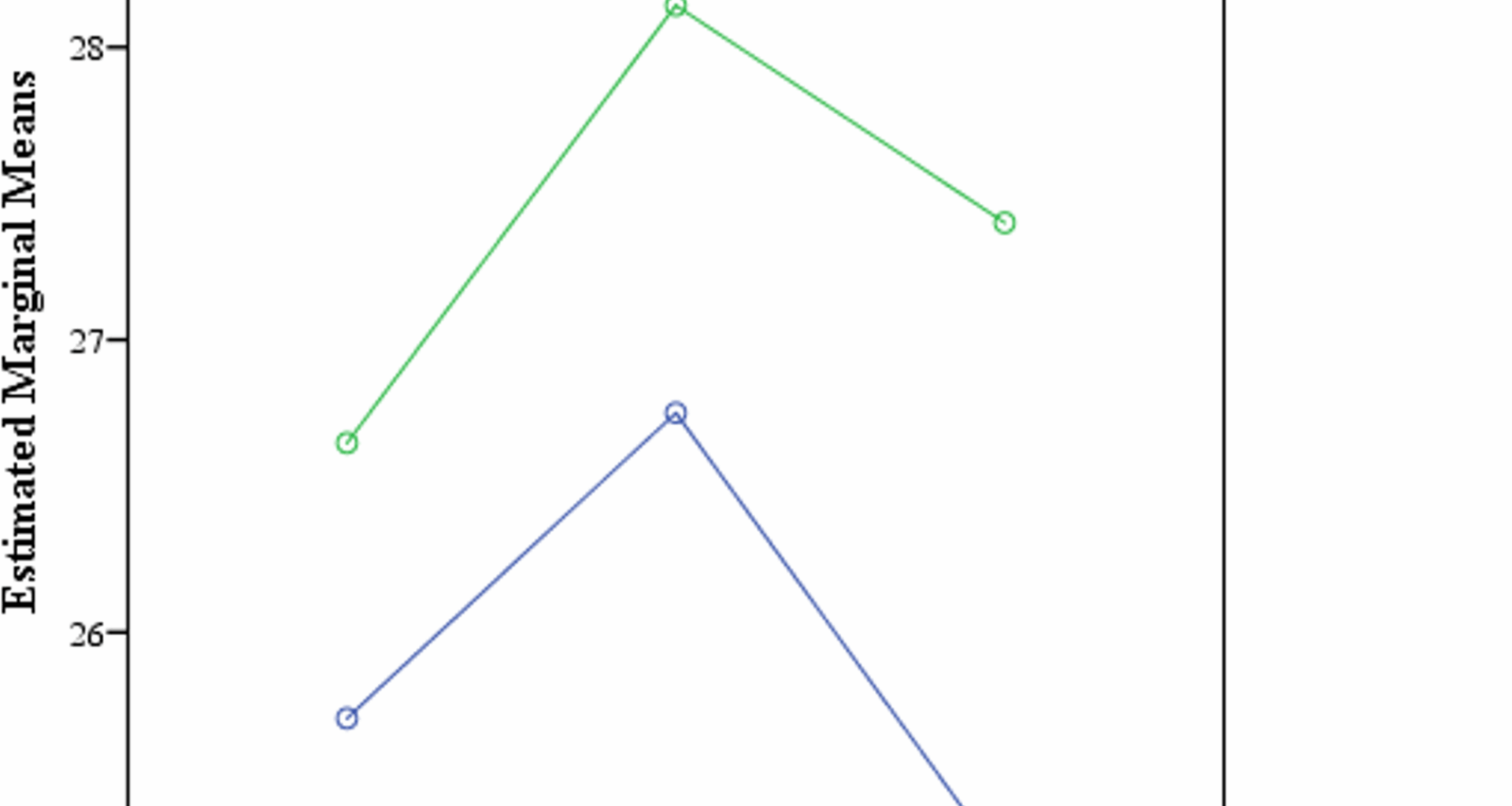

The overarching finding of the study shows a significant difference in cognitive functioning during the luteal and follicular phases of menstruation across all groups with a medium effect size (ր2p = 0.25). Based on descriptive trends and effect sizes, the largest differences were observed in the PMDD group, followed by the PMS group, compared to controls. Such findings suggest a gradient effect with PMDD affected individuals showing the most significant cognitive shifts across luteal and follicular phases of menstruation. Planned comparisons using paired samples t-test also revealed the same that the PMS and PMDD Condition performed significantly better in follicular phase of menstrual cycle on cognitive functioning. There was, however, no difference between cognitive functioning and control condition as hypothesized. These findings corroborate with those from a robust body of research indicating differences in cognitive functioning across different phases of the menstrual cycle, specifically the luteal and follicular phases, in individuals with PMS, PMDD and Controls. As evidenced in the current research, cognitive differences were more pronounced during the luteal phase; a phase which is historically associated with heightened symptomology in women with PMS and PMDD although the differences were very small in one study that assessed only working memory with a very small sample size [22]. Moreover, the subtle persistent working memory and selective attention deficits seen in women with PMS and observations of working memory deficits in PMDD participants, accompanied by challenges in concentration and irritability are consistent with the findings of the current study [18, 24]. Some authors identified the reason behind this shift in cognitive functioning to abnormalities in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in women with PMDD, a brain region important for executive functions. They also highlighted alterations in brain activity during response inhibition across menstrual phases in PMDD reinforcing the notion that hormonal changes can influence neural processes related to cognition [20]. Even so, there are inconsistent findings across the literature as evidenced in another study in which executive functioning, attention and memory were assessed along with hormonal assays in order to determine the reason behind the reduction in cognitive functioning in the luteal phase, however, no significant difference was found in these cognitive domains in luteal and follicular phase of menstrual cycle [19]. These studies were done on a very small sample size decades ago taking either only PMS group or PMDD group and some with no Control group at all [20, 26]. These methodological differences along with the fact that this is the first research of its kind in the Pakistani context can explain these discordant findings.

Within Subjects effect refers to comparison within the same group of subjects (Control with Control, PMS with PMS, and PMDD with PMDD) over different times. In the current study, it is a comparison of cognitive functioning scores over time, specifically before and after menstruation. The results show a significant change in cognitive functioning scores over time with a medium effect size (ր2p = 0.25) but the mean differences are not as inflated. A reason for this high significance value can be that the between group variation is much larger than within group variation. ANOVA looks at the ratio of between-group variability to within-group variability. Even if the mean differences are small, if the variability between groups is significantly greater than the variability within groups, ANOVA can still