify their weekly division of hours between remote and in-office work. Subsequently, participants selected their preferred location for remote work from three options: (1) the home, (2) a third place (libraries, cafes, community buildings, etc.) and (3) a co-working space. For those preferring third places or co-working spaces, they were asked to indicate by choosing yes or no if their preference was linked to (1) the availability of car parking, (2) the accessibility via public transport and (3) its proximity within walking or cycling distance from home. This section of questions aimed to provide an understanding of participants’ remote work arrangements.

Remote work benefits

The benefits of remote work were examined through the survey item “Remote work positively impacts my personal life.”. The advantages of remote work are intrinsically linked to work-life balance and well-being, which is a multilayered topic. Remote work has had both positive and negative correlations with work-life balance, especially in relation to healthy and sustainable boundaries, burnout, impact on retention and productivity. For example, Ferreira and Gomes28 conducted a study across European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, which demonstrated a strong association between individual and organizational resources and the achievement of work–life balance. Conversely, a study by Buonomo et al.29 found no significant direct or indirect link between leader support and well-being but rather highlighted the importance of strong social connections as a major factor in employee well-being. Additionally, Sandoval-Reyes30 introduced another dimension to work-life balance by discussing gender asymmetries in married couples, such as uneven distribution of childcare and home care responsibilities, showcasing an example of inequality that can determine the impact of remote work on employees’ personal life.

Adjustment to personal circumstances

The ability to adapt work schedules to personal circumstances was assessed through the survey item “It is important for me to adjust my work schedule based on personal circumstances.”. This concept is closely related to work-life balance, flexibility and autonomy, all of which play a pivotal role in shaping modern workplace dynamics. Research underscores the value of non-monetary policies, such as flexible working hours, in prompting work life balance. The importance of flexibility in remote work is furthered highlighted by calls to include more ‘inclusive flexibility’ in workplace policies31. For instance, remote working options could potentially become more inclusive for groups of people with chronic illnesses, who would otherwise be less employable. To this end, a study by Vanajan et al.32 on older workers experiencing long-term health issues showed that flexible work hours have a positive impact on their ability to work. Additionally, remote work policies could help companies overcome regional talent acquisition challenges as it enlarges the pool of potential employees by offering time-flexible location-independent employment33.

Remote work preferences

The preference for remote work over in-office arrangements was assessed through the survey item “I prefer remote work over in-office work.”. This concept is intrinsically linked to autonomy, time and spatial flexibility and communication. Research on time and spatial flexibility has yield mixed findings regarding its impacts on work-life balance and performance. Metselaar et al.34 showcased that autonomy, i.e. the freedom of the employee to determine when and where to work, has a direct positive correlation with employee performance. Similarly, Wheatley et al.31 emphasized the importance of ‘inclusive flexibility’ and ‘responsible autonomy’ in organizational policies. These approaches advocate for tailoring remote work policies on the individual needs of the employees, while employees would be accountable for the responsible use of their work autonomy.

Employee preferences for remote or in-office work, particularly within hybrid work models, often depend on the type of tasks involved. For instance, tasks requiring deep concentration might be more suited to remote work as opposed to those requiring communication. Jämsen et al.35 highlighted that effective communication can be challenging in remote settings, making employees in communication-based tasks, such as managers, more likely to prefer in-office environments. These findings underline that when autonomy can be exercised, discrepancies in preferences can be found across different industries or company roles.

Negative impact on career advancement

The potential negative impact of remote work on career advancement was assessed through the survey item “Remote work negatively impacts my career advancement (promotion, recognition, skill development).”36. Τhis issue has been widely discussed in media articles of general interest, in public forums and groups dedicated to remote workers, often framed with the “out of sight, out of mind” narrative (Countouris & De Stefano37, p. 147). While it may be premature to draw definitive conclusions, several studies in relevant literature have begun to examine this issue. For example, Emanuel et al.38 investigated the effect of physical proximity among software engineers at a Fortune 500 online retailer. Their findings indicate that proximity encourages junior engineers to seek and receive more feedback and ask more follow-up questions, while female engineers participate more actively in feedback exchanges38. The impact of proximity does not immediately translate to career advancement38. Initially, junior engineers experience modest opportunities for pay raises. However, over time, the human capital developed through close mentorship becomes evident, often resulting in more substantial pay increases and, in many cases, leading junior engineers to higher-paying positions in other companies38. This suggests that close collaboration with colleagues, particularly mentors, has a direct effect on the career advancement of junior employees. In contrast physical distance can constrain access to mentorship opportunities and skill-building, especially for female employees38. In contrast, as the trend towards remote and hybrid work arrangements grows, certain companies, such as X (formerly Twitter) under Elon Musk’s leadership, have mandated a return to office-based work39. This shift has prompted researchers to advocate for the abandonment of traditional, control-oriented managerial strategies in favour of strategies that align with evolving work dynamics and prioritization of employee autonomy and adaptability40.

