Opportunities for good, steady, corporate employment have dwindled sharply in Japan since the mid-1990s, with alarming implications for future retirees. Drawing on her quantitative research, a labor expert stresses the need for both short-term fixes and long-term reforms to avert a major retirement crisis.

Breaking Down the Ice-Age Generation

The term “employment ice age” has been coined to describe the first decade or so of corporate retrenchment (mid-1990s through early 2000s) following the collapse of Japan’s 1980s asset-price bubble. Young people who completed their schooling during those years had a much harder time securing “regular” corporate jobs than their predecessors, and those struggles have had a lasting impact on their average income, savings, and cumulative pension contributions. Now in their forties or early fifties, many members of the “ice-age generation” (here, comprising all those who completed their school education between 1993 and 2004) are facing the specter of a retirement crisis, and policymakers have begun groping for a solution.

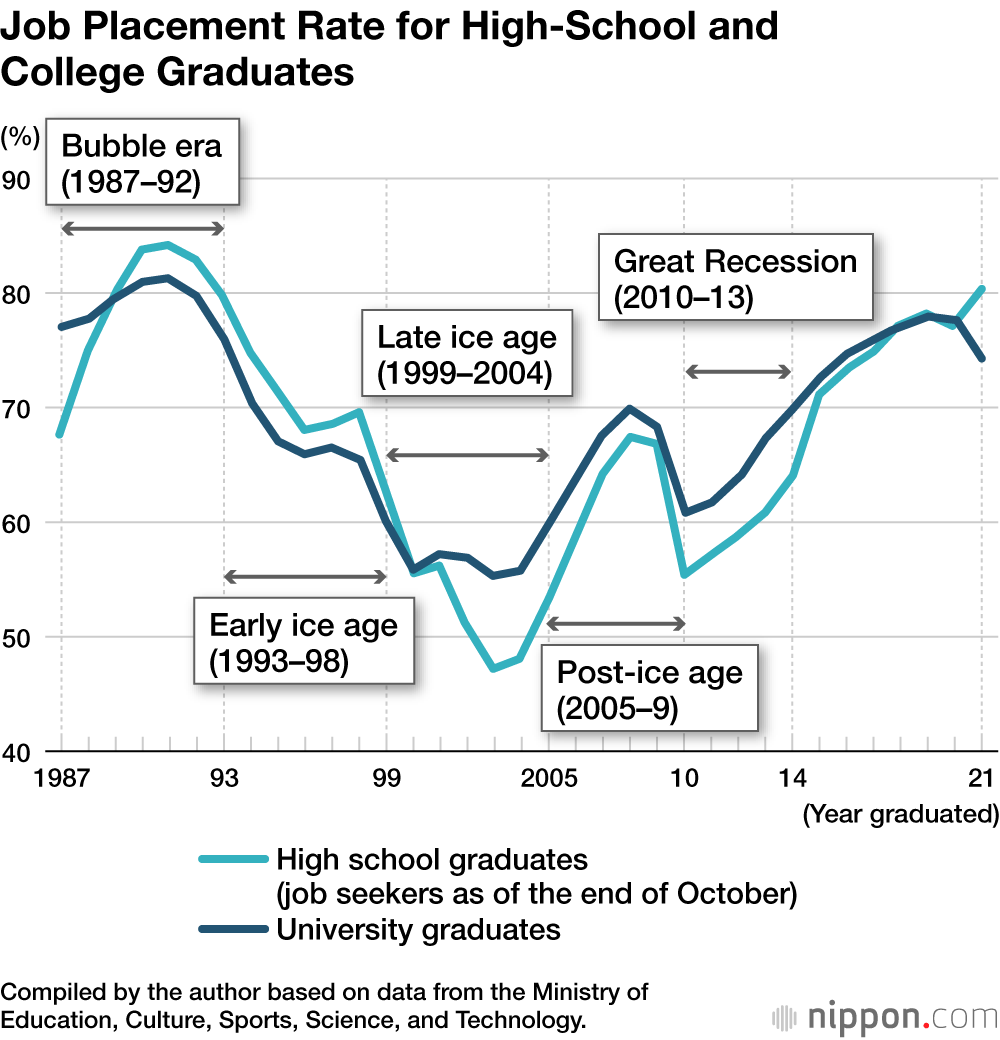

The above graph charts the job placement rate for high school students and college graduates during the period spanning 1987 and 2021. Japan’s postbubble economic slowdown began in 1991, but the class of 1993 was the first to feel the full impact, as corporations cut back drastically on their annual hiring of new graduates. Between 1992 and 1995, the placement rates for job seekers in both categories (based on job offers) fell more than 10 percentage points. This rapid cooling of the job market for new graduates gave rise to the buzzword “employment ice age.” But viewed in the context of employment trends over the next quarter century, the placement rate for job seekers graduating in the mid-nineties was not all that bad.

