Illustration by ZME Science/Midjourney.

Illustration by ZME Science/Midjourney.

In the heart of the Yucatán more than a thousand years ago, a group of Maya astronomers, known as daykeepers, tracked the movements of the Moon with such precision that they could foresee solar eclipses centuries in advance. Now, researchers John Justeson and Justin Lowry have finally decoded their methods for building eclipse tables in a new study.

“The earliest version of the eclipse table seems to have been a repurposed revision of a less complex table,” the authors write, “which listed 405 successive lunar months, each lasting either 29 or 30 days.” From that humble start, the Maya built a framework capable of predicting every solar eclipse visible in their territory between 350 and 1150 CE.

The Maya Math Behind Predicting Eclipses

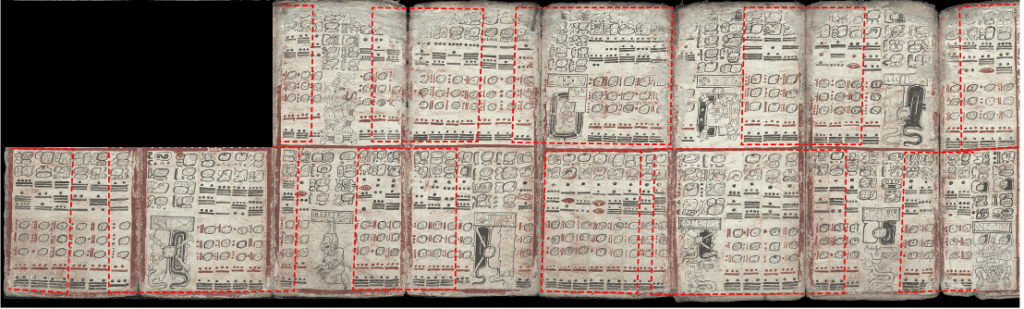

To modern eyes, the eight-page eclipse table of the Dresden Codex looks like a dense grid of hieroglyphs and numbers. To Mayanists, however, these tables hide a rhythm of cosmic regularity. The table covers 405 lunar months (just over 32 years) and contains 69 new moons, of which 55 mark possible solar eclipses.

Each entry, or station, represents a new Moon when an eclipse could occur. Most are spaced six lunar months apart, roughly 177 days, because that’s how long it takes for the Moon to return to the same alignment relative to Earth and the Sun.

Earlier scholars assumed each new table began after the previous one ended. But this, Justeson and Lowry show, would quickly throw off predictions. The Maya, they argue, used two precise reset points: 223 and 358 lunar months. These correspond to the known saros and inex cycles of eclipses.

The saros cycle is an eclipse cycle of approximately 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours, after which the Sun, Earth, and Moon return to nearly the same relative geometry. The inex cycle is a slightly shorter period of about 10,571 days (or 29 years) that also aligns eclipse patterns.

As the authors explain, “Restarting an eclipse table at these intervals, and at these ratios, would have enabled daykeepers to reset the table reliably for a few millennia.”

The researchers’ reconstruction shows that by mixing four resets at 358 months (the inex cycle) for every one at 223, the Maya could have maintained accuracy across generations, a mathematical calibration as elegant as anything found in Babylon or Greece.

A Civilization That Counted the Sky

Six sheets of the Dresden Codex (pp. 55-59, 74) depicting eclipses, multiplication tables and the flood. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Six sheets of the Dresden Codex (pp. 55-59, 74) depicting eclipses, multiplication tables and the flood. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Maya astronomy was part science, part divination. The daykeepers worked with two intertwined calendars: a 260-day ritual cycle used for astrology and prophecy, and a 365-day civil calendar that tracked the solar year. Around 500 BCE, they began linking the lunar cycle to the 260-day divinatory count.

By the Classic period, between 350 and 900 CE, the Maya had compiled enough eclipse observations to discern long-term patterns. The Dresden Codex — copied around the 12th century from older sources — preserves the culmination of that knowledge.

