The Global Technical Strategy for Malaria calls for at least a 75% reduction by 2025 compared with 2015 [1]. However, the global tally of malaria deaths reached 597,000 deaths in 2023 compared to 586,000 in 2015 [2, 3]. In 2023, Uganda reported approximately twelve million malaria cases and 2793 deaths and was the third-largest contributor to global malaria cases and the tenth-largest contributor to malaria-related deaths [3]. Severe malaria represents approximately 15–20% of hospital admissions in the country [4]. In 2023, Uganda recorded about 700,000 hospitalized malaria cases, accounting for roughly 6% of the total malaria burden. This is nearly three times the global average [3], noting that the global figure indicates between 1 and 3% of uncomplicated malaria cases were assumed to have moved to the severe stage of disease, and 50–80% of severe cases were assumed to have been hospitalized [3, 5]. Moreover, Health Malaria Information System (HMIS) data of Uganda indicates that 5–8% of children discharged (depending on age) will die within 6 months of discharge and most of these deaths occur at home.

The important queries are why hospitalization rate of malaria cases in Uganda is high, and what are the malaria deaths drivers?

Delayed treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases is a major contributor to disease progression to severe form that as medical emergency needs urgent inpatient case management services [6, 7]. Consequently, severe malaria may result in complications, or death. Literature confirmed that seeking health care within 24 h of onset of illness is a serious gap in Uganda [8,9,10]. Moreover, delays in initiating injectable artesunate in severe malaria cases and delays in managing severe malaria complications significantly contribute to malaria deaths in the country [11].

A total of eleven African countries, including Uganda, account for about 68% of malaria deaths that are part of the “High Burden to High Impact” (HBHI) initiative aimed at accelerating progress against the disease [3]. In March 2024, ministers of health from the HBHI African countries committed to ending malaria deaths in the Yaoundé Declaration [3]. In line with the Yaoundé Declaration, Uganda launched the “24.2 Hours Initiative” in April 2025 to strengthen malaria case management services and to address drivers of delayed treatment (Fig. 1).

Launching ceremony of the “24,2 Hours Initiative”, April 2025. https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/news/ugandas-242-hours-initiative-game-changer-malaria-mortality-reduction)

This perspective article presents existing evidence in the literature covering both malaria case management gaps in Uganda as well as relevant solutions to achieve reduction of malaria mortality and accordingly proposes a strategic framework called the “24,2 Hours Initiative”. The principles guiding the initiative may be applicable to other high-endemic regions, including sub-Saharan Africa, if they are adapted into locally tailored interventions.

Continuums of malaria case management services

Malaria case management, consisting of quality assured early diagnosis and prompt effective treatment, remains a vital component of malaria control and elimination strategies [12]. Malaria case management as a key part of universal health coverage should be available throughout the country and to everyone [1, 3, 12]. Malaria case management services should cover following patient categories: suspected malaria, confirmed uncomplicated malaria, severe malaria and discharged severe malaria patients from hospital. This category forms the basis of the “24,2 Hours Initiative” (Fig. 2).

Targeted patients of malaria case management services

Review of Uganda malaria case management

This section presents the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and literature findings regarding gaps in Uganda malaria case management strategy as well as lack of adherence to WHO and national guidelines.

Suspected and confirmed uncomplicated malaria

The WHO emphasizes on prompt and appropriate diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases within one day of the onset of malaria symptoms [7, 13]. Nevertheless, evidence from the literature shows delayed healthcare-seeking, delayed treatment of malaria cases, and low treatment coverage in Uganda [8,9,10]. Based on Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey 2019, only 57% of children under five with fever sought treatment within 24 h from the onset of fever and only 64% of children with fever, received any anti-malarial treatment [14]. Across different studies, delays in receiving malaria treatment beyond 24 h from symptom onset ranged from 41% to about 80% [8, 9, 14], with longer delays observed in rural areas [14]. Unfortunately, rate of prompt treatment within 24 h in many African countries is also low [14, 15], despite this fact that the people expose frequently to Plasmodium infections [15].

