December 15 marks 50 years since newly elected prime minister Robert Muldoon cancelled a contributory superannuation scheme, and imposed the growing costs of the pension onto struggling taxpayers. Described as the ‘worst decision by a New Zealand politician, ever’, the consequences of Muldoon’s actions still reverberate. Eric Frykberg looks at whether a scheme like the one Muldoon killed off can be revived, and proposes options for making it affordable. Is it too late to salvage New Zealand’s future?

This feature was made with the support of the Auckland Radio Trust, sponsors of the Vince Geddes In-Depth Journalism Fund.

Chloe is planning to move overseas. The 19-year-old journalism student at Massey is pessimistic about her future in New Zealand. “We won’t have the funds to own a house, let alone help the environment,” she says.

“Everything is kind of going down the drain, and everyone’s leaving because of that. At the moment, we can barely afford to have our own savings, let alone help fund climate change, so we are leaving because there is nothing here for us.”

Chloe thinks seeking employment overseas will be an inevitable pathway for her, a philosophy shared by her fellow student, Anna, aged 20.

“I doubt that I’ll have money for a house in the future,” Anna says, “and I have no trust in the government having money for anything else if we ourselves don’t have anything.”

A third student, 19-year-old Eliza, studies spatial design and is a bit more confident, but not by much. “I’m not sure how much confidence I have in the government’s ability to help our generation. I think they are more focused on the past or the current, not so much into the future.”

One reason for this negativity is that governments in New Zealand have a way of repeatedly living beyond their means. The current government consumes about one third of the economy, but has to Buy Now, Pay Later to honour its bills. The “pay” part of that equation comes to more than $10 billion of borrowed money a year.

And that borrowing still does not bring in enough money to pay for the state’s real obligations. The full costs of maintaining infrastructure are often omitted from annual government budgets. And state spending generally falls short of meeting social goals as well. For instance, the Jobseeker benefit can be as little as one third of the living wage. Meanwhile, accumulated debt rises, bit by bit.

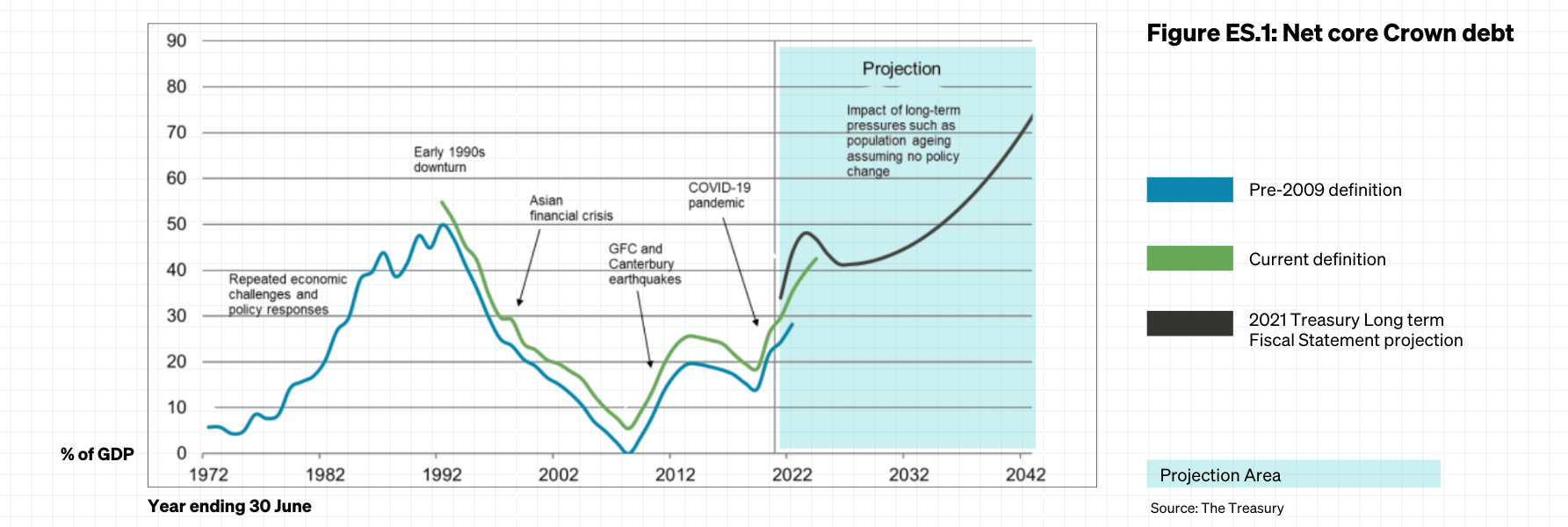

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

This graph portrays a sort of zig zag economics, with public debt rising from a low at the end of the Holyoake era to a high of 50% of GDP during Sir Robert Muldoon’s ruthless administration and Sir Roger Douglas’s costly correction. Two subsequent finance ministers, Sir Bill Birch and Sir Michael Cullen, meticulously counted every penny, and brought state debt down to a negligible 5.4% of GDP. The debt then rose again during the Global Financial Crisis, fell in its aftermath, and rose again to pay for Covid as well as the Ardern/Hipkins government’s political ambitions.

