The nonprofit Rewilding Europe announced its 11th project this summer in the Dauphiné Alps, a forested mountain range in southeastern France where wild horses, bison and lynx thrived more than 200 years ago.Rewilding is a restoration concept that reintroduces historically present species to a landscape with minimal other human intervention.The project is focused on fostering an environment where wild horses, alpine ibex, roe deer, vultures, Eurasian lynx and wolves can build healthy populations.The biggest challenges include working with private landowners and convincing locals that predators, such as wolves, can be beneficial.

See All Key Ideas

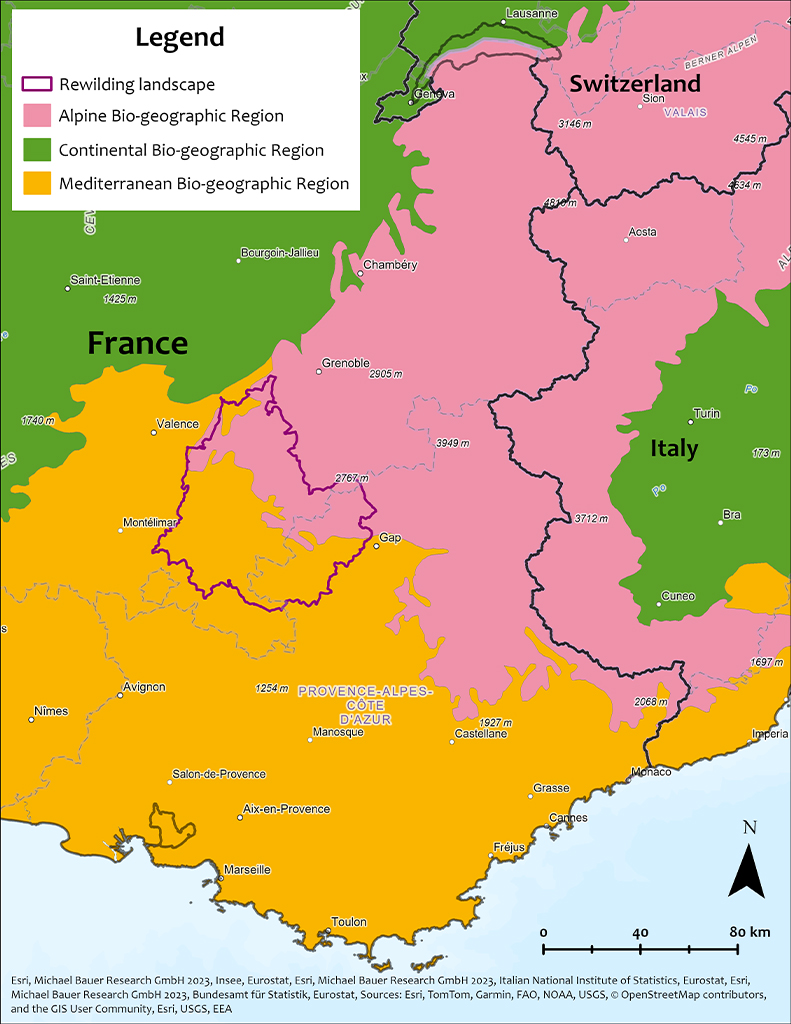

In the foothills of the western Alps in southeastern France, horned alpine ibex roam the limestone cliffs of a smaller mountain range known as the Dauphiné Alps, a region once home to thriving populations of wild horses, bison, roe deer, gray wolves, Eurasian lynx, and four species of vultures. In June of this year, the nonprofit Rewilding Europe announced the landscape as its 11th restoration site, making it France’s largest rewilding project.

The term “rewilding” emerged in the 1990s, but it’s only in the past decade that the approach has grown in popularity worldwide. Generally, rewilding is a restoration method that prioritizes conserving or reintroducing historically present species, including those wiped out locally, to boost overall biodiversity. For Rewilding Europe, this approach allows nature to flourish in a way that will make ecosystems more resilient to climate change. It also means creating economic opportunities for the people who live in these ecosystems.