Additionally, universal access to quality malaria care remains a challenge in Uganda. Over 50% of malaria cases are managed through the private sector or self-medication, largely due to overcrowded public health facilities and frequent stockouts of essential antimalarial drugs [16].

Severe malaria

Severe malaria is a medical emergency that requires urgent treatment. The WHO emphasizes that parasitological diagnosis should be made available to healthcare providers within two hours to ensure the appropriate choice of antimalarial drugs and dosing. To avoid delays in treatment, in suspected severe malaria cases where parasitological diagnosis is unavailable or delayed, the WHO recommends initiating treatment based on clinical suspicion [6]. The WHO also recommends that where complete treatment of severe malaria is not possible, patients should receive a first dose of one of the recommended prereferral treatments, preferably via the parenteral route or if not feasible, for children under six years old intrarectally, unless the referral time is very short [6, 7, 12, 17, 18].

Delays in treatment of severe malaria cases in Uganda have been reported by the literature. Accordingly in the studies population, a range of 25 -71% of hospitalized severe malaria cases delayed initiating injectable antimalarial drugs by at least one calendar day [11, 19, 20], and only 37% of the children with danger signs visited community health workers (CHWs) within 24 h of onset of illness [10]. Additionally, reported proportion of eligible severe malaria cases who received a dose of prereferral rectal artesunate varied from 55 to 73% [21, 22].

Discharged malaria cases from hospital

The WHO recommends that children admitted to hospital with severe anaemia living in settings with moderate to high malaria transmission can be given a full therapeutic course of an antimalarial drugs at predetermined times following discharge from hospital to reduce re-admission and death [17]. Administration of post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PDMC) is endorsed in the national malaria treatment guidelines (NMTGs). While the prevalence of readmission with severe malaria among children under 5 years of age was reported around 27% [23], but, based on HMIS, a majority of children were not administered PDMC.

Adherence to WHO recommendations and national guidelines

Adherence to WHO and the NMTGs recommendations in Uganda is sub-optimal [22, 24]. A study results showed that approximately one in three children under five with fever receiving substandard care [25]. The literature has identified gaps in adherence to the NMTGs for both suspected and confirmed uncomplicated malaria cases. These gaps include delays in seeking care, incomplete treatment, self-medication, administration of antimalarial drugs without diagnostic testing, and the consumption of substandard or fake antimalarials. Substandard and fake antimalarials pose significant health and economic risks, disproportionately affecting poor and rural populations and contributing to health inequities in Uganda [26, 27].

Poor adherence to treatment guidelines can lead to suboptimal health outcomes, diagnostic challenges, treatment failure, and irrational use of antimalarial drugs. Addressing these issues is, therefore, a top priority [24, 28,29,30,31,32]. Notably, more than 50% of malaria cases in Uganda receive treatment from private sector and drug shops. This is important given reported quality issues of case management services and poor adherence to the NMTGs in private sector was higher in the literature [25, 33,34,35,36,37,38]. Studies results showed that drug shops frequently provided sub-optimal care, which contributed to inappropriate use of antimalarial drugs and delays in accessing appropriate treatment [34, 39]. Moreover, many private drug outlets clients receive antimalarial medicines without proper diagnosis or prescription, only a minority obtain quality-assured treatments, and the availability of non-WHO-prequalified artemisinin-based combinations has risen in recent years [38, 40].

Quality issues is not limited to uncomplicated malaria cases. Study results confirmed that the quality and coverage of severe malaria case management services in health system in Uganda require improvement. Based on literature, fewer than the recommended three doses were administered in around one fifth and delays were common in around two third of severe patients [20].

Adherence to severe malaria treatment guidelines for children in regional referral hospitals has been reported as poor and requires improvement [20]. Only 44.5% of severe malaria cases in Uganda received both a parenteral antimalarial drug and oral artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) [22]. Besides, most severe malaria cases who received prereferral RAS did not receive appropriate after-referral treatment [41]. Evidence from the literature shows that the effectiveness of pre-referral rectal artesunate in Uganda is limited by poor access to quality post-referral care [22, 41, 42]. Additionally, many children with severe malaria do not complete either pre-referral or post-referral treatment, and referral compliance rates remain low [41,42,43].

