A fascinating discovery in Crimea has shed new light on Neanderthal migration patterns across Eurasia. Researchers found ancient DNA in a small bone fragment that links Neanderthals from the region to those in Siberia, suggesting long-distance travel and social networks. This groundbreaking study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paints a dynamic picture of Neanderthal life, revealing their mobility and adaptability across harsh climates.

Neanderthal DNA Connects Distant Regions

In an extraordinary breakthrough, scientists have uncovered Neanderthal DNA from a tiny bone fragment found in Crimea, revealing a striking genetic link to Neanderthals from Siberia. The mitochondrial DNA extracted from the bone ties the Neanderthal to groups in the Altai region of Siberia, spanning nearly 1,900 miles. The discovery goes beyond just identifying a single individual; it paints a broader picture of Neanderthal mobility and interconnectivity across vast landscapes.

“Genetically, Star 1 is closely related to Neanderthals from the Altai via its mitochondrial DNA,” said Emily M. Pigott, lead archaeologist from the University of Vienna.

This study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that Neanderthals were not isolated, but rather engaged in long-distance interactions, moving across open landscapes and forming connections with distant groups.

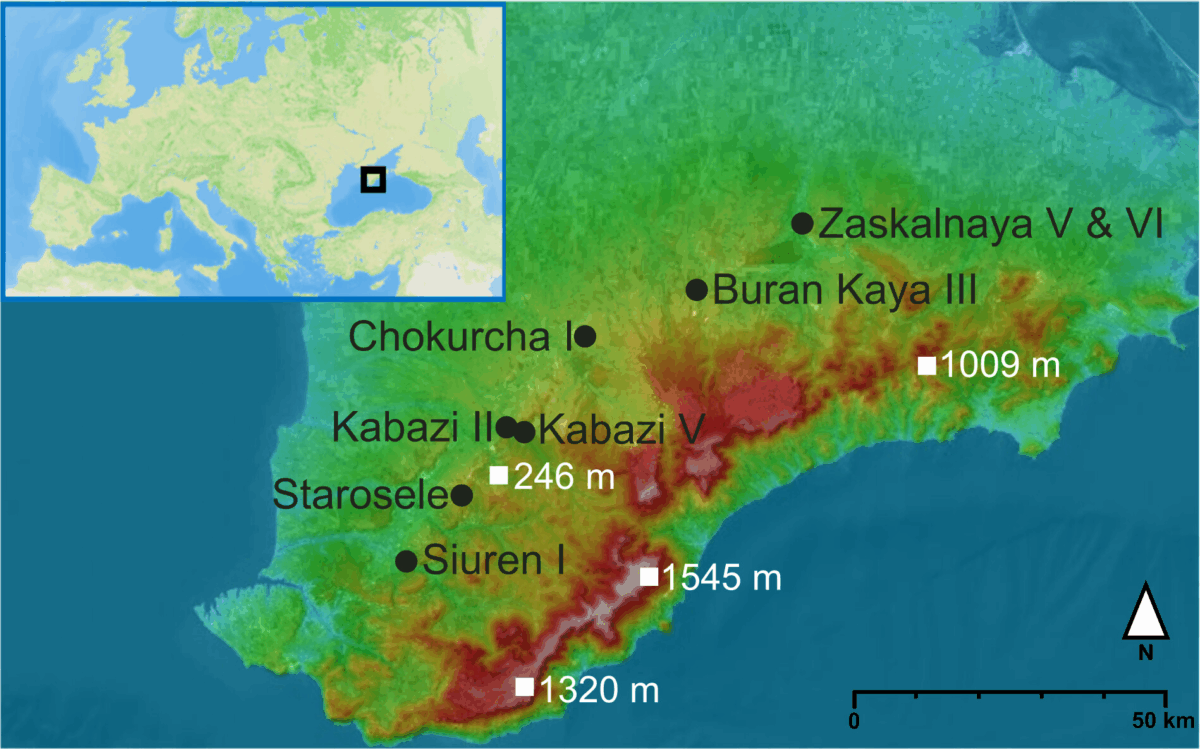

The bone, measuring just a few inches, was found at the Starosele rock shelter in Crimea, a site rich with archaeological significance. Thanks to modern biomolecular techniques like Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS), researchers were able to identify Neanderthal DNA from fragments too small to visually inspect. The research indicates that Neanderthals maintained contact over vast distances, traversing the Eurasian landmass rather than staying confined to small valleys or isolated pockets.

