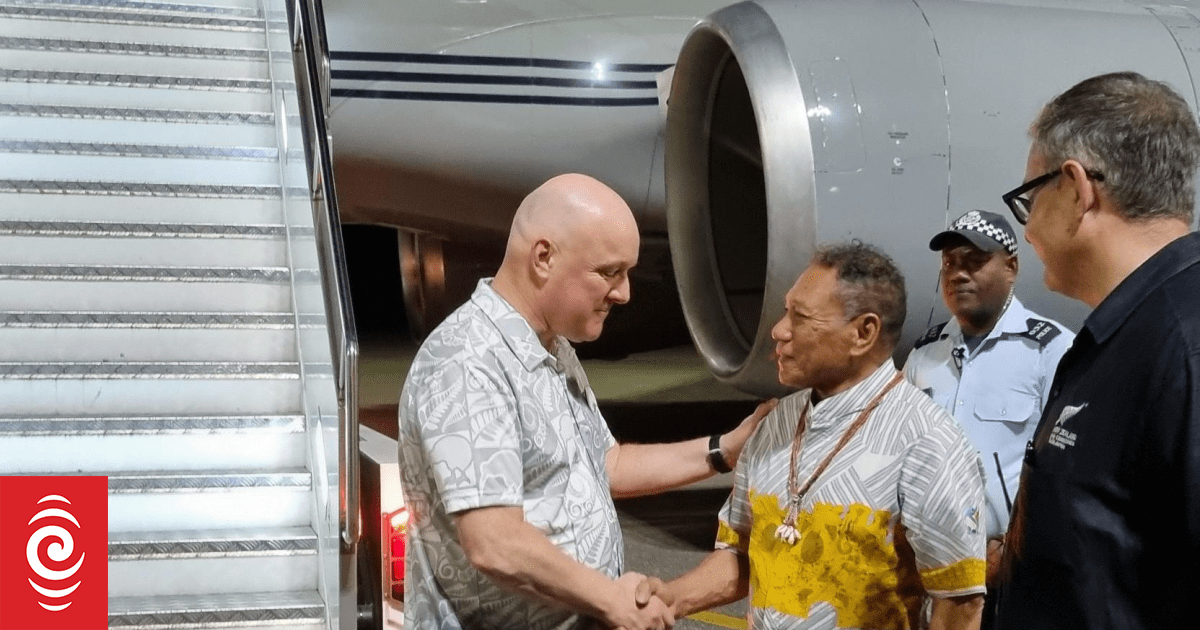

Christopher Luxon arrives in Honiara, greeted by Solomon Islands Foreign Affairs Minister Shanel Agovaka.

Photo: RNZ / Giles Dexter

The Prime Minister goes into this year’s Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Meeting talking up Pacific unity, while disagreeing with a major aspect of this year’s summit.

This year’s meeting in Honiara is a quieter affair, at least numbers wise, with 21 ‘dialogue partners’ excluded from the event.

The partners are non-Forum nations or entities who engage with the region through the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), such as the United States, China, Taiwan, France, and the European Union.

Many of them provide funding for Pacific initiatives, though the region, as any bilateral readout will tell you, is becoming increasingly contested.

The call to bar the partners was made by the hosts, with the Solomon Islands deciding it was better to debate the future of PIF’s regional architecture without those external partners in the room.

It has repeatedly denied it was pressured by China to exclude Taiwan.

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Jeremiah Manele in Honiara for the 54th Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Meeting from 8-12 September 2025.

Photo: RNZ Pacific / Caleb Fotheringham

PIF leaders would deliberate this year on a way forward for dialogue partners, through a Regional Architecture Review.

Anna Powles, an associate processor at Massey University’s Centre for Defence and Security Studies, said the presence of so many partners was sometimes distracting, and with so many important issues on the table this year it may be useful that they were not there.

“In many respects, the decision to limit the summit to only Forum members is a useful way of actually prioritising Pacific priorities and the Pacific Islands Forum agenda, without the distraction of the sort of diplomatic circus which takes place,” she said.

There remained a question as to whether some partners would find a way of attending anyway.

Throughout the build-up, Luxon had stressed there was still a strong sense of unity, while also making New Zealand’s position clear that the dialogue partners should be there.

“The dialogue partners being there is actually a good opportunity to engage with them on particular on development opportunities across the Pacific,” Luxon said.