The literature highlights the following drivers of suboptimal adherence and poor-quality services:

Low capacity of CHWs to identify danger signs of severe malaria negatively affects the effectiveness of severe malaria care [44].

Frequent stock-outs of essential malaria diagnostics and medicines in Uganda highlight weaknesses in supply chain management and contribute to lower than expected use of CMCM and public health services [21, 25, 45, 46].

Care-seeking behaviour among malaria patients and their caregivers is suboptimal. Communities in malaria endemic areas often lack awareness of fever as an important malaria warning sign [34, 39, 47]. A study also revealed widespread misperceptions about malaria risk, contributing to under-treatment [48].In addition, caregivers frequently fail to recognize danger signs of severe malaria and may underestimate early symptoms, leading to delays in seeking timely and appropriate treatment [39, 49].

Poverty, limited access to quality-assured free services, and low health literacy remain major barriers to treatment compliance [50]

There are gaps in the monitoring and evaluation of case management services that require strengthening to ensure effective oversight and improved service delivery [21, 51].

The “24,2 hours initiative” and its components

This section presents the strategic interventions, results chain, and implementation approach of the ‘24,2 Hours Initiative.

To address detected gasps in malaria case management strategy in Uganda, the “24,2 Hours Initiative” was launched in April 2025. The “24.2 Hours Initiative” highlights the need for timely access to and use of quality-assured case management services to maximize impact within the critical “golden” time frame.

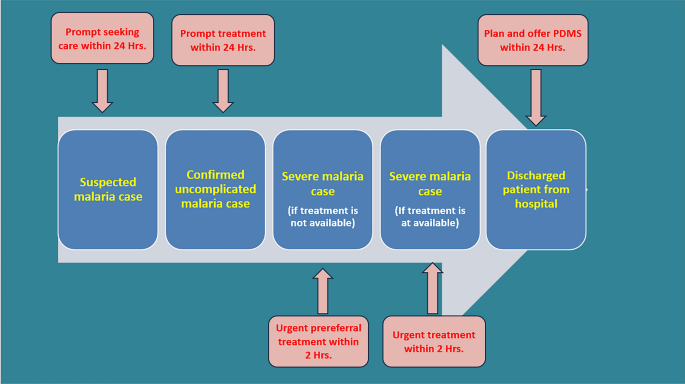

The “24,2 Hours Initiative” components include (Fig. 3):

a)

care-seeking by suspected malaria cases within 24 Hours.

b)

prompt diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases within 24 Hours.

c)

urgent prereferral treatment of severe malaria cases by injectable artesunate (or rectal artesunate for children under six years old when injectable artesunate is not available) within 2 h of arrival in a setting that quality assured severe malaria case management is not available.

d)

urgent treatment of severe malaria cases by recommended injectable antimalarial drugs within 2 h of arrival in a setting that quality assured severe malaria case management is available).

e)

Initiate post discharge services of discharged severe malaria patients within 24 Hours after discharge.

The “24,2 Hours Initiative” components

Expected results of the “24,2 hours initiative”

The “24,2 Hours Initiative” has been designed in line with Results-based Management Approach. Table 1 presents expected results (results chain) of the initiatives and Table 2 presents its strategic interventions.

Table 1 Expected results of the “24,2 Hours Initiative”Table 2 Strategic interventions of the “24,2 Hours Initiative”

Post-discharge malaria services (PDMS) aim to ensure continued recovery and prevent recurrence among recently hospitalized malaria patients. These services typically include completing treatment with injectable artesunate followed by an oral ACT regimen, scheduling post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PDMC) at predetermined intervals for eligible patients as per WHO guidance, and providing long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs). In addition, PDMS involves conducting follow-up blood slides to monitor parasite clearance and educating patients or caregivers on correct LLIN use, adherence to medication, recognition of danger signs, and the importance of timely care-seeking in case of recurrent symptoms.

Impact of the 24.2 hours initiative on effective coverage of malaria case management services

In 1978, Tanahashi introduced a model for assessing health service coverage by identifying operational bottlenecks, analysing their causes, and guiding service improvements [52]. The model elements are:

Availability refers to the presence of essential resources such as staff, facilities, and medicines.

