Quick Take

UC Santa Cruz students report the worst mental health in the UC system, citing stress, anxiety and housing insecurity. The campus has a bucolic scenic setting, yet many can’t afford to live nearby and report social isolation and limited job opportunities. They also have the lowest rates of community service for any UC campus. Activist Kevin Norton points to state statistics linking rising housing costs to poor health for low-income people and renters. He calls on UCSC to provide more on-campus housing, slow enrollment growth and establish stronger ties between students and the wider community.

Have something to say? Lookout welcomes letters to the editor, within our policies, from readers. Guidelines here.

UC Santa Cruz students report the worst mental health of any University of California campus.

I was stunned to learn this, given the campus’s idyllic, summer-camp-like setting amid the redwoods, its ocean views and Disney-like proximity to grazing deer and wild turkeys. Yet, according to data from state surveys, Banana Slugs are the most unhappy and dissatisfied students in the UC system.

Since 2014, UCSC students have struggled more than their peers across the UC system — showing difficulty focusing on their studies and some of the highest rates of physical health problems interfering with academics. UCSC undergraduates report the most stress and depression of any campus, with two-thirds in 2024 saying that these challenges disrupted their education, according to UC Office of the President surveys.

According to UCSC’s own Healthy Campus initiative, the university “consistently ranks highest for student stress, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and drug use compared to other UC campuses.” Faculty, too, “grapple with stress and anxiety personally but also in supporting students in their classrooms.”

The numbers are sobering.

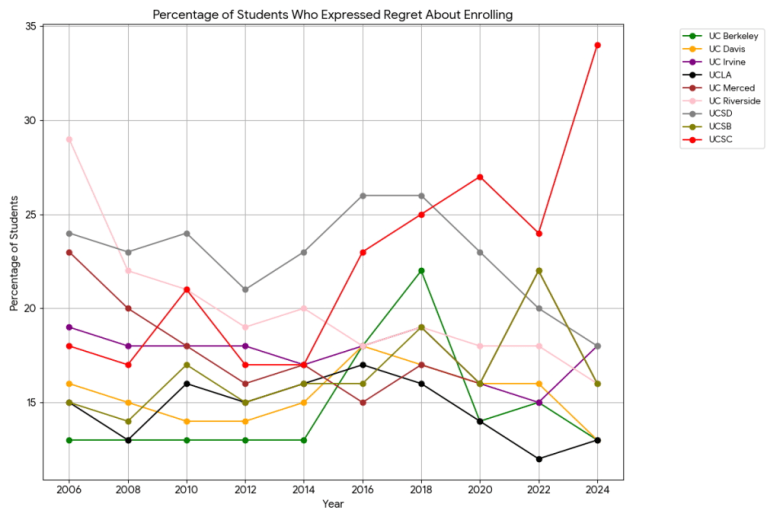

34% of undergraduates regretted enrolling at UCSC in 2024 —the highest of any UC campus by a wide margin.

40% and 38% of graduate students, polled in 2021 and 2023, respectively, felt unable to balance work and family life, the worst percentages in the UCs.

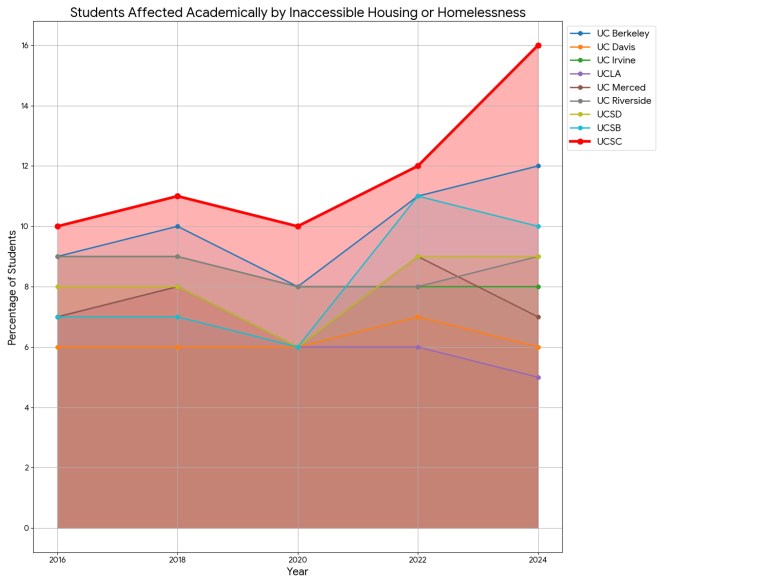

66% of undergraduates worried about paying rent in 2024, and 16% said housing insecurity interfered with their studies — again, the highest in the state.

