Opinion: It’s not every day you tell a positive story about climate. But 10 years after the Paris Agreement, the data tells one. When nearly 200 nations struck the landmark deal in December 2015, analysts and commentators were cautious, some outright sceptical. That year’s forecasts from BP and the International Energy Agency assumed only modest growth in renewables. Electric vehicles were niche and expensive. Fossil fuels were expected to dominate for decades.

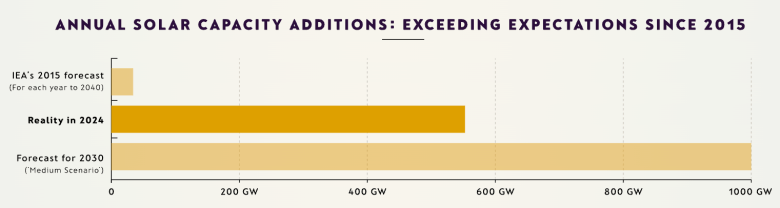

Ten years on, the clean energy transition has unfolded faster than anyone dared predict. Global non-fossil generation, which BP thought would hit 38 percent by 2035, reached 41 percent in 2024. Solar power, dismissed as uneconomic by The Economist in 2014, became “the cheapest electricity in history”. In 2024, the world installed 553 gigawatts of solar capacity, 15 times more than the International Energy Agency predicted a decade ago.

Wind kept pace too, and together they now generate more power than coal. Renewables are even beginning to outpace electricity demand growth. Early German and UK subsidies for solar and offshore wind – once written off as economic folly – proved to be global gifts.

Policy architecture has gone global. Climate Framework Laws have tripled since 2015, many embedding carbon budgets and independent advice for long-term decarbonisation. National climate policy tools are up sevenfold since 2015. Despite Trump’s rollbacks, net zero targets still cover 83 percent of the global economy, most enshrined in law or policy; 19 of the G20 still target net zero by mid-century.

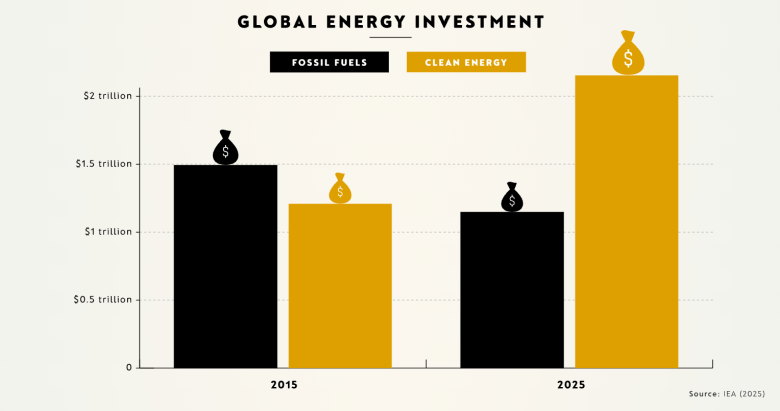

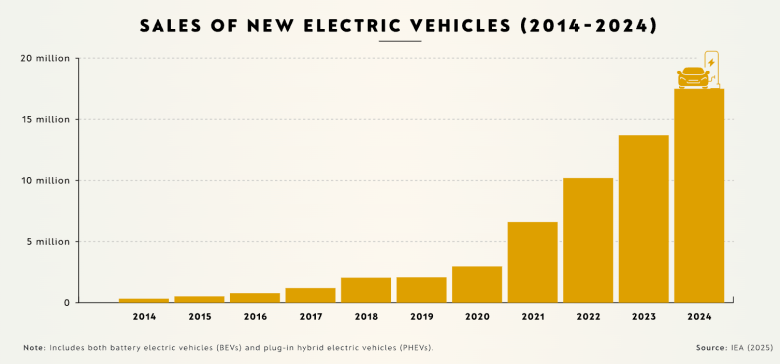

Clean energy investment is now double that of fossil fuels, led by the US, EU, China and India. EVs have surged to 20 percent of global new car sales and are on track to reach 40 percent by 2030, a decade ahead of 2015 projections. In 2015, the world hoped for 100 million EVs by 2030. We’re now on course to reach that milestone in 2027. In China and the UK, the clean energy economy is growing three times faster than the broader economy. Jobs in clean energy – over 36 million globally – outnumber those in oil, gas, coal and fossil-engine manufacturing combined. The gap’s widening.