Accessibility means that services must be within reasonable reach of the intended users.

Acceptability indicates that services should align with users’ expectations and social norms; factors such as cost and cultural beliefs can influence this.

Contact coverage refers to the actual interaction between users and providers, which does not always guarantee a successful outcome.

Effective coverage means that users receive services that adequately address their health needs.

Table 3 presents the impact of the 24.2 Hours Initiative on enhancing effective coverage of malaria case management services. Table 4 presents indicators to measure the progress of the initiative.

Table 3 Impact of the “24.2 Hours Initiative” on Enhancing Effective Coverage of Malaria Case Management Services using Tanahashi modelTable 4 the “24,2 Hours Initiative” monitoring and evaluation of indicatorsImplementation approaches for the “24.2 hours initiative”

The implementation rate of routine interventions under Uganda malaria case management strategy remains low, primarily due to limited programme management capacity at the subnational level and insufficient resources [26].

To strengthen the translation of “24.2 Hours Initiative” planned interventions into practice, and enhancement of effective coverage of case management services the following approaches will be adopted:

To enhance accountability in implementing planned activities, the initiative is aligned with the RBM framework, incorporating regular and robust monitoring and evaluation [53]. Accordingly, intended results will be defined at national, district, and health facility levels, and a dedicated dashboard will be established to track and report both implementation rate and actual results achieved at each level. For the first time, new indicators have been introduced under the initiative to monitor the entire results chain, including outputs, outcomes, and impacts.

The RBM approach will be useful to improve the quality of care by measuring relevant indicators and providing solutions to address identified gaps. It will also promote compliance with Value for Money (VFM) principles, including economy, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, and ethics, by ensuring transparency, enabling resource tracking, and guiding resource allocation based on prioritized results [54].

Furthermore, RBM will support studies to generate evidence for advocacy, domestic resource mobilization, and increased political commitment. It will also foster organizational and individual learning and strengthens risk management that are key elements for successful implementation.

The planned interventions will be integrated into other health services and relevant public and private sector activities at the community level, such as school-based programmes. For instance, social mobilization and behavior change communication (SBC) messages may be disseminated via mobile networks, local radio stations, or student engagement.

Strengthening subnational capacity

The recruitment of malaria case management focal points at the regional level is a key component of the initiative to strengthen subnational capacity and enhance coordination.

Moreover, strengthening the supply chain management of essential medicines and commodities for malaria case management is a key intervention under the initiative, aimed at preventing both stock-outs and overstocking.

Communities will be empowered and actively engaged through expansion of CHWs programmes

SBC&SM interventions will promote timely care-seeking among individuals with suspected malaria, both uncomplicated and severe cases, as well as among patients recently discharged after inpatient malaria treatment. Besides SBC&SM will promote adherence of malaria cases to the NMTGs. SBC&SM activities will be implemented through face-to-face engagement by CHWs, integration into school curricula, and dissemination of messages and materials via public and private sector channels. SBC&SM materials will be adapted to local cultural contexts to ensure relevance and effectiveness.

The impact of SBC&SM on behaviour change will be monitored through malaria indicator surveys, other population-based health surveys, and school-based assessments.

For the first time, a social marketing approach has been integrated into malaria case management through this project. Social marketing is an approach that applies marketing principles, alongside other strategies, to influence behaviours that improve individual and community health for the greater social good. Within the context of malaria case management, social marketing involves using research, best practices, theory, audience insights, and stakeholder engagement to design and implement programmes that promote effective malaria diagnosis and treatment. These interventions are tailored to specific audience segments, are sensitive to competing behaviours or messages, and are designed to be effective, efficient, equitable, and sustainable [55].

Improving the quality of care across the entire continuum of malaria case management, from community level services provided by CHWs to advanced care at referral hospitals, is a core intervention of the initiative given quality issues in malaria diagnosis and treatment. A comprehensive quality assurance system will be established for both diagnostic and treatment services. Besides, independent quality audits will be conducted in collaboration with professional medical boards, such as the Uganda Pediatric Association.