The Role of Climate in Neanderthal Migration

Understanding how Neanderthals could have migrated such vast distances leads researchers to consider the influence of climate on their movement. By modeling paleoclimate data, scientists have reconstructed historical climate patterns and identified open corridors between eastern Europe and Central Asia. These corridors would have been much more accessible during certain climatic conditions, with warmer, wetter periods facilitating the movement of Neanderthals across the steppes.

As the climate shifted between glacial and interglacial periods, Neanderthals likely adapted their movement patterns to follow the herds of large mammals like horses and bison, which provided both food and raw materials for their tools. This flexibility is evident in their toolkits, with the Micoquian tradition found at Starosele matching those discovered in Siberia. The presence of similar stone tools across such a broad region suggests not only physical mobility but also cultural exchange, with Neanderthals transmitting knowledge of tool-making techniques and survival strategies.

Neanderthals: A Social Network of Survival

The discovery also emphasizes the social aspect of Neanderthal life. Their ability to maintain relationships across large distances would have been essential for survival. Evidence from the Starosele site points to the exchange of not just genetic material but cultural practices as well. The Micoquian tool tradition, characterized by thin bifacial points, appears across both Crimea and Siberia, suggesting that Neanderthals shared technological knowledge over considerable distances.

This kind of social interaction hints at a complex web of communication and cooperation among Neanderthal groups. The ability to move freely across such vast expanses implies that Neanderthals were part of a larger, interconnected network, capable of surviving environmental changes by adapting their habits and strategies. The communication of ideas and techniques, such as how to craft tools or hunt in challenging climates, would have been crucial for Neanderthal success in an unpredictable world.

Neanderthal Adaptability to Changing Environments

Another key takeaway from this discovery is how Neanderthals adapted to varying environments. As the climate fluctuated between harsh winters and warmer interglacial periods, Neanderthals adjusted their behavior, shifting from open steppe environments to forested zones in search of food and materials. The archaeological record from sites like Chagyrskaya Cave in Siberia provides further evidence of Neanderthal resilience, with tools and animal remains indicating that these humans thrived in both cold, open environments and warmer, forested areas.

This adaptability was not limited to their physical surroundings but extended to their social and technological practices. Neanderthals’ ability to innovate in response to changing climates is further highlighted by the spread of Micoquian tools, which suggests the transmission of knowledge and survival skills across vast distances. It’s clear that Neanderthals were not isolated groups but rather a species capable of learning, sharing, and adapting to the world around them.

(PNAS)

A Shifting View on Neanderthal Extinction

This new research adds valuable context to the understanding of Neanderthal extinction. By the time modern humans began expanding across Europe, Neanderthals were already in decline. However, the new findings suggest that some Neanderthal populations may have persisted longer than previously thought, maintaining connections across Eurasia even as their numbers dwindled. The genetic trace found in the Crimean bone fragment provides insight into a period when Neanderthals were in contact with other human populations, offering clues about their eventual assimilation or decline.

Rather than simply vanishing, it seems that Neanderthals maintained a presence, even as new human groups arrived. The contact between these populations may have played a role in the genetic legacy that modern humans carry, with traces of Neanderthal DNA still found in many populations today. The connection between Neanderthals and modern humans is more complex and interconnected than previously assumed, suggesting that these ancient humans were not only survivors but also contributors to the genetic makeup of later generations.