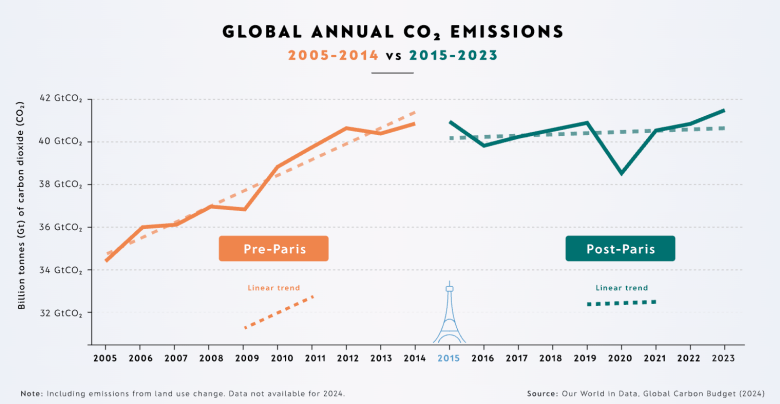

Most importantly, global CO2 emissions have plateaued. Between 2005 and 2014, they rose by over 18 percent. Since Paris, they’ve edged up by about 2 percent. Annual green house gas emissions growth has slowed fivefold – from 1.7 percent a year in the decade before Paris to 0.3 percent after. We’re at, or near, peak emissions.

Of course, to meet the Paris temperature goals and achieve net zero by mid-century, global emissions must decline, not simply flatten. The speed and depth of that shift will depend on the strength and consistency of policy action — and what happens in China. We can be cautiously optimistic: clean energy growth has already helped the world’s largest emitter’s CO2 emissions fall by 1 percent year-on-year in the first half of 2025, extending a trend that began in March 2024.

The Paris Agreement’s greatest achievement was to send an incontrovertible signal that the world intended to stop climate change. Policymakers, markets and entrepreneurs mobilised, creating feedback loops of ambition and innovation still compounding today. When global emissions finally enter structural decline, it will mark the end of the beginning of global climate action. But as environmentalist Bill McKibben warns us, “winning slowly is the same as losing”. Even if stated policies are fully delivered, 2.6C of heating is on the cards this century, far beyond the bounds of climate safety.

The next test comes at COP30 in Brazil where countries are expected to submit upgraded carbon-cutting plans to 2035. The Brazilian presidency’s ‘Global Mutirão’ aims to align energy, nature and livelihoods – a collective effort to close the finance gap, protect forests and accelerate the shift to renewables. If the past decade proved the transition could happen faster than imagined, the next can beget more progress, not just in gigawatts and gigatonnes, but in finance, fairness and resilience.

The global energy transition is unstoppable, but it is slowdownable. Populism, protectionism and fiscal tightening have slowed progress. With the US stepping back twice under Trump, China is sweeping into the leadership vacuum – financing renewables across the Global South and exporting clean tech, slashing emissions along the way. Developing nations did least to cause climate change yet face the biggest barriers to finance and technology. Closing that gap, investing in grids and rebuilding trust in multilateralism are the challenges of the next decade. Renewables growth has to beat demand growth year after year, and we need to electrify everything, taking electricity from a fifth of global energy to about two-thirds.

In New Zealand, the same rule applies: where policy and economics are in step, progress accelerates; when politics and short-termism take over, it stalls. We spend about $20 billion a year on fossil fuels, mostly imported. Electrifying households with solar, batteries, heat pumps and EVs could save $10 billion per year by 2040 – with tenfold cumulative savings – while improving our balance of payments and trade deficit. Swapping imported fuels for homegrown electricity is an economic no-brainer that also strengthens energy security and cuts emissions.

Yet we’ve repealed the Clean Car Discount without a replacement, reopened fossil exploration and embraced a liquefied natural gas terminal, ignoring economics and expert advice. Globally, EVs are going bananas, renewables firmed with batteries are beating fossil fuels on price and deployment times, and liquefied natural gas only looks competitive if you’ve already sunk hundreds of millions into a terminal.

The Luxon government has largely ignored proposed electricity-market reform, rejecting eight of 10 recommendations from its own review. It promises to keep the lights on but has missed the bigger opportunity to bring bills down, electrify industry and back households. These moves sit awkwardly with the economics of the transition and will only prolong its culture wars.

The lesson of the last 10 years is simple: strong policy signals and cooperation matters; naysayers don’t. The Paris Agreement showed what happens when intent combines with S-curves. The next decade will determine whether this momentum delivers the first sustained decline in global emissions, the start of the next chapter of climate action.

See the full Ten years post-Paris: A decade that defied predictions infographic and report.