detect this pattern as statistically very significant. Furthermore, this finding can be explained by the effect of estrogen as there is an increase in estrogen levels after the menses finish and the follicular phase begins and estrogen has been shown to have a neuroprotective effect and can influence cognitive processes. The rise in estrogen after menstruation might explain the improvement in cognitive functioning [32]. Moreover, the physical symptoms of PMS and PMDD such as pain and bloating subside, and there might also be an emotional relief from the mood-related symptoms. This overall relief might lead to improved cognitive performance.

The Between Subjects effect refers to the comparison between different groups of subjects. In the current research, the groups are PMS, PMDD and Controls. The results suggest that when comparing the cognitive functioning across these three groups, there is no significant difference. Lastly, within subjects cognitive functioning x conditions/control examines whether the change in cognitive functioning score over time vary depending on the group (PMS, PMDD, or Control). The results indicate that there is no significant interaction. This means that the change in cognitive functioning scores over time is not different for the PMS, PMDD, and Control groups. It is challenging to detect any effect if the sample size of the study is relatively small or there is a high variability within groups, this can be the reason behind these particular findings. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of the cognitive assessment tool used (MoCA), or lack thereof, could be influencing the results. If the tool is not sensitive enough to detect subtle differences, then the groups might appear more similar in terms of cognitive functioning. MoCA is a screening tool that determines mild cognitive functioning impairments only and while it is a widely used and efficient tool for screening mild cognitive impairment, it is not specifically designed to detect subtle cognitive fluctuations that may occur across menstrual phases. This limitation may partly explain the lack of significant interaction effects observed in the present study. More sensitive neuropsychological measures, such as the n-back task for working memory, the Stroop task for attentional control and response inhibition, or computerized batteries such as CANTAB (Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery) that offer domain-specific precision, are better suited to capture subtle executive function shifts linked to hormonal variations. Future studies employing these methods, possibly alongside hormonal assays, would allow a more nuanced understanding of the cognitive changes associated with PMS and PMDD across menstrual phases. Furthermore, women with PMS or PMDD have been living with this condition most of their life and they might have developed some coping mechanisms to manage potential cognitive functioning disruptions [33]. This could have leveled the playing field, so to speak, in terms of cognitive functioning among the groups [34]. Lastly, other external factors that could not be controlled in this study like stress, lifestyle, and sleep patterns might influence cognitive functioning similarly across the groups, overshadowing potential interaction effects. Given the relatively small sample size, the standard deviations reported in Tables 1 and 2 may not fully capture the variability of cognitive performance across groups. Small samples are particularly sensitive to uniform scores or outliers, which can artificially reduce or inflate variability estimates. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution and warrant replication in larger samples.