Corporate retrenchment intensified as a result of the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, punctuated in Japan by the 1997 collapse of Hokkaidō Takushoku Bank and Yamaichi Securities. As a result, in 1999 and the early 2000s, the job placement rate for new graduates plunged to the lowest levels recorded over the past three decades. It recovered somewhat after 2005, returning to mid-nineties levels around 2007–8, only to plunge again in 2010 amid the Great Recession triggered by the 2008 global financial crisis. (The tsunami and nuclear disaster caused by the March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake also had an effect on hiring.)

As this suggests, the blanket term “employment ice age” tends to obscure the sharp deterioration in the job market following the 1997 financial crisis. It also glosses over the struggles of those graduating during the Great Recession, a period not typically included in the employment ice age. To facilitate a more precise analysis of employment trends from the late bubble economy on, I have grouped those who graduated between 1987 and 2013 into five cohorts based on the year of graduation:

1987–92: Bubble-economy cohort

1993–98: Early-ice-age cohort

1999–2004: Late-ice-age cohort

2005–9: Post-ice-age cohort

2010–13: Great Recession cohort

By the Numbers

Comparing the men in these groups, we find that both the rate of regular employment and the average annual income (for high school and college graduates alike) are highest in the bubble-economy cohort, second-highest in the early-ice-age cohort, and lowest in the remaining three cohorts, which do not differ from one another significantly. Among women in general (including those who are not employed), the rate of regular employment and the average annual income both increase with successive generations because more women are continuing to work after they marry and have children. However, if we limit the scope of analysis to women working full-time, we discern the same trend as that noted among men. In addition, intracohort income inequality grows as we progress from the bubble-economy cohort to the early-ice-age and late-ice-age cohorts and plateaus from then on.

There is a tendency to associate the employment ice age with the job-hunting struggles of university graduates during that period, but in fact unemployment and nonregular employment rose more sharply among high school graduates than college graduates. The following tables display employment data for the first four cohorts of high school graduates. The Great Recession cohort is excluded because the corresponding data are not yet available.

The figures show that, over the long term, regular-employment rates and average annual incomes declined among early-ice-age male high school graduates and stagnated among the next two cohorts. The statistics also show a continuous increase in the percentage of young male high school graduates classifiable as NEETs (not in education, employment, or training) 6–10 years after graduation. The NEET category in Japan encompasses young people (15–34), mostly unmarried, who are out of school but neither employed nor actively searching or training for a job (excluding those occupied mainly as homemakers). Among men, the long-term rates of unemployment and nonregular employment are lower for college graduates than for high school graduates, but the trend lines are basically the same in both groups.

Employment Rates and Average Annual Income Among Male High School Graduates 10–12 Years after Graduation

Percentage of NEETs Among Male High School Graduates 6–10 Years After Graduation

Percentage of Male High School Graduates Aged 35–39 Who Are Unmarried, Without Steady Employment, and Living with Their Parents

Source: Compiled by the author from data published in the Statistics Bureau’s Labor Force Survey.

It was not possible to gather data on the percentage of post-ice-age cohort members aged 35 to 39 who were unmarried, without regular jobs, and living with their parents, but figures for the bubble-economy, early-ice-age, and late-ice-age cohorts reveal a continuous increase. Corresponding data for women have been excluded from the table because the employment status of Japanese women is so dependent on their family situation. But among women as well, the percentage of NEETs rises among the younger cohorts. The portion of women who are unmarried, lacking steady employment, and living with their parents holds more or less steady among college graduates but rises among high school graduates.

Looming Retirement Crisis

Unmarried adults who are living with their parents for economic reasons are obviously at relatively high risk of becoming impoverished when their parents can no longer support them. Many self-supporting ice-agers are also at risk, not only because of their relatively low incomes but also because they were excluded for too long from the Employees’ Pension Insurance system (EPI), which supplements Japan’s meager Basic Pension benefits.

The growing number of “freeters”—young people supporting themselves with free-lance work, part-time jobs, and short-term gigs instead of securing regular employment after graduation—first emerged as a public issue in the late 1990s. Initially, this trend was attributed to changing values, but it seems clear in retrospect that the increase in nontraditional workers among members of the ice-age generation is tied to the loss of traditional job opportunities. In the post-bubble years, many companies began relying more heavily on free-lance workers and nonregular employees as a way to meet their labor needs while saving on social insurance costs. As a rule, free-lance, short-term, and part-time workers were not enrolled in EPI, under which employers pay half of the contributions. Without this supplementary pension, retirees must make do with the Basic Pension, which is inadequate to live on. Accordingly, unless the pension system is modified, the portion of seniors struggling to get by on inadequate benefits is sure to grow.