“Having said all of that, there is very good unity within the Pacific Islands Forum. And so it’s a chance for us to think a little bit more about how the organisation matures, and also how it actually can engage those dialogue partners in a constructive way, because there’s been a lot of them that’s come into the Pacific Islands in recent years.”

Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters had been more bellicose, accusing “outsiders” of influencing the decision, and going as far as to suggest if members had known about the ban they would have opted to hold the meeting in another country.

Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters.

Photo: RNZ / Samuel Rillstone

Powles said while it was within New Zealand’s rights to say it did not agree with a decision, it was not a time for “foghorn” diplomacy.

“It’s a time for more quiet diplomacy, particularly when there are considerable concerns about fragmentation and disunity within the Pacific Islands family and within Pacific regionalism overall. This is a time for quiet, sustained, trusted diplomacy, rather than loud statements, which can potentially be disruptive.”

Much has been made of respecting the ‘centrality’ of PIF, while also recognising each member was its own nation with its own rules, goals, and outlooks.

For example, much of the Pacific wholeheartedly supported Israel, at a time where Australia was recognising Palestine and New Zealand was considering whether to do the same.

New Zealand had reinstated oil and gas exploration, as other PIF members grappled with rising sea levels. The government previously demurred on whether it would contribute towards a Pacific Reslience Facility, before [https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/on-the-inside/526710/is-new-zealand-pulling-its-weight-on-climate-change-in-the-pacific

https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/572436/pacific-resilience-facility-treaty-set-for-signing-in-honiarac omitting $20 million towards it].

New Zealand was spending up large with its Defence Capability Plan, just as the Forum was set to consider a peace declaration.

First proposed by Fijian prime minister Sitiveni Rabuka, the Ocean of Peace declaration was a commitment to principles that embedded peace as the cornerstone of individual and collective policies.

This year’s summit is being held in the Solomon Islands.

Photo: RNZ Pacific / Caleb Fotheringham

AUT Pacific historian Marco de Jong said with this year marking 80 years since the end of World War II, and 40 years since the signing of the Treaty of Rarotonga, it was a “weighty” time to talk about peace.

The declaration was originally seen as an opportunity to push back against geostrategic competition, but de Jong said there were now conflicting designs on what an Ocean of Peace would look like.

He said for it to be meaningful, it must be aspirational and build on what had already come before.

“There’s no use in saying we declare the Blue Pacific to be an Ocean of Peace, and then just simply re-affirming the existing framework,” he said.

“People will be looking out for new language on maybe regulating the use of force, or language around demilitarisation, or climate security that goes beyond the Boe Declaration.”

That declaration, endorsed in 2018, re-affirmed climate change as the single greatest security threat in the Pacific, but also expanded the concept of security to include human security, humanitarian assistance, environmental security and regional co-operation.

De Jong said New Zealand had played a “leading” role in drafting the Ocean of Peace declaration, which may mean New Zealand was facilitating specific priorities at the declaration’s heart.

He said the fact it was a declaration, and not a treaty, reflected in part the contradictary purposes and divided state of regionalism at the moment.

“You have a situation where the geostrategic imperative appears to be to align the region with broader geostrategic objectives, in this case, with the US against China. And you see that with this whole lattice-work of regional security framing,” he said.

“So you see with Australia all of these bilateral deals, say with Nauru, or Tuvalu, or PNG, which all have these strategic trust clauses or security vetoes in them. And so the temptation will be for New Zealand to meddle, to make the Ocean of Peace reflect that broader regional security architecture, things like the Pacific Policing Initiative or the Pacific Response Group of the South Pacific defense ministers meeting.

“But as the US becomes more unreliable, there’s something to be said for the alternative way that Pacific nations see regional security. A focus on climate action, on equitable, human-centered development, on nuclear disarmament. That, to my mind, serves to insulate the region from the worst excesses of geostrategic competition.”

Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown.

Photo: RNZ / Nate McKinnon

The meeting would also be the first time Christopher Luxon was in the same room as Mark Brown since New Zealand paused $18.2m in development assistance to the Cook Islands, over a lack of consultation over a partnership agreement with China.

Neither leader would want their tensions to be a distraction from what the Forum was seeking to achieve this week.

Luxon was sure he and Brown would catch up, and promised civility.

“We’ll have a good engagement. Our officials are working through the risk areas that we see in those documents. That’s ongoing work, but I’m sure we’ll have a very civil and constructive engagement.”

New Zealand is also bidding to host the 2027 PIF, having last hosted in 2011.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.