Currently, gaps in quality of care are driven by insufficient competency among service providers, stock out of essential medicines and supplies, and weak monitoring and evaluation system. To address these challenges, the initiative has prioritized capacity building for service providers and the strengthening monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and health information management system. The initiative also supports the distribution of up to date guidelines and tools complemented by training, continuous mentorship, and integrated supportive supervision It also ensures the provision of adequate stocks of essential antimalarial drugs and commodities, reinforces communication and behavior change strategies.

Additionally, a malaria laboratory accreditation system will be launched, including competency assessments for hospitals and health facilities managing severe malaria cases. This system will be expanded to all health facilities as well. The quality assurance and accreditation framework will be integrated with existing mechanisms, such as hospital accreditation programmes, with a focus on meeting essential medicines and supplies requirements. This integrated approach is designed to minimize cost implications and ensure sustainability in low-resource settings.

Literature evidence supporting the “24.2 hours initiative” strategic interventions

This section summarizes literature evidence supporting the proposed strategic interventions of the “24,2 Hours Initiative”, with a focus on their importance, feasibility, effectiveness, and acceptability.

The importance of prompt treatment of uncomplicated malaria

The “24,2 Hours Initiative” emphasizes on treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases within 24 h of onset of symptoms that is in line with WHO recommendations [12, 56]. Early detection and prompt, and effective treatment is a fundamental strategy in malaria control and elimination programmes across all transmission settings, including high-endemic areas [12, 56, 57]. The advantages of prompt treatment for uncomplicated malaria can be categorized at both the individual and community levels.

Prompt malaria treatment is a critical public health strategy that protects the wider community by reducing malaria endemicity and limiting the spread of drug-resistant strains [6]. Increasing treatment coverage in low and moderate transmission settings is associated with reductions in both malaria incidence and mortality rates [58]. Good access to case management, and a strong surveillance system are key factors in sustaining progress along the pathway to elimination. These elements are also considered prerequisites for implementing a combination of endemicity and vulnerability reduction measures [59]. Moreover, they can influence the likelihood of a rebound and the time it takes for incidence and prevalence to return to previous levels [60]. Findings from various studies have demonstrated the impact of early diagnosis and community treatment in lowering the burden of malaria infection in high transmission areas across SSA countries [61].

Additionally, prompt, and effective treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases helps reduce endemicity, which can be measured by the entomological inoculation rate [57]. The WHO has confirmed that strengthening diagnosis and treatment across all settings contribute to reducing malaria transmission, morbidity, and mortality. Moreover, WHO has also warned that expanding access to prompt diagnostic testing and treatment, as an effective strategy to reduce transmission intensity, has lagged behind vector control efforts [1, 6].

Prompt and effective treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases directly and indirectly lowers malaria-related mortality [57]. Even in populations with low levels of immunity, timely treatment has shown to reduce the incidence of severe disease and associated mortality [57].

It should be noted that Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte maturation in the bone marrow takes approximately 10–12 days. On average mature gametocytes appear in peripheral blood after 14 days [62]. Initiating treatment for new falciparum malaria cases within 14 days of symptom onset prevents transmission from the patient to mosquitoes. Even prompt treatment of P. falciparum and non-falciparum malaria cases with mature gametocide in the blood can reduce likelihood of transmission.

At individual level, prompt treatment of uncomplicated malaria within 24 h prevents progression to severe disease [6, 7], reduces complications and mortality [57, 58], shortens hospital stays, lowers the need for blood transfusions and decreases the risk of malaria readmission [6, 23, 63].