Under Japan’s social security system, elderly households that find themselves in such a situation have only public assistance (welfare) to fall back on. Already, the elderly account for more than half of all households receiving public assistance in Japan. Barring a major pension reform, that percentage will grow quickly.

This is not the purpose for which public assistance was intended. The purpose, according to the Public Assistance Act, is to “promote self-support” while providing assistance to those living in poverty on the condition that they “utilize [their] assets, abilities, and every other thing available to [them] for maintaining a minimum standard of living.” The program was not designed to supplement the incomes of elderly persons who have no prospects for achieving economic independence in the future. The more it is relied on for this purpose, the greater the burden on government finances. Public assistance (unlike the pension insurance system) is funded entirely by tax revenues. Furthermore, owing to the government’s strict eligibility requirements, the application and screening process is elaborate and time-consuming, making public assistance an inefficient way of supplementing old-age pensions.

This is why the government needs to formulate effective measures to manage the looming retirement crisis before the members of the ice-age generation reach old age.

Inadequate Policy Response

On June 3, 2025, a ministerial council dedicated to this issue submitted a “basic framework for new programs to support the ‘employment ice age’ generation and others.” However, the only concrete proposals for relief involve expanding employment opportunities for older individuals (up to age 70), opening up EPI to part-time workers, and moving quickly to exempt Basic Pension benefits from the “macroeconomic slide” mechanism, which limits cost-of-living increases.

Measures designed to lengthen the pension contribution period by enabling people to stay on the job longer and making part-time workers eligible for Employees’ Pension Insurance may help to prevent a similar crisis among the post-ice-age and Great Recession cohorts, but they will not have much effect on the ice-agers, who are already between their mid-forties and early fifties.

The time has come to consider a new way of supplementing low retirement benefits. The government already has a system of subsidies for low-income retirees, but the scope is quite limited, and the subsidies are small. One option would be to beef up and expand this program. Another would be to adopt a minimum guaranteed pension.

Of course, financing such a benefit will be a challenge, but if nothing is done, the government will end up pouring more and more funds into public assistance. The burden on public finances will ultimately be lighter if we move proactively to avert a crisis.

Toward Wholesale Reform of the Pension System

A more fundamental problem is the basic design of the current pension system, which was created with just two types of households in mind. One type is that headed by a full-time salaried corporate employee, who enrolls in the partially-employer-funded EPI. The other is the self-employed household, which enrolls in the National Pension as a married couple. The system is not properly equipped to deal with people engaged in other modes of employment.

In recent years, the Diet has passed laws to make more nonregular workers eligible for EPI. Further expanding eligibility to part-time employees would take such reforms a step further. But it would still leave uncovered a broad swath of nontraditional workers, including people who work under outsourcing contracts and those who juggle multiple jobs. The diversification of working styles may have accelerated in the 1990s, but it has emerged since then as a long-term trend, and there is an urgent need to adapt the social security system to this new reality.

That said, Japan’s pension system is already under strain owing to the rapid aging of the population, a trend that is projected to continue for many years to come. Under the circumstances, raising the average level of old-age pension benefits across the board could be prohibitive. That being the case, it would be worthwhile for policymakers to consider redistributive measures to reduce the income gap between high-benefit and low-benefit retirees. This might be accomplished by increasing the weight of the Basic Pension relative to the compensation-tied EPI benefit. Another possibility would be to institute a mechanism within the pension system to fund supplementary benefits for low-income retirees.

Some have argued against such a change on the grounds that it is inconsistent with the basic principle of social insurance, in which the benefits one receives depend on the amount one pays in. Others have suggested that it would rob society’s productive members of their incentive to work and build their assets. Such potential drawbacks are among the matters to be considered as we deliberate wholesale pension reforms going forward.

Scrap the Category 3 Exemption

Another target of reform should be the anachronistic category 3 exemption, which allows EPI enrollees’ dependent spouses (including those working part-time) to receive Basic Pension benefits without paying into the National Pension system. While Japan’s overall marriage rate has been declining, the rates are higher among younger men and women who enjoy economic security, and this disparity has continued to grow. There have been many calls for elimination of the category 3 exemption on the grounds that it discourages married women from working full-time. But an even more fundamental problem, in my view, is the regressive nature of the current setup, which advantages a household headed by a regular employee over one struggling with nonregular employment or joblessness.

Given the nature of the pension system, in which benefits are based on the insurance premiums paid over a lifetime, fundamental changes will need to be phased in gradually. Moreover, such systemic reforms must be meticulously designed from the outset to avoid internal conflicts and inconsistencies. In short, a fundamental reform of the pension system will take time. Policy makers and stakeholders must be prepared to engage in extended dialogue, unswayed by short-term political pressures.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 7, 2025. Banner photo: Students at a jobs fair in Tokyo Dome held in September 1995, during Japan’s postbubble “employment ice age.” © Jiji.)