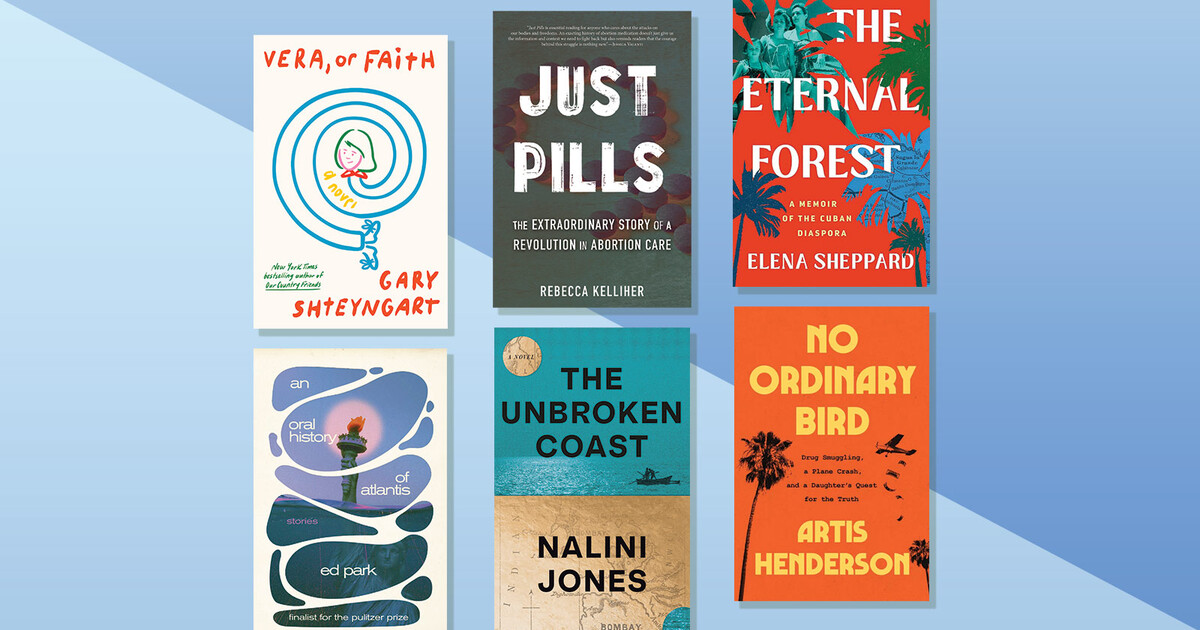

Vera, or Faith

By Gary Shteyngart

Judging by the chapter titles of Columbia writing professor Gary Shteyngart’s latest novel, the book’s ten-year-old protagonist, Vera, has weighty responsibilities on her mind: “She had to survive recess,” “She had to hatch a plan,” and of course “She had to hold the family together,” to name just a few. That family consists of her Russian-immigrant dad, her WASP stepmom (whom she calls “Anne mom,” in contrast to her estranged Korean birth mom, known as “mom mom”), and her younger brother. Set in a dystopian near-future full of self-driving cars, authoritative AI bots, and a troubling political climate, Shteyngart’s latest is a smart satire with charm to spare.

Just Pills

By Rebecca Kelliher ’13BC, ’21JRN

The development of the abortion pills mifepristone and misoprostol in the 1970s and 1980s was in many ways a medical miracle, providing millions of women often lifesaving ways to end pregnancies. In her first book, science journalist Rebecca Kelliher delves into their invention, the battle for their legalization, and their adoption around the world, talking to more than two hundred people who have used, administered, and advocated for the pills. In a post-Dobbs America, the fight for abortion rights has become increasingly urgent, and Kelliher’s project is ambitious and timely.

The Eternal Forest

By Elena Sheppard ’20SOA

Before Fidel Castro seized power in 1959, Elena Sheppard’s grandparents, Gustavo and Rosita, were raising their two girls in idyllic Cifuentes, Cuba. But when Gustavo was placed on a list of political undesirables, the family left for the US, taking only one suitcase and five American dollars. Elena arrived nearly three decades later; she was the first American-born in her clan, but she was raised on her family’s memories of “that crocodile-shaped island fueled by God and music and sugar money and rum.” She tells those stories warmly and elegantly here, weaving together family lore and Cuban history to create a vibrant portrait of exile and repatriation.

An Oral History of Atlantis

By Ed Park ’95SOA

Technology is seeping into every corner of our lives, and the AI revolution threatens to upend the way our world works. So how, in this robot-run society, do we retain our humanity? That question is central to Pulitzer Prize finalist Ed Park’s latest work of fiction — a quirky, Barthelme-esque story collection. In one piece, a man contemplates his life via a series of password-recall prompts. In another, a hacker figures out how to make an e-reader splice the texts of books together, creating a disorienting (but maybe revolutionary?) new way to read. Together, the stories are an amusing look at our new normal.

The Unbroken Coast

By Nalini Jones ’01SOA

In a small Catholic enclave of Mumbai, Francis Almeida, a retired history professor teetering on the brink of dementia, runs his bike into Celia D’Mello, a feisty eight-year-old from the nearby fishing village. Missing their globe-scattered grown children, Almeida and his wife take Celia under their wing, and two families’ lives become intertwined in unexpected ways. Nalini Jones’s debut novel, which follows the Almeidas and D’Mellos through three decades and countless tragedies, is a lovely and often heartbreaking portrait of a community barreling into modernity.

No Ordinary Bird

By Artis Henderson ’10JRN

When Artis Henderson was five years old, she boarded a small plane piloted by her father, Lamar Chester. Moments later, it crashed, leaving Artis injured and her father dead. For the rest of her childhood, it was referred to as “the accident.” But decades later, she learned that it hadn’t been an accident at all, and that her beloved father wasn’t who she thought he was. Oddly, this is Henderson’s second memoir about a devastating crash — her first book, Unremarried Widow, chronicled life after her husband was killed in a helicopter accident in Iraq. There’s more drama to her new book, a stranger-than-fiction story packed with sabotage, betrayal, and international intrigue. But at the heart, both books are about gut-wrenching grief, which Henderson writes about with remarkable grace.