“A fixed approach to nature doesn’t really work anymore,” Fabien Quétier, head of landscapes for Rewilding Europe, told Mongabay. He said rewilding is about restoring core ecosystem functions by encouraging the establishment of herbivores to maintain the forests, scavengers to mitigate disease from carcasses, and aquatic mammals like otters and beavers to maintain rivers. The project is currently focusing on ungulates such as wild horses and cattle, historical predators such as wolves and lynx, and vultures.

One of the reasons Rewilding Europe selected the French Alps for rewilding is that the region already had a head start. In the second half of the 20th century, humans started to reintroduce once-depleted species such as roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), a popular hunting species and alpine marmots (Marmota marmota), a main prey species for golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos). Over time, these species attracted the natural comeback of other animals, including keystone species — those that have an outsized role in maintaining ecosystem balance — such as the mountain goat, chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), dam-building Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber) and gray wolves (Canis lupus), an apex predator.

A wolf running through snow in the Dauphiné Alps, France. Image © Luca Melcarne.

A wolf running through snow in the Dauphiné Alps, France. Image © Luca Melcarne.

The history of human impact on the landscape goes back to the 1700s, when locals cleared much of the forests for agriculture, livestock grazing and firewood. As the Industrial Revolution kicked off in the 1800s, however, people started moving to cities, vacating the land, Quétier said. Decades of natural regeneration followed, with native tree species growing back on their own, and historical predators such as wolves making their way back over the Alps from Italy by the 1990s.

The natural comeback of the region’s wildlife signaled to locals that it was ripe for a dedicated rewilding effort. So, a group of friends decided to nominate the Dauphiné Alps as an official rewilding site in 2019 — France’s first. After a two-year feasibility study, Rewilding Europe designated a director, started raising funds, and officially launched the project earlier this year.

“It allows us to build on what’s been done already,” Olivier Raynaud, director of the subgroup Rewilding France and leader of the Dauphiné Alps project, told Mongabay. “We’re not starting from scratch.”

Roughly 60% of the Dauphiné Alps are forested, Raynaud said, and of this, nearly half are public forests. The rest is private property, meaning that for the project to succeed, Raynaud and his team need to collaborate with landowners.

One way they plan to do that is by reintroducing wild horses and cattle, such as Polish konik ponies and Scottish Galloway cows. These herbivores naturally graze the land, keeping plant growth under control, and they also disturb the soil by mixing up nutrients, breaking branches and spreading seeds that will become mature trees several years from now — without the need for humans to directly plant trees.

The Dauphiné Alps are characterized by three main vegetation zones, Quétier said: a lowland altitudinal belt with Mediterranean oaks; a montane belt with beech (genus Fagus), silver firs (Abies alba), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and black pine (Pinus nigra) that stabilize the slopes; and a subalpine belt with Norway spruce (Picea abies) and mountain pine (Pinus uncinata).

Dauphiné Alps rewilding perimeter. Image © Rewilding France.

Dauphiné Alps rewilding perimeter. Image © Rewilding France.

Among the region’s most iconic animals is the alpine ibex (Capra ibex), a wild mountain goat with long, curved horns that was hunted nearly to extinction, save for one small population in Italy. The species was brought back to the Dauphiné Alps in the late 1980s, to Vercors Regional Natural Park. It’s also considered a keystone species, along with the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), a locally endangered species that’s no longer present in the Alps but lives in the nearby Chartreuse mountain range. Rewilding France said it wants to reintroduce lynx within the next couple of years. This medium-sized wildcat is a historical predator, keeping populations of small herbivores in check without the need for hunting. That ensures the herbivores don’t wipe out all the tree species that provide good timber.

“The lynx populations in the east of France — they’re not doomed, but nobody’s very optimistic,” Raynaud said. The lynx are threatened by habitat fragmentation, vehicle collisions and genetic bottlenecks, Raynaud said. Models show that the Dauphiné Alps would be an ideal place for populations to expand. If they don’t survive in the Dauphiné Alps, their overall chances of survival in France are slim, he added.

And then there’s the other, more controversial, predator: the wolf.

The biggest challenge, said Gilles Rayé, an independent scientist who helped conduct the feasibility study, is to get humans to accept the presence of these predators. For farmers, wolves are enemies. Wolves can attack pens of livestock in packs, Rayé’s research found, which results in significant economic losses for ranchers. With more research, he said, he hopes to provide solutions that are more permanent than paying farmers compensation for killed cattle. Instead, using electric fences and guard dogs can be more effective, Rayé said.