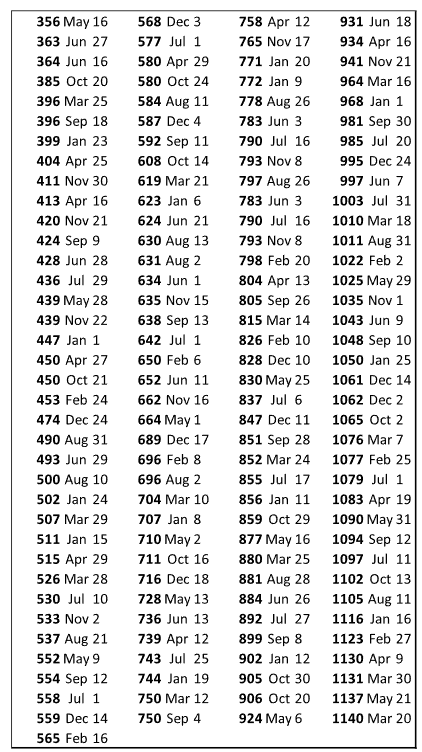

Dates of solar eclipses judged observable in the Mayan territory, 350 to 1148 C.E. Credit: Science Advances, 2025.

Dates of solar eclipses judged observable in the Mayan territory, 350 to 1148 C.E. Credit: Science Advances, 2025.

In their analysis, Justeson and Lowry cataloged 145 solar eclipses visible across the Maya world over eight centuries. They found that eclipses separated by 669 lunar months, roughly 54 years, tended to recur near the same longitude and time of day. The Maya could therefore recognize these cycles and fold them into their predictions.

The dashed boxes surround the sequences of six or (once) seven stations categorized as “intended” in Fig. 1; stations between successive dashed boxes are contrived stations. The first two stations, at the upper left, lack a vertical dashed line to the left because four intended stations would precede the table’s first eclipse station; the last four stations, at the lower right, lack a vertical dashed line to the right because two intended stations would follow them. Dashed lines form rectangles surrounding each series of consecutive intended stations; a picture, above noncalendrical glyphic passages that contain no numerals, usually occurs between successive rectangles and otherwise immediately before the last calendrical column in a rectangle. Credit: Science Advances, 2025.

The dashed boxes surround the sequences of six or (once) seven stations categorized as “intended” in Fig. 1; stations between successive dashed boxes are contrived stations. The first two stations, at the upper left, lack a vertical dashed line to the left because four intended stations would precede the table’s first eclipse station; the last four stations, at the lower right, lack a vertical dashed line to the right because two intended stations would follow them. Dashed lines form rectangles surrounding each series of consecutive intended stations; a picture, above noncalendrical glyphic passages that contain no numerals, usually occurs between successive rectangles and otherwise immediately before the last calendrical column in a rectangle. Credit: Science Advances, 2025.

“After three spans of 405 months, with 190 intereclipse intervals among 20 eclipses, a fairly uniform pattern would emerge,” the researchers write. In other words: watch the sky for a few generations, and the universe starts to talk back in numbers.

Accuracy Over Centuries

For the Maya, eclipses were very important, seen as cosmic warnings. Darkness devouring the Sun might signal divine anger or renewal. Yet beneath the myth, their predictions rested on data carefully recorded over centuries.

When the researchers reconstructed the table’s historical range, they found it likely corresponded to the years 1083–1116 CE. Remarkably, that same method for the eclipse table could still predict modern eclipses over Mexico (as long as someone made new tables using the same reset procedures). Without those periodic resets, the table would gradually drift out of alignment due to the slight mismatch between lunar months and the eclipse cycle.

“The table would have anticipated every solar eclipse observable in the Mayan territory from a century or two after the first evidence of the Mayan lunar calendar to at least the era of the extant eclipse table, 700 years later,” the authors conclude.

Seven centuries of reliable predictions, built without telescopes, without calculus, without even a concept of gravity. It’s fascinating what you can achieve with just careful watching, meticulous record-keeping, and the mathematical insight to turn observation into prophecy.

We now live in an age when we can calculate eclipses thousands of years into the future with computer precision. But it’s humbling to recognize that a thousand years ago, Maya astronomers were doing much the same thing. And they were armed only with their eyes, their calendars, and an unshakeable conviction that the universe spoke in numbers.

The new findings were published in Science Advances.