At first sight, its make sense to borrow money during hard times and pay it back when times are good, like a household that borrows money to fix a leaking roof and keeps its costs down in the subsequent months. According to this argument, zig zag economics can keep New Zealand going indefinitely into the future, with no need to pre-fund for future crises.

The trouble is, the debt graph has become asymmetrical, and the zig zag is veering off course. The debt troughs are not falling as low as they used to, and the debt peaks are getting higher. “New Zealand has seen debt rising in recent decades, partly because responses to adverse shocks have not been matched by savings,” Treasury wrote in its Te Ara Mokopuna report in August. “New Zealand is likely to experience further shocks in the future, and we now have less capacity to respond because debt is higher.”

Te Ara Mokopuna produced a table showing just how expensive natural disasters can be.

The table shows the most costly disasters were the $66bn Covid pandemic and the $23bn Canterbury earthquakes. While the $66bn Covid bill turned out later to have been diluted by unrelated government spending, the collective costs of paying for crises in the past still carry a warning for crises of the future, which will almost certainly be worse.

And more is at risk than public finances. People’s private assets are in the firing line too. Another report (“Building Resilience to Hazards – Long Term Insights Briefing”) done by an expert panel set up by the Ministry for the Environment found climate change has the power to extinguish the value of people’s overpriced and hard-earned homes, due to uninsurable flood risks. The report supported the grim picture of thousands of people being trapped for a lifetime in dangerous, decaying houses, in flood-prone regions.

They would be unable to buy a new house in a safe location because no one else would buy their old property and provide the money to move on. Nor would insurance be always available, nor a mortgage. Wealthy people could afford to pay their way out, or would not be living in a risky zone in the first place. But low-income people could be stuck in a house that progressively decays with each new flood and each cycle of deferred maintenance.

The report estimated $4.1bn in household assets could face serious harm over the next 30 years.

A few weeks later, a second report was even more alarming. Done by Earth Sciences New Zealand, it found 750,000 people live in areas vulnerable to a one-in-100-years flood, and the value of their at-risk assets was a whopping $235bn.

The environment ministry panel was emphatic: It warned against any hope of a fairy godmother stepping in. The owners of these houses would essentially be on their own. “Central government is not liable for these losses, but faces growing public expectation to cover them, given New Zealand’s recent history of ad-hoc buyouts,” the panel wrote. “The value of the property in a high-risk area might gradually decrease over time, meaning that the losses are gradually borne by successive owners,” the report declared.

“There is an enduring role for central government to support people to potentially move on, but they should not expect buyouts.”

Any doubts about how serious the problem is would have been dispelled by a report from the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) in August. Its Long-Term Insights Briefing (LTIB) described twin threats: less money coming in to future governments and more money going back out.

For example, the gig economy, the displacement of workers by AI and global transactions by digital companies could reduce the total quantum of taxes paid to the state. Climate change could have the same effect, if it undermined the productive capacity of blocks of land. Paradoxically, fighting climate change could be costly too, if it required lower levels of agricultural production to reduce emissions.