Eurasian brown bears (Ursus arctos arctos) are another keystone species that once roamed the French Alps before they were hunted to local extinction in the 1940s. While reintroducing them would help the ecosystem, Rewilding France doesn’t plan to do so because there’s no public support for such a move, Raynaud told Mongabay.

Locals had a similar aversion to the reintroduction of four vulture species in France: the bearded (Gypaetus barbatus), griffon (Gyps fulvus), cinereous (Aegypius monachus) and Egyptian (Neophron percnopterus) vultures. All are now found across the Dauphiné Alps, thanks to dedicated captive-breeding efforts, where newborn animals are raised in captivity and later released into the wild to rebuild populations.

Vultures now serve as one of the region’s largest tourist attractions, said Gaёl Foilleret, a biologist with the nonprofit Vautours en Baronnies who isn’t directly involved with Rewilding France. Explaining to people how vultures get rid of carcasses that might otherwise contaminate rivers with bacteria and traces of lead from bullets helps people understand their value, he said. Foilleret recently founded a museum about vultures to further educate locals and visitors.

Alpine ibex in front of Mont Aiguille at sunset in the Dauphiné Alps, France. Image © Luca Melcarne.

Red deer roaring through a woodland of the Dauphiné Alps. Image © Luca Melcarne.

Griffon vulture standing in a grassland of Dauphiné Alps. Image © Luca Melcarne.

Woodland of the Dauphiné Alps. Image © Aurélien Giraud.

Roughly 60% of the Dauphiné Alps are forested. Image © Aurélien Giraud.

Wolf running across hillside in the Dauphiné Alps. Image © Luca Melcarne.

Models show that the Dauphiné Alps would be an ideal place for lynx populations to expand. Image © Aurélien Giraud.

The project involves more than just wildlife reintroductions, Quétier said. Over the next few years, they plan to restore the natural flows of channelized rivers with gravel beds and vegetation that will soak up excess water during periods of heavy rainfall, to avoid flooding in downstream towns. Meandering rivers that snake through the landscape also help direct more water absorption underground to the water table, an important source of drinking water.

Other benefits of rewilding abound, Raynaud added. Restoring the landscape protects towns from erosion. Fostering pollinators helps crops grow better. And decaying wood hosts species that prey on pests.

The economic benefits of rewilding are just as important, Raynaud and Quétier said; otherwise, it would be difficult to get locals on board. The return of popular game species opens opportunities for controlled hunting, for instance. Meanwhile, timber species offer opportunities to harvest and sell wood. The project’s first rewilding site is a 60-year conservation easement of 500 hectares (about 1,200 acres) of public forest, 25% of which is a no-extraction zone; other areas are still open to extraction. There’s also a market for wild-grown mushrooms, while recreation, such as skiing, can bring in profits for small towns.

Rewilding France plans to introduce an enterprise officer to reward private landowners for rewilding their own land and encourage other nature-centered economic opportunities, like recreation and wildlife tourism, Quétier told Mongabay.

Still, Raynaud said, the project is somewhat of an experiment.

“It’s very hard to place a bet on what’s going to be working in the next 50 years,” he said. Local temperatures are projected to increase by 4° Celsius (7.2° Fahrenheit) by 2050 compared with 2.5°C (4.5°F) for the rest of France, he added, meaning vegetation and animals are expected to shift northward — and to higher altitudes — by several hundred meters.

“We can either expect the forests in this place to collapse, or we can reestablish herbivory so that we give the forest a chance to evolve and increase its resilience before these major changes arise,” Raynaud said.

Even here, in this remote swath of rural land, the effects of climate change are clear: longer droughts, more frequent heat waves, forest fires, and rivers that stop flowing by the end of summer.

“All of these things are happening for the first time, or more frequently, more intensively, than before,” Quétier said. “People are looking for new ideas on how to deal with that, and rewilding is one of those ideas.”

Banner image: Two male ibex in front of Mont Aiguille in the Dauphiné Alps, France. Image © Luca Melcarne.