Impact on well-being

The challenges of maintaining work-life balance in a remote work setting were examined through the survey item “I find it difficult to maintain a healthy work-life balance while working remotely.”36. While remote work is positively correlated with job satisfaction and overall job-related well-being, research indicates that remote workers often struggle to detach from their duties after working hours41. This inability to “disconnect” highlights a crucial issue in maintaining work-life balance for remote employees. Drawing on Social Exchange Theory, Felstead and Henseke41, suggest that remote workers perceive the flexibility offered by remote work as being accompanied by certain trade-offs. Additionally, Border Theory challenges the blurring boundaries between work and home life, as the end of work hours becomes less defined.

Grant, Wallace, and Spurgeon42 further discuss the difficulty employees face in setting boundaries. However, some participants expressed satisfaction with the blurred boundaries, as they could work during off-hours, allowing them to work outside conventional hours and allocate typical work hours in other activities. This highlights the need for adaptive behaviors among remote workers to manage these blurred boundaries effectively42. Buonomo et al.29, using the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory—which supports individuals’ effort to protect existing resources while seeking to acquire additional valuable resources—emphasize the importance of a strong support network among colleagues in maintaining work-life balance. They find that remote workers who view their job as a valuable resource and who receive support from their colleagues experience better work-life balance. This relationship is further enhanced by job satisfaction, which acts as a stabilizing resource for remote employees. Additionally, Buonomo et al.29 underscore the importance of managerial communication with remote employees, addressing emotional well-being, time management, stress, and work-life balance29. Proactive organizational support systems help safeguarding the mental health and overall well-being of remote workers, thereby fostering a healthier and more balanced remote work environment29.

Challenges associated with remote work

The challenges of remote work were assessed through the survey item “I find remote work more challenging than in-office work (e.g., isolation, more distractions, time zone differences).”36. Remote work presents a range of challenges that affect both personal and professional aspects of employees’ lives. While these challenges often lead remote workers to seek opportunities for self and professional growth, they can also foster feelings of isolation, both personally and socially43. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many employees struggled to adapt to the new remote work reality, facing increased distractions and a disrupted sense of routine outside the traditional workplace environment, which further destabilized their work-life balance44. Using the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory and the challenge-hindrance framework, Franken et al.44 explored these experiences. According to COR theory, individuals strive to preserve resources they deem valuable. The challenge-hindrance framework further suggests that employees embrace manageable challenges but, when faced with overwhelming obstacles, may conserve their resources by disengaging from tasks they view as unmanageable (Cavanaugh et al.45, in Franken et al.44). Franken et al.44 concluded that a home environment, if not well-suited as a workspace, can lead to resource loss, particularly when it lacks ergonomic adaptations. Additionally, inadequate technological support can exacerbate this sense of resource depletion, creating a challenging environment for remote workers. Oleniuch46 also highlights differences between experienced and inexperienced remote workers. Inexperienced remote workers are more likely to report a decline in living comfort, while experienced remote workers frequently mention issues of isolation and the need for self-discipline. Overall, the literature suggests that remote work requires a diverse skill set to effectively manage its unique challenges, emphasizing adaptability, resource management, and self-motivation.

Productivity perceptions

We asked following item “I feel less productive while working remotely (more distractions, no focus, bad time management, etc.).”36. Research indicates that remote work can enhance productivity and employee satisfaction when accompanied by appropriate solutions to its challenges.

Recent research highlights the dual nature of remote work in shaping employee motivation and productivity. According to Safri et al.47, remote work arrangements offer several benefits, including reduced commuting time, fewer unnecessary meetings, improved focus in a home environment, and greater autonomy—factors that can enhance employee motivation and overall output. However, their study also identifies key challenges such as technical issues, diminished concentration at home, weakened team cohesion, and communication difficulties. These drawbacks can negatively affect organizational structure and reduce productivity if not properly addressed. The authors further emphasize that inadequate management of psycho-social risks in remote work environments—such as social isolation, work-life imbalance, and lack of managerial support—can lead to increased absenteeism, higher turnover rates, and lower employee well-being, ultimately undermining organizational performance.

Spatial factors, relocation practices and mobility patterns

Division of hours between remote and in-office work

Transitioning from the broader benefits, challenges, and implications of remote work to the specific spatial dynamics of participants’ working arrangements, respondents were asked to quantify their weekly division of hours between remote and in-office work through the item: “On average, what amount of time of your weekly work schedule do you perform remotely/ in the office?”.