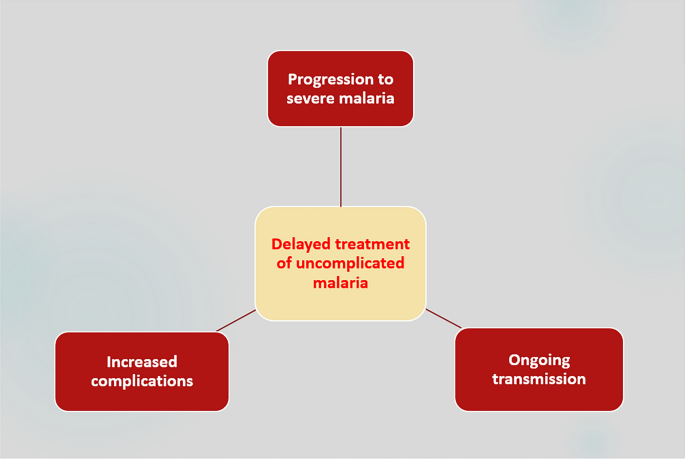

Conversely, delayed treatment of non-falciparum malaria can result in severe illness, increased complications, and sustained transmission (Fig. 4).

Consequences of delayed treatment of non-falciparum malaria

Delayed treatment of uncomplicated malaria significantly increases the risk of progression to severe malaria [7, 12, 63,64,65]. In children, delays in seeking treatment for severe malaria are a key predictor of serious complications such as anaemia, kidney injury, and cerebral malaria [63, 65, 66]. These complications contribute to recurrent hospitalizations and to prolonged hospital stays, defined as admissions lasting more than five days [63, 66]. Prolonged hospitalization was observed in 21.2% of children under 12 years with severe malaria [67]. Evidence also suggests that treatment delays are associated with longer hospital stays [63]. In Uganda, seeking care 12 h after fever onset significantly associated with readmission [23].

Moreover, severe malaria in children imposes a significant economic burden on the providers and households [68].Therefore, timely treatment to prevent severe malaria complications can also avoid excessive costs to health providers, and households [64, 69].

The importance of urgent treatment of severe malaria

The WHO has emphasized that severe malaria is a medical emergency. The WHO recommends initiating treatment of severe malaria cases with injectable artesunate within two hours of a patient presenting at a health facility. With prompt, effective severe malaria case management services the mortality rate can be reduced from 100% to 10–20% [3, 12].

In line with WHO guidelines, the “24,2 Hours Initiative” emphasized the urgent treatment of severe malaria cases within two hours [12]. Delayed treatment of severe malaria greatly increases the risk of death, with the highest risk occurring within the first 24 h [18]. In Rwanda, the possibility of mortality increased by almost four times in severe malaria cases who delayed consultation by a day compared to those who came in early [70].

Literature evidence supporting pre and post referral treatment

Pre referral and post referral treatment and effective connection between them are key components of the “24,2 Hours Initiative”.

Pre-referral rectal artesunate has been shown to improve outcomes in severe malaria [71]. A randomized trial reported a 26% reduction in overall mortality with the use of pre-referral rectal artesunate, however, the magnitude of this protective effect varied significantly by duration of referral delays [21, 72]. It was claimed that pre-referral treatment reduces the risk of death or permanent disability by up to 50%, although many studies reported much lower rate of cure in settings with after-referral poor case management services [73, 74].

The acceptability of rectal artesunate among both caregivers and CHWs has been encouraging. Integration of rectal artesunate into community care sites has proven effective, feasible and acceptable [42, 44, 72, 75, 76]. In hard-to-reach communities in Zambia, provision of rectal artesunate by CHWs to young children with severe malaria was found to be feasible, safe, and effective [77].

Literature evidence supporting PDMS

A trial conducted in Uganda demonstrated that the use of PDMC resulted in a 77% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 55% reduction in all-cause hospital readmissions within six months after discharge [78].

Literature evidence supporting SBC&SM

When well designed and effectively implemented, SBC&SM strategies and community health education have been shown to improve patient adherence to the NMTGs and reduce malaria-related child mortality [79, 80].

Literature evidence supporting free CMCM

Malaria is concentrated in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities mainly in rural and suburban settings [12, 81], Notably, 89.0% of hospitalized children with severe malaria were village residents, highlighting the vulnerability of rural population [9]. Result of a study in Uganda showed that children from rural households were statistically more likely to receive prompt and appropriate treatment with ACT than their semi-urban counterparts [82]. Therefore, expanding CMCM by CHWs to include all age groups in rural and peri-urban areas, as a fundamental strategy of the ‘24.2 Hours Initiative’, ensures equitable access to prompt, high-quality malaria diagnosis and treatment for the poorest and most vulnerable populations.