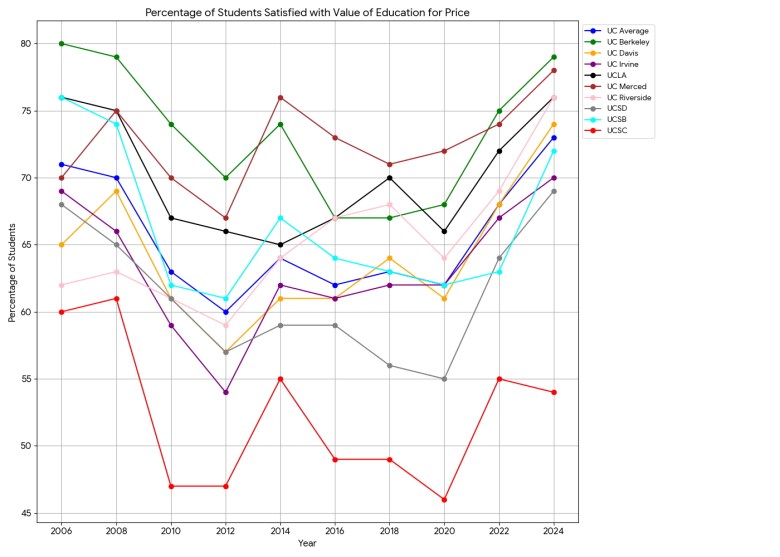

46% of UCSC undergraduates say they were dissatisfied with the value of their education last year, the highest for any campus. All UC universities have the same tuition costs.

After comparing UCSC to other universities, I believe that the primary driver of these issues is the lack of affordable housing for students.

Between 2010 and 2024, the median cost of a single-family home in Santa Cruz County nearly tripled, from $495,000 to $1.42 million. Rents skyrocketed. As a result, UCSC has the highest prices for off-campus housing for any university in California, according to the University of California Office of the President. A one-bedroom apartment near UCSC in February, averaged $3,416 per month, $663 more than in the next most expensive UC market (UC Irvine). Even with roommates, a UCSC student will pay $2,240 per month for a single room in a two-bedroom apartment, $541 more than they would pay for a similar off-campus apartment near UCLA.

That’s a stressful amount of money to be paying for rent as a college student.

“It’s a cloud that hangs over everyone’s heads,” UCSC junior David Monjaras told me. “If you’re not talking about it, you’re thinking about it.” He’s seen friendships strained by UCSC’s housing lottery, peers living in vans, and monthly rents that shock his friends and family living back home in Orange County.

A photo of an overcrowded apartment from the “No Place Like Home: Affordable Housing in Crisis, Santa Cruz County, CA” report. Credit: Via UCSC Center for Labor and Community

A photo of an overcrowded apartment from the “No Place Like Home: Affordable Housing in Crisis, Santa Cruz County, CA” report. Credit: Via UCSC Center for Labor and Community

Another disturbing number: UCSC has a large number of students who regularly report being “housing insecure” or unhoused.

Stress — and how our bodies respond to it — is a common denominator for health problems. A recent academic analysis of 23 studies, published in the BMC Public Health journal, found that stress caused by high housing costs leads to poor mental and physical health — increasing rates of alcohol use, poor nutrition, depression and anxiety — especially for low-income residents.

The university has to stop this cycle.

UCSC hasn’t built significant new on-campus housing in 20 years, partly because of environmental lawsuits, yes, but the pattern has to end. Its current project to build new units for graduate student families at the base of campus will house 120 people — 76 fewer units than the housing unit it is replacing, and will also raise the cost of rent by $527 per month.

It’s far too little.

Enrollment, meanwhile, has grown more than 16% since 2008, leading the university to convert lounges into bedrooms, cram three students into two-person dorms, and lean on overpriced public-private housing partnerships, according to a report from UCSC’s Center for Labor and Community. To make matters worse, the completion of a new on-campus housing project with 2,900 beds on Heller Drive has just been delayed until 2029-30.

Meanwhile, the University of California Board of Regents and UCSC continue to push for higher enrollment, often without the state providing extra funding. The City and County of Santa Cruz are locked in a court battle with the regents over a plan to add 8,500 students by 2040, because our elected leaders doubt the UC Board of Regents and UCSC can build enough affordable housing to support the growth.

