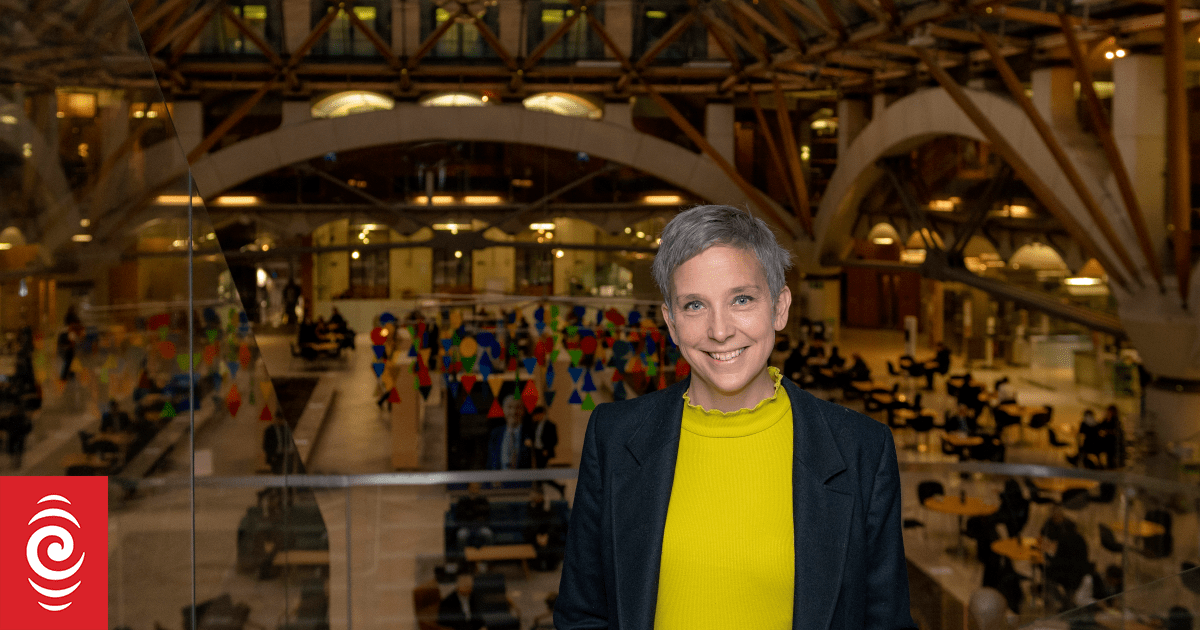

Climate scientist Dr Tamsin Edwards has contributed to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report and is about to begin working on her seventh.

Photo: Supplied

It’s not something many of us are born with, being okay with uncertainty.

Climate scientist Dr Tamsin Edwards has made it her day job.

She’s listed among hundreds of authors from all over the world on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report, and is about to begin work on the seventh. She’s given climate change talks at Glastonbury, and appears on the BBC Radio 4 podcast “39 Ways to Save the Planet”.

That, she says, is one of the things she’s most proud of – giving people tangible solutions to help the planet, and ease that sense of dread.

She’s in New Zealand this month to give this year’s S.T. Lee Lecture, on the topic of uncertainty around sea-level rise in Antarctica.

“How do we figure out what our error bars are on our predictions? If we’re trying to think about the future, what’s the range of different possible futures that we might face?”

Despite New Zealanders’ affinity with the great white continent, Edwards explains scientists now think far-off places like Greenland are more likely to affect sea-level rise around our shores.

“When you lose ice from Antarctica, the local sea level right around Antarctica actually goes down because it’s no longer pulled up by the sort of gravitational attraction of the ice sheet,” Edwards says.

“Instead, when that water goes into the global oceans and gets spread around, it affects maybe the northern hemisphere more. So [New Zealand] would be affected by Greenland more.”

Sea level rise is “a very complicated area of science”, she says. “It’s lots of different disciplines working together.”

Communicating all of the different aspects of the public, even to other scientists, can be quite complicated. Small changes in averages – average sea level rise, average global temperature – can translate into huge changes in extreme weather and coastal flooding.

“If you increase sea levels globally by perhaps half a metre, that doesn’t sound much, right? You just think, oh, half a metre, that’s knee level – you wouldn’t think that would be too bad.

“But the knock-on effect on coastal flooding can make it hundreds of times more likely to flood. A one-in-100 year event suddenly becomes something that could happen every year.”

An iceberg floating in front of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Photo: AFP / Claudius Thiriet

She says she feels a responsibility to communicate uncertainty. Science is not a book of facts but a living body of knowledge, constantly evolving.

“I think it’s really important to say, ‘Well, look, we can’t know everything, some things are hard to pin down, but here’s the stuff we are confident about’.

“Maybe we know the direction of travel, but we don’t always know how quickly we’re going to get there.”

The Paris Agreement set a target to limit warming to 1.5 degrees – does Edwards think that’s still possible?

“I think it was always going to be really difficult,” she says – but she urges people not to think of it as a cliff-edge.

“It’s not something where we say, okay, if we get to 1.6 degrees of warming, everything is burning, everything is extinct,” she says. “But at the same time, we’re already seeing effects on our weather at 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 degrees. So it’s important to limit warming.”

With 15 years of science communication up her sleeve, she’s discovered most people aren’t motivated by fear – they need to know they can still make change.

The early days of discourse concerning climate change were “scary”, she says, punctuated by verbal attacks on twitter, gendered abuse, and public disagreements between scientists: “Should we be talking about uncertainty or should we be focusing just on certainties?”

“The conversation has really moved away from that,” Edwards says. “Climate science and the need to act on climate change is mainstream.”

“It almost feels like if you were pushing on a door really, really hard and then suddenly someone opens it and you kind of fall in the room,” she laughs.

When it comes to making change, she says people should never underestimate the value of pester power. “Think about how you can push on the levers of other people who are more powerful than you.”

She’s expecting work on the seventh IPCC report to be intense, just as it was with the sixth, published in 2023.

“And what people probably don’t realise is that when we work on the IPCC reports, it’s completely voluntary,” she says. “There were times I was doing maybe a 50 hour week of teaching and 20 hours on the IPCC over the weekend.”

Each chapter could have thousands of review comments, and everything needed to be considered, answered, and potentially included in the copy.

“It was quite a spreadsheet,” Edwards says.

The seventh report is due out in 2029, and work is already underway to engage hundreds of experts and divide their collective knowledge neatly into chapters, in one of the biggest collaboration efforts in science.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.