Participants selected their preferred location for remote work from three options: (1) the home, (2) a third place (libraries, cafes, community buildings, etc.) and (3) a co-working space. For those preferring third places or co-working spaces, they were asked to indicate by choosing yes or no if their preference was linked to (1) the availability of car parking, (2) the accessibility via public transport and (3) its proximity within walking or cycling distance from home. This section aimed to provide an understanding of participants’ remote work arrangements.

Access to services and amenities

The survey assessed access to services and amenities through the item: “When working remotely, do you currently have access to the following amenities within a 15-minute walk?”48,49. Participants were also asked to indicate the importance of each amenity. This approach enables an evaluation of the accessibility to essential amenities for remote workers, linking remote work preferences to daily routines and lifestyle choices. Proximity to amenities such as schools, groceries, green spaces and healthcare services can influence the attractiveness and feasibility of remote work, shaping work-life balance, productivity, and overall well-being. Research suggests that remote workers increasingly prioritize access to amenities that enhance their quality of life and work-life balance, while the shift towards remote work has led to a revaluation of location attractiveness, with emphasis on green spaces, educational facilities, and social amenities50. These trends underscore the growing importance of localized infrastructure in supporting the evolving needs of workers.

To assess access to services and amenities during remote work, participants evaluated a predefined list comprising of (1) childcare/schools, (2) restaurants/cafes, (3) grocery store/ retail (e.g., laundry, stationery shops, etc.), (4) park/green spaces, (5) healthcare facilities, (6) leisure activities (e.g., cinemas, theatres, shopping), (7) sports facilities and (8) public transport connections. For each item, participants were asked to indicate both availability within a 15-minute walk and its significance by selecting one of four options: (1) yes, and it is important; (2) yes, but it is not important; (3) no, but it would be important and (4) no, but it is not important. This approach provided insights into the accessibility and perceived value of various amenities within walking distance for remote workers.

Changes in workplace and/or place of living

The survey explored relocation behavior through the item: “Have you changed your place of living and/or working due to favorable remote working arrangements since 2020?” and “Name the 5 most important reasons that led to your place of living relocation”.

Decisions to relocate in the context of remote work are influenced by a variety of factors, including personal preferences, family ties, financial capacity, and connections within the community. With the rise of remote work, employees are placing greater emphasis on factors other than workplace proximity, resulting in changes to residential trends. Without the constraints of daily commuting, many individuals choose to relocate to more appealing areas or pursue affordable housing options in suburban or rural regions as well as smaller cities8,19,51. At the same time, the decoupling of living and working locations has created a new market in which localities compete for the physical presence of remote workers52. This trend could potentially bridge the gap between the urban – rural divide fostering a more equitable distribution of population and resources. However, it may also exacerbate urban sprawl, posing challenges for sustainable regional development51. These dynamics highlight the complex interplay between remote work, residential mobility and broader spatial planning considerations. As a result, strategies such as relocation incentives and the creation of coworking spaces have gained prominence, supported by initiatives from both public authorities and private enterprises52,53.

In specific, housing preferences are influenced by several factors including the availability of neighborhood amenities, the quality of local schools, environmental conditions such as pollution and the demands of daily, inflexible commutes. However, in the context of remote working, the absence of a fixed commuting requirement, especially to work, allows individuals greater freedom to live and work from everywhere.

To explore changes in workplace and residence because of remote work, participants were first asked whether they had changed their geographic place of work since 2020. If they responded affirmatively, they were prompted to specify their previous work country and provide the corresponding postal code. Similarly, participants were asked whether they had changed their place of living due to favourable remote working arrangements since 2020. Predefined response options included (1) no, (2) yes, I changed it once, and (3) yes, I changed it regularly. Respondents selecting options 2 or 3 were subsequently asked to specify their previous country of residence and postal code. These questions allowed a comparative analysis of participants’ past and current places of living, hinting at relocation trends linked to remote work.

For respondents who indicated they had relocated since 2020 (options 2 or 3), the final question aimed to identify the key factors influencing their decision to move due to remote work. Participants were presented with a list of 19 potential reasons and were asked to select up to five significant ones in determining their current place of residence. The options included: (1) affordable housing options, (2) living expenses, (3) housing size, (4) change in workplace (different employer, enterprise, etc.), (5) change in employee services, (6) retirement, (7) schooling for children, (8) health reasons, (9) proximity to workplace area / co-working spaces, (10) working conditions environment, (11) proximity to nature, (12) quality of life, (13) safety, (14) digital infrastructure, (15) proximity to family and friends, (16) proximity to urban area, (17) proximity to rural area, (18) cultural immersion, (19) access to like-minded community (remote workers, digital nomads). This question allowed us to capture the different motivations behind relocation.