Moreover, literature evidence revealed that caregivers’ treatment choices are often influenced by the availability and accessibility [83, 84]. Distance from the nearest health facility is a key factor shaping whether and how promptly caregivers seek appropriate care [34]. Seeking care at a drug shop as the initial response to illness, associated with increased distance from the place of residence [65, 83], This is particularly important given the high likelihood of non-adherence to NMTGs among drug shop clients.

Besides, a considerable proportion of caregivers wait more than 24 h after symptoms begin before taking the child to a hospital, largely because they have already started treatment at home [9, 25, 39]. Self-medication at home often delays access to proper medical care for children with severe malaria [65]. Self-medication for malaria has been shown to contribute to inappropriate treatment, which increases the risk of malaria drug resistance and higher malaria mortality [16].

Moreover, affordability remains a major barrier to timely malaria diagnosis and treatment in Uganda, as limited financial resources hinder access to essential health services [23, 38, 46, 84]. A study in Uganda revealed that the main reason for patients’ tendencies to incomplete treatment and save ACT for future use and sharing among family members is its high cost and the inability to always afford it [46].

CMCM addresses key barriers such as lack of affordability, limited access to quality care, high rates of self-medication, delays in seeking care, noncompliance with national malaria case management policy, and the use of fake or substandard antimalarial drugs. Providing free CMCM for all age groups, as recommended under the “24.2 Hours Initiative,” improves accessibility and reduces out-of-pocket spending on antimalarial treatment for low-income populations.

Additionally, CMCM can also contribute to mitigating the drivers of drug resistance by ensuring rational use of antimalarial drugs and strengthening early intervention strategies.

In 2010, the Ministry of Health launched the CHW programme and delivered the iCCM programme to tackle malaria, pneumonia and diarrhea among the under-five children [85]. The successful background if iCCM, makes CMCM feasible.

Positive impact of CMCM and its cost effectiveness in Uganda has been endorsed by the literature [50, 86]. Accordingly, CHWs in rural areas have played a significant role in managing the three most common illnesses including malaria among children under five years of age [10, 87, 88]. CHWs have connected remote communities to formal health care [50, 56] and reduces reliance of poorer households on lower-quality alternative providers [89]. They have contributed to increased coverage of prompt ACT treatment across many settings and are instrumental in early symptomatic detection, pre-referral treatment, and timely referral of sick children including severe malaria cases [90, 91]. Results of a study in Uganda showed that 64% of caregivers sought care from CHWs within 24 h of symptom onset [10]. Moreover, the integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) led by CHWs has shown strong potential during health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when a notable decline in outpatient department visits were experienced [86].

It should be noted that many studies have shown that the burden of malaria has shifted from younger to older individuals. This shift underscores the importance of strategic paradigm shifts from iCCM to CMCM for all age groups [92].

Literature evidence supporting governance of the initiative

The literature supports strong governance mechanism and quality assurances system of malaria case management to enhance effective coverage of malaria case management services [70].

The literature also highlights the need for comprehensive training and sensitization of health providers to improve adherence to malaria treatment policies in Uganda [34]. Capacity-building interventions, such as updated guidelines, training, mentorship, and integrated supportive supervision, have shown significant improvements in malaria case management [79, 93]. Moreover, the literature highlights that sustaining case management gains requires a reliable supply of medicines and strengthened patient education, including adherence support for ACT [80, 94].

Study limitations

There is a limited number of published articles on the drivers of malaria mortality in Uganda, particularly concerning gaps in case management for uncomplicated malaria, severe malaria, and severe malaria patients discharged from hospital. Moreover, the drivers of inadequate quality of care have not been thoroughly assessed, and positive findings are more likely to be published and thus included. Routine health-information systems in Uganda also do not capture the timeliness of treatment or the quality of care. Moreover, most available publications are small-scale studies, limiting the generalizability of their findings to the national level. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of malaria case management remains a neglected research area, with few reliable sources in the literature.