Potential for early detection: The findings could help scientists identify at-risk youth sooner, paving the way for earlier, more personalized mental health interventions.

When you’re a teenager, it’s easy to feel like the world is watching your every mistake. For some kids, that sense of self-consciousness fades as they grow up. For others, it deepens into full-blown anxiety.

A new study led by researchers at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences may help explain why — and could eventually make it easier to spot teens most at risk before anxiety takes hold.

The research, published in JAMA Network Open, found that combining two kinds of brain scans can better predict which teens are likely to experience greater anxiety as they get older. The work sheds new light on how the adolescent brain responds to mistakes and why those responses vary from person to person.

The teens were part of a rare, decades-long study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, which has followed participants from infancy through adolescence to explore how early temperament influences brain development and mental health. Many had been identified early in life as having what psychologists call a “fearful temperament” — a tendency to react shyly or cautiously to new people and situations. While this temperament is known to raise the risk of anxiety later in life, not all kids with it develop anxiety.

“We wanted to know why some kids develop anxiety while others don’t, even when they share similar early life traits,” said Emilio Valadez, assistant professor of psychology at USC Dornsife and the study’s lead author. “By looking at how the brain processes mistakes, we hoped to find clues about who’s more likely to struggle with anxiety as they grow.”

Scanning teen brains to forecast anxiety risk

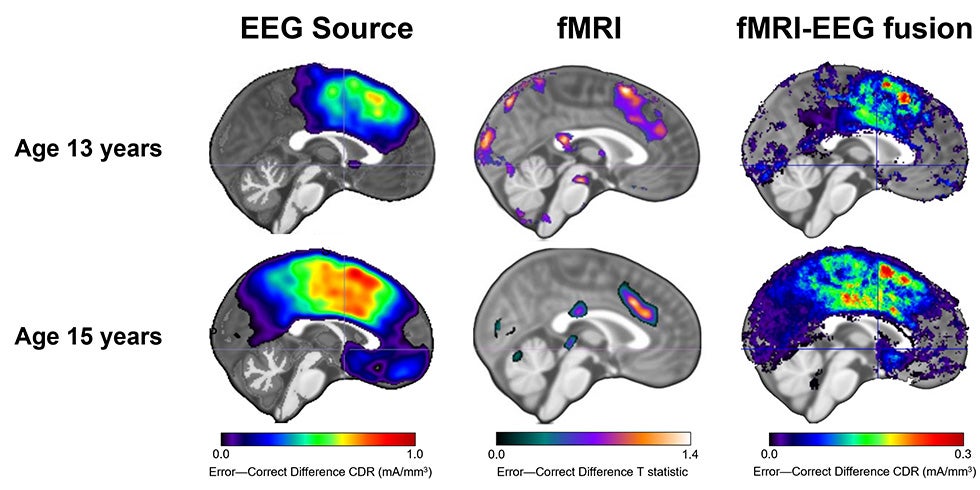

To find those clues, the researchers asked the teens to complete a simple computer test designed to provoke small mistakes — pressing the wrong button in response to a quick series of arrows. While they worked, the teens’ brain activity was measured using two technologies: electroencephalography (EEG), which tracks brain activity over time, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which shows where that activity happens in the brain.

Each method captures part of the picture. EEG is lightning-fast but fuzzy on location, while fMRI is slow but pinpoint precise.

The team scanned the teens twice, once at age 13 and again at 15, and developed a novel technique to fuse the data from the two imaging methods. This “EEG-fMRI fusion” gave a much clearer view of how the brain responds to mistakes and how those patterns change over time.

It’s like using both your eyes together to get depth perception,” Valadez explained. “Suddenly, the brain’s activity comes into much clearer focus.”

Scientists scanned the brains of teens at age 13 and again at 15 using EEG and fMRI, then combined EEG and fMRI scans to produce a more meaningful picture of brain activity at each age. (Image: Courtesy of Emilio Valadez.)

Scientists scanned the brains of teens at age 13 and again at 15 using EEG and fMRI, then combined EEG and fMRI scans to produce a more meaningful picture of brain activity at each age. (Image: Courtesy of Emilio Valadez.)

Combined teen brain data that’s greater than the sum of its parts

When the researchers analyzed the data, they discovered that EEG or fMRI alone didn’t do much to predict changes in anxiety. But when they combined the two, the results were striking.

The fused data explained about 25% of the differences in how teens’ anxiety levels changed between ages 13 and 15, allowing much stronger predictions than could be made solely from their early temperament, age, gender and initial anxiety levels.

“This was honestly a surprise,” Valadez said. “We expected maybe five or 10%. But 25% is a big leap. I actually thought I had made an error at first.”

The study also found that a teen’s early temperament changed how certain brain areas were linked to later anxiety. For teens who were very shy or cautious as babies, more activity in one region — the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, which helps the brain detect mistakes and potential threats — predicted greater anxiety later on. But another region, the posterior cingulate cortex, seemed to have a protective effect: Teens with fearful temperaments who showed more growth in this region’s activity over time tended to be less likely to become anxious.

In simpler terms, how the brain responds to mistakes — and how that response evolves during a key window in adolescence — appears to shape whether anxiety gets better or worse.

Dual imaging could mean earlier help for anxious teens

The findings suggest that scientists may one day use brain imaging to better identify which teens are most at risk for anxiety disorders before symptoms fully appear. That could open the door to earlier, more personalized treatments.

“This study doesn’t have immediate day-to-day implications for families,” Valadez said. “But it’s a step toward being able to predict anxiety risk earlier, which could eventually help us prevent mental health problems before they start.”

The research also underscores the value of combining different brain imaging tools.

“No single tool can tell the whole story,” Valadez said. “When we integrate data across methods, we can get a more complete understanding of how the brain supports mental health.”

Looking ahead, Valadez and his team plan to explore whether similar predictions can be made even earlier in development — perhaps when children are as young as 8 or 9 years old — and whether other brain functions, like memory or attention, might help explain anxiety risk.

“The ultimate goal,” Valadez said, “is to read the brain’s story early enough to know which kids might need extra support, and to give them that support before anxiety becomes a lifelong struggle.”

About the study

In addition to Valadez, study authors include Santiago Morales of USC Dornsife; Yi Feng of UCLA; Stefania Conte of Binghamton University; John Richards of the University of South Carolina; Lucrezia Liuzzi and Daniel Pine of the National Institute of Mental Health; Marco McSweeney and Nathan Fox of the University of Maryland, College Park; Enda Tan of the University of British Columbia; George Buzzell of Florida International University and the Center for Children and Families; Anderson Winkler of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley; Elise Cardinale of The Catholic University of America; and Lauren White of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Penn Medicine.

Funding was provided by National Institute of Mental Health grants K23MH130751 and U01MH093349, and National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program grant ZIAMH002782.