Commuting patterns

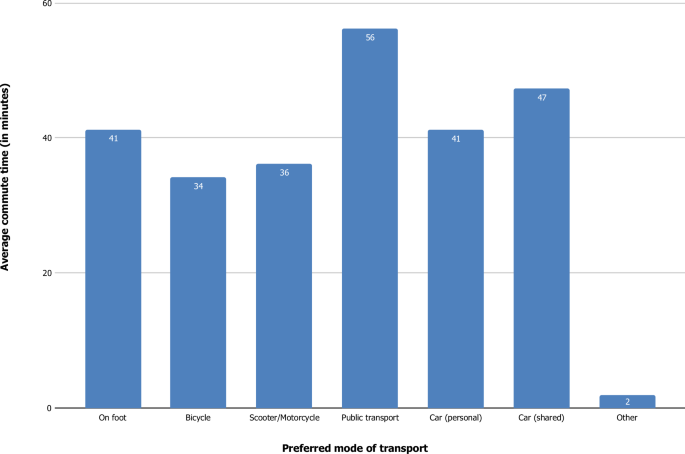

The survey explored commuting behaviour through the item: “How much time do you spend on commuting to work and how do you usually commute to work?”. The impact of remote work on transportation and mobility patterns is a key debate, as the shift towards remote and hybrid work arrangements has redefined traditional commuting demand. Peak travel days and hours are shifting complicating the prediction of travel behaviours and the strategic planning of infrastructure investments. Research indicates that remote work can contribute to the reduction of daily car usage, alleviating traffic congestion, and promoting the use of eco-friendly means of transportation. However, it is also indicated that remote work might lead to longer, but less frequent commutes, altering mobility dynamics54,55. The trend of remote workers to relocate to suburban areas or smaller cities further reshapes transportation needs. Such relocations may increase pressure on existing road infrastructure and create demand for expanded public transportation systems, potential leading to greater reliance on private vehicles8. Additionally, the travel behaviour of remote workers is significantly influenced by the surrounding land uses and allocated amenities, as well as the accessibility of transportation network near their residences55. These findings highlight the complex interplay between remote work, mobility patterns and urban planning, necessitating adaptive approaches to infrastructure and transportation system development.

To assess commuting patterns, we asked participants to report on the average time spent commuting to work, measured in minutes per commute. This provided a foundation for conceptualising the extent of their commuting range. Participants were then asked to indicate all applicable modes of transport they used from a predefined list: (1) on foot, (2) bicycle, (3) scooter/motorcycle, (4) public transport (bus, metro, tram, ferry, train), (5) personal car, (6) shared car, or (7) not applicable for those that do not commute for work (“other” category). These questions were designed to capture the diversity of commuting behaviours in relation to the ways remote work might influence or be influenced by commuting patterns.

Demographics and employment context

The last section of the survey focuses on collecting demographic information to contextualize participants’ responses within a broader socioeconomic context and professional framework. Participants were asked to provide details on their gender, age, years of education and professional experience. Furthermore, the survey collected information on participant’s current place of residence and work, including geographical location (municipality), as well as the industry sector in which they are employed, categorized to the NACE industry classification. NACE (Nomenclature des Activités Économiques) is the European statistical classification of economic activities. It is a hierarchical system used to categorize and analyze economic activities across the European Union and beyond. NACE provides a framework for collecting and presenting statistical data related to economic activities in various domains like production, employment, and national accounts56. Employment status is also assessed, with subcategories ranging from paid employment and self-employment to voluntary work. This section concludes with an open-ended question, allowing participants to share any additional comments. These demographic insights ensure that the survey captures a diverse range of perspectives and enables the identification of patterns and trends across different demographics, professional groups and geographical context.

The European Union began to acknowledge economic, social and territorial cohesion as the foundational pillars of its overarching vision and developmental agenda. However, it was not until the mid-1980s that more concerted and formalized efforts were undertaken to advance these goals. In furtherance of these goals, the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund Plus and the Cohesion Fund function as pivotal instruments, each target specific dimensions such as – innovation, environmental sustainability, transport, social inclusion- while converging upon the overarching goal of strengthening the EU’s territorial cohesion.

Exclusion criteria

We do not exclude outliers. Participants are excluded if they meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) Failure to give informed consent. (2) Taking the survey more than once, as indicated by Prolific ID; only the first test will be analyzed. (3) Failure to finish the survey.