During the past few weeks, I’ve seen a proliferation of A.I.-generated video in my social-media feeds and group texts. The more impressive—or, at least, more personalized—of these have been the work of Sora 2, the updated version of OpenAI’s video-generation platform, which the company released on an invitation-only basis at the end of September. This iteration of Sora comes with a socially networked app, and it appears to be much better at integrating you and your friends, say, into a stock scene. What this means is that, when you open up Sora 2, you’ll likely see a video of someone you know winning a Nobel Prize, getting drafted into the N.B.A., or flying a bomber plane in the Second World War.

When I first started seeing these videos, my internal monologue went something like this: Whoa, that really looks like me/my friend. Ha, that’s cool. This is going to be a problem for society.

This set of thoughts, usually in this order, has been part of the A.I. industry’s pitch to consumers—and it’s worth pausing in this moment and asking if those reactions still hold the same sway as they did when ChatGPT was launched to justifiably breathless reviews and speculation about the future three years ago. Sora 2 has been met with relatively little fanfare, at least in comparison to earlier releases from OpenAI. I was impressed by the videos I’ve seen, but I find myself feeling similarly meh. I opened the app, saw a video of my friend Max giving a TED Talk, chuckled, and then went back to watching YouTube. I haven’t opened it up since.

I think of myself as a cautious A.I. believer—if I were a Christian, I would be the type who goes to church two Sundays a month, knows the hymns, but mostly keeps up his faith as a matter of social norms and the possibility that God actually is angry. I don’t believe artificial general intelligence, A.G.I., will gut the world, but I do think a lot of us will be working in new jobs in the next decade or so. (These changes, I suspect, will mostly be for the worse.) I also have spent a good deal of time working on documentaries, which has driven home for me how much time and money typically goes into producing even a good minute of traditional film. So, what’s changed? Why do these updates feel increasingly like the unremarkable ones that periodically hit my iPhone?

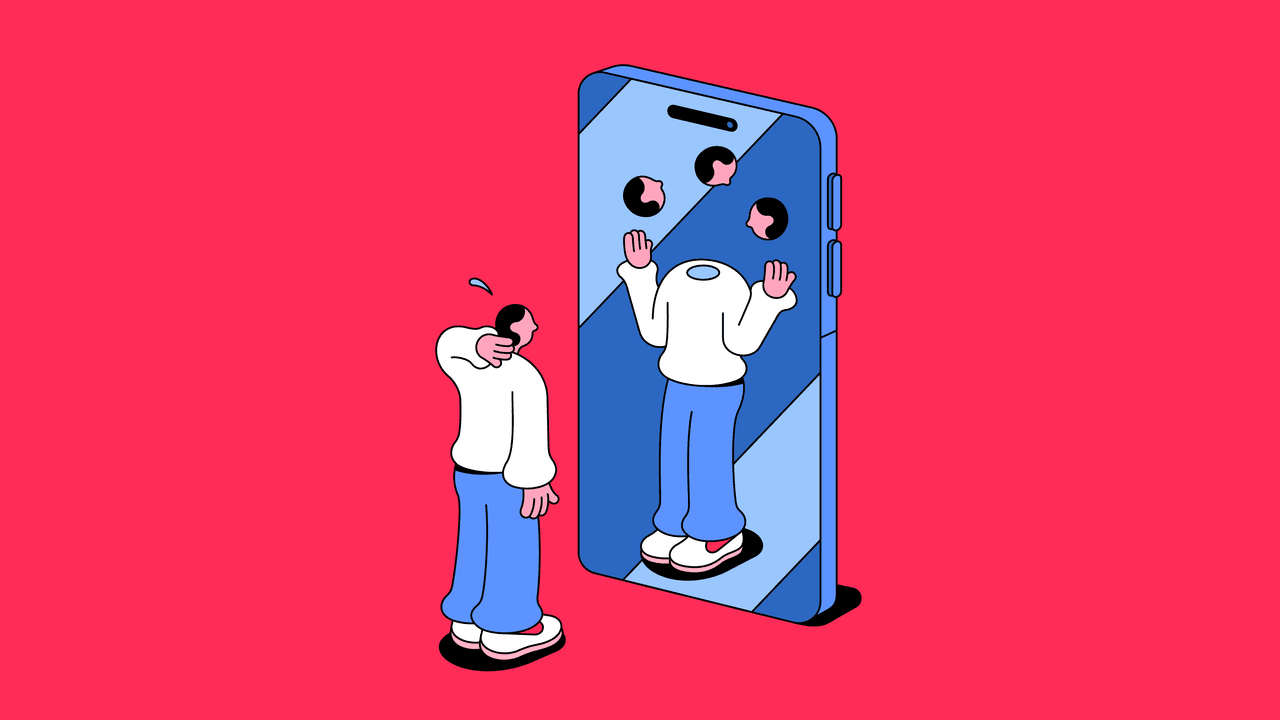

The most powerful trick that A.I. pulls is to put you, or at least your digitized self, into some new dimension. It does this by, for instance, converting your family photos into Studio Ghibli animations, or writing in your voice, and, now, by grafting your face onto your favorite movie scenes. All of this tickles the vanities of the user—even if he’s the President of the United States, apparently—and creates an accessible and ultimately personal connection to the program. You might not be impressed by watching Claude, the large language model created by the A.I. startup Anthropic, write code for six straight hours because, chances are, you can’t follow what it’s doing, nor, unless you’re a coder, do you likely care too much about the possible ramifications. But, when you see yourself riding a dragon as if you’re in a copyright-gray-zoned version of “Game of Thrones,” you will probably take notice.

For the most part, we enjoy A.I. because it lets us gaze into a better mirror, at least for a little while. And by giving well-timed teases of what the A.I. future might look like, the companies behind these programs nudge us to ask if the A.I. version of our lives might not be better than the real ones. It’s worth noting that this is more or less how strip clubs work. The customers are sold a fantasy, and they keep throwing money around because they hold out hope, however dim, that the teases will turn into something else. Under the spell of such intense flattery, we all become easy marks.

The A.I. boom of the past few years has been built in the space between the second thought I had when I first saw Sora 2 videos and the third—between “Ha, that’s cool” and “This is going to be a problem for society.” Many of us have that third thought, but few of us, save for the A.I. doomers proselytizing about the existential threats posed by this technology, have sat with it long. We wonder if these cute, obsequious chatbots will someday try to kill us because that’s what happens in “The Terminator” and “Ex Machina” and “2001: A Space Odyssey.” We don’t actually have a working theory of how Claude or Grok will subjugate the human race, nor, I imagine, do we really believe that will happen.

Why, once our brains are finished being mildly impressed with the latest step in A.I. technology, do we immediately start sketching out doom scenarios? The people making threats often happen to be financially incentivized to make A.I. seem as world changing and dangerous as possible. There are true believers among the doomers, but I suspect that a good portion of people who work at A.I. companies have no strong opinions about the threats of A.G.I. Some of them, given how engineering talent follows capital in Silicon Valley, may have worked previously at a cryptocurrency startup. And if they spent any amount of time in crypto, especially during the early days of apocalyptic Bitcoin philosophizing, they may recognize the similarities in the rhetoric of Bitcoin maximalists—who preached about the inevitability of deflationary currency, the coming upheaval of the world markets, and the need to use this power for good—and the A.I. Cassandras, who say that SkyNet is coming for us all. When the iPhone never changes and Bitcoin just becomes an investment vehicle, the only way left to grab people’s attention is to tell them they might all die.