Santa Cruz Mayor Fred Keeley recently criticized the UC regents’ approach: “They don’t treat anything else as a business, except when it comes to housing.”

The business partnerships the University of California is making with private real estate companies are also deeply disturbing. In 2023, the University of California invested $4.5 billion into Blackstone Real Estate, the world’s largest private equity firm — known for raising rents by as much as 201%. Although Blackstone doesn’t own real estate in Santa Cruz, the UC appears to have learned a few of its tricks.

In 2021, the University of California Office of Investments purchased Hilltop apartments on Western Drive (near campus), and then directed management to force out non-student residents and raise the rent. Since then, Hilltop has been plagued with complaints about staff, code violations, maintenance problems and rodent infestations. Many of the units still charge market rates, with the cost of many one-bedroom apartments ranging from $3,545 to $4,045 per month.

According to UC Chief Investment Officer Jagdeep Singh Bachher, the Hilltop and other rental properties near other UC campuses were bought “purely as investment assets, to make a return on investment for our pensioners and for those in the endowment.”

I’m saddened to see the UC treat tenants this way, because college students deserve care and respect — they are our future, after all.

Similarly, another murky housing project underway is going up at the intersection of Swift Street and Delaware Avenue. It’s a public-private partnership expected to house 400 UCSC students and 62 employees, to be finished in the fall of 2026. It’s owned by a local limited liability company, Redtree Partners, which has agreed to lease the units to UCSC for 30 years. The university said it was planning to offer rates at 20% below market rates for students and give a 5% reduction for employees. Therefore, monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment would still cost at least $2,632 for a UCSC student and $3,125 for an employee.

That’s not affordable. UCSC administrators, we can do better than that.

Data from the UC Undergraduate Experience Survey (UCUES); graphs created by Kevin Norton.

Data from the UC Undergraduate Experience Survey (UCUES); graphs created by Kevin Norton.

Of course, housing is only part of the problem.

Students also need a clear pathway from college into good-paying jobs so they can pay off the debt they’ve accrued — something harder to find in Santa Cruz than at more urban campuses like UC Berkeley, where internships, professional networks and higher-paying jobs are more accessible.

Since the pandemic, UCSC has ranked near the bottom for “overall social experience.”

Many students now live as far away as Capitola or Soquel because of high rents, commuting up to the mountaintop campus and often walking long distances once there. UCSC’s location is unique — it’s the only major California university tucked into the mountains. While the setting is beautiful and rejuvenating for many, other students told me it can feel “isolating.”

To afford living here, students often commute and work full-time jobs, leaving little time to build friendships or engage with the community. That might help explain why UCSC has had the lowest community service rates in the UC system since 2016. Only 25% of students said they volunteered off campus last year.

Let me pause now and give credit where it’s due: UCSC has invested in strong mental health support. Students I spoke with praised the Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) department, where therapists are doing remarkable work under tough circumstances. The program is well funded, and even includes a Mobile Crisis Team. UCSC is also adding 400 beds at Kresge College this year, with another 2,900 due to open on Heller Drive by 2029 or 2030.

But it’s nowhere near enough. Roughly 10,000 students still lack campus-owned, affordable housing.

The question now is: What else can we do, as we wait and push for the campus to build?

Let’s first act on what former mayor and county supervisor Ryan Coonerty recommended in a recent Lookout Community Voices op-ed. UCSC should accept more local students, who can live with family and help their out-of-town peers find social support in the community.

Next, the UCSC and the UC Board of Regents must drop plans for adding 8,500 more students in Santa Cruz by 2040, but keep investing in on-campus housing, which would vastly improve student well-being. I encourage readers to send an email to the UC regents and share your opinions.

Kevin Norton. Credit: Kevin Norton

Kevin Norton. Credit: Kevin Norton

I applaud the City and County of Santa Cruz for standing firm against increasing UCSC enrollment without adequate on-campus housing. Because of our proximity to Silicon Valley, we should require three new beds of on-campus housing for every additional student added to the census. Environmental groups, please stop preventing on-campus housing projects.

We must do more for our students – and we have to do it now.

Statewide numbers should be a wake-up call that UCSC and the wider community can do more to support the Banana Slugs — and protect them from extinction.

Kevin Norton is a public health professional who lives on the west side of Santa Cruz. He is a community organizer for Pacific for People. He can be reached at healthysantacruz@gmail.com.