Planned comparisons using paired samples t-test between the three conditions in luteal and follicular phases and each cognitive process separately measured revealed that all three conditions, i.e. Control, PMS and PMDD performed significantly better in follicular phase of menstrual cycle on language and on abstraction. The PMS group was unaffected in both phases of the menstrual cycle on memory. Similarly, the Control group was unaffected in both phases of the menstrual cycle on orientation. There was, however, no difference within groups in any other processes of cognition in luteal or follicular phase. These findings are inconsistent with the studies conducted previously, particularly the insignificant results of memory do not corroborate with six studies that assessed memory, working memory, attention and concentration in their research, all six showed significant differences in luteal and follicular phases in women with PMDD or PMS on memory as the only facet of cognitive functioning [15, 16, 18, 23,24,25,26]. However, there are other studies that also show no significant differences in memory before and after menstruation [19, 22]. These studies, as with the current research, had a smaller sample size which could be attributed to this lack of consistent findings. Interestingly, the PMS group performed slightly better than the control group during the luteal phase, an unexpected finding. Several factors might explain this pattern. First, sampling bias cannot be ruled out, as participants who volunteered may represent a subgroup with higher resilience or better baseline cognitive capacity. Second, motivation and effort-related differences might also account for this result; PMS participants, aware of their diagnosis, may have exerted greater effort during testing to counter perceived deficits. Similar methodological issues have been highlighted in cognitive research on PMS/PMDD and may obscure true group-level differences [25, 35]. These potential explanations warrant caution in interpreting this finding and highlight the need for replication with larger samples and more sensitive neuropsychological measures. Moreover, the absence of variability in the control group on the abstraction task during the follicular phase (SD = 0) suggests that all participants performed uniformly at this time point. This may reflect either a genuine homogeneity in cognitive functioning within the control group or a limitation of the abstraction subtest in differentiating performance in non-symptomatic populations. Consequently, these findings should be interpreted with caution, as the lack of variability restricts statistical comparisons and may indicate reduced sensitivity of this subtest in detecting subtle cognitive differences across groups. However, beyond the theoretical contributions, the present findings have practical implications for populations affected by PMS and PMDD. Cognitive fluctuations, particularly during the luteal phase, may influence academic performance (e.g., reduced working memory and attention affecting learning, test-taking, and classroom engagement) and occupational functioning (e.g., difficulties in concentration, decision-making, or sustaining focus in cognitively demanding tasks). Previous studies have suggested that women with PMS or PMDD may report greater challenges in work productivity and daily functioning during symptomatic phases, which could in part be explained by the subtle cognitive shifts observed [36]. These findings highlight the importance of considering flexible academic deadlines, workplace accommodations, and psychoeducational interventions to support women experiencing PMS/PMDD. Furthermore, awareness of these cognitive variations may encourage affected individuals to proactively adopt compensatory strategies (e.g., scheduling demanding tasks during follicular phase, using organizational aids) that mitigate the impact on performance and well-being. Moreover, a study on the cognitive functioning of women with PMS, PMDD has never been conducted in the Pakistani context before. Furthermore, language and abstraction as a facet of cognitive functioning have never been assessed in any previous studies, so the significant findings in the current research are a novel one.

Limitations

The sample size of the current study is relatively small due to attrition of participants, future studies should look into more practical ways to increase their sample size. Moreover, the sampling method was convenience sampling for recruiting pilot data set and then purposive sampling was employed to choose from this sample, both these methods are not of random selection from population making it harder to generalize the findings to the wider population. It is also important to note that women experiencing more severe PMS/PMDD symptoms or those who are more health-conscious may have been more likely to participate, while others may have been underrepresented. This overrepresentation could limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader population.

The tool used to determine PMS and PMDD was a self-report screening tool which are very sensitive to recall bias, misunderstanding, and dishonesty of responses, moreover, a screening tool cannot be used as a diagnostic tool. This study also relied on self-reported menstrual cycle timing to classify luteal and follicular phases, without hormonal or ovulation-based confirmation. Given variability in cycle length and ovulation, especially in PMS/PMDD populations, this approach may have misclassified phases, reducing internal validity and limiting causal interpretation of cognitive differences and further researches should take this into account.

Similarly, the tool used to assess cognitive functioning, MoCA, might not have utilized cognitive tasks that encompass all areas of cognitive functioning, or they might not be sensitive enough to detect subtle changes in cognitive performance. This study utilized MoCA because it was a short 10 min assessment, other cognitive tasks and tools are much longer and could not be used in the current research owing to previously mentioned attrition of sample.