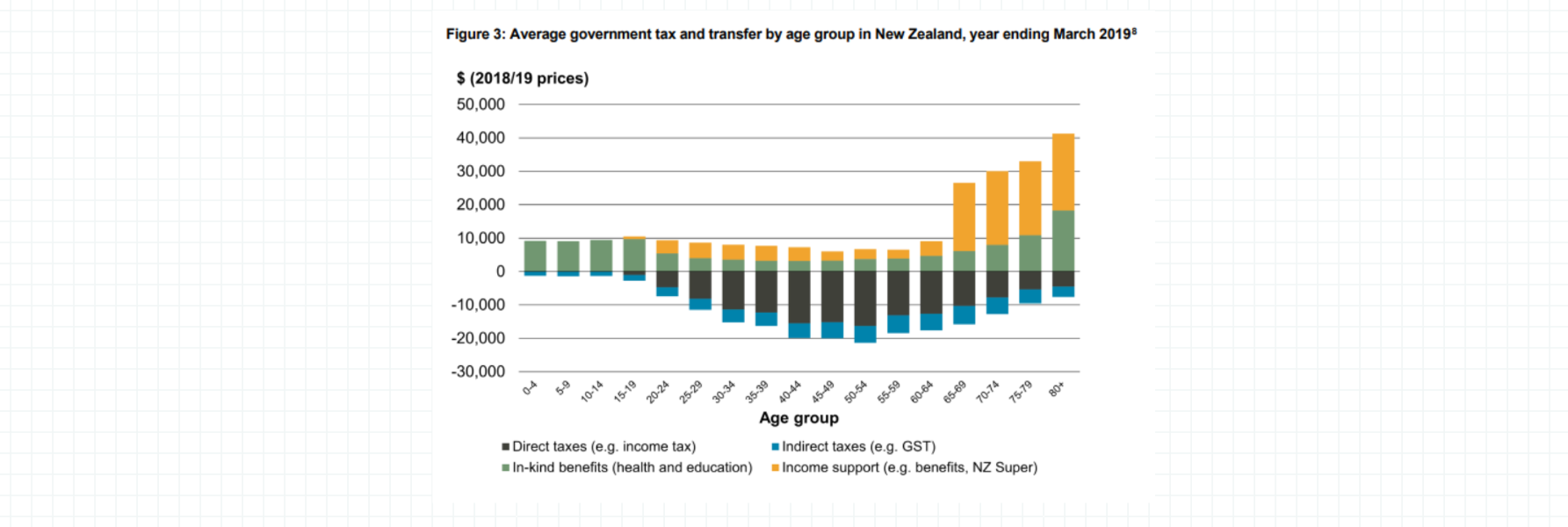

Along with less money coming in, there would be more money going out, according to the IRD report. The net cost of the pension would rise to 7.5% of GDP in 2080 based on current settings. In addition, healthcare costs, which generally rise faster than overall inflation, would be even worse, because a bigger share of hospital patients would be elderly.

The IRD made some suggestions about fixing these problems; a smarter tax system, getting more people into work, making them work longer, raising the age of superannuation and other options. It did not presume to tell the government which one of these choices should be taken. But it concluded by saying “fiscal sustainability is an important issue for our tax system”, which is IRD-speak for: Wellington, we have a problem.

The age-old problem

Even if New Zealand is spared disasters caused by climate change, it will still face a long list of other unfunded liabilities, such as the public pension. This is budgeted at $24.7bn in the current financial year, making it the second costliest item on the menu, and is predicted to double in the coming years as New Zealand population ages.

In a speech last September, Treasury’s chief economic adviser, Dominick Stephens, warned that New Zealand fiscal policies are not sustainable in the long run. “There is no silver bullet… governments will likely need to draw on multiple expenditure and revenue changes to close the fiscal gap.”

The bars below the zero level reveal the declining income from the elderly to the state. The bars above the line show the increasing payments to the elderly by the state.

“The Treasury has been banging the drum for many years on the long-term unsustainability of fiscal policy,” Stephens said.

“The fact that we are living longer lives is a great thing. Treasury has repeatedly pointed out that, as lives lengthen, current policies will become unaffordable. What that really means is that fiscal policy, and society more generally, is going to have to adapt.”

A more recent report by Treasury, He Tirohanga Mokopuna, was even more dramatic. It forecast state spending per person to double by 2065. Without a change in policy, this would push state debt to 200% of GDP, five times the current level. Alternatively, the cost could be met by increasing income tax by 50% or doubling GST.)

Muldoon’s wreckage and what could have been

Fifty years ago, Sir Robert Muldoon killed off a scheme introduced by the third Labour government which was intended to solve this problem. People would have been required to pay into a state-run superannuation project which would buy them a pension at the end of their working lives. Muldoon fought this idea during the 1975 election and characterised it as a “communist takeover”, fortified by the notorious Dancing Cossacks TV ad. The inconvenient fact that the Cossacks fought for the Whites against the Russian Bolsheviks was ignored by the electorate, which voted Muldoon into office. A few weeks later, he cancelled the scheme by edict.

Robert Muldoon in 1982 (Photo by Rob Taggart/Central Press/Getty Images)

Robert Muldoon in 1982 (Photo by Rob Taggart/Central Press/Getty Images)

A subsequent court case found Muldoon’s decree was ultra vires, so his stop-payment order was ruled to be illegal. The court reasoned that Muldoon was not entitled to cancel an act of parliament by executive order, due to a longstanding constitutional convention. However, subsequent legislation abolished the scheme anyway. People got a few hundred dollars in refunds, and an unsustainable pension system was imposed on the public.

In 2007, Brian Gaynor wrote that the scheme could have made New Zealand the “Switzerland of the South Pacific”. He estimated that its investment portfolio would have reached $240 billion, had it been allowed to continue. This assessment was based on an annual contribution of 8% per employee and prevailing average returns on government bonds and the New Zealand share market.

Subsequent analysis shows the value of the scheme would have grown exponentially in the years since Gaynor wrote those words. A parallel body, the NZ Super Fund (NZSF), has grown from $14bn to $86bn in that time. If Muldoon’s victim had shown a similar growth rate, it would have been worth more than $1tn by now.

Of course, other matters could have changed this outcome. The scheme was devised in a different era, and it would not have had the investment freedom that the NZSF did. But even if it made only the global average for sovereign wealth funds, instead of breaking records like the NZSF, it would have given New Zealand some help in dealing with the giant economic pothole in the road ahead, which everyone knows about but no one can agree on how to avoid.

Introducing sovereign wealth funds

So, 50 years later, is it too late to turn this around? Perhaps not.

Perhaps New Zealanders have blundered into an unfixable mess, and must accept that fact and muddle through. Or perhaps things can improve, and governments could decide that today’s voters are no more important than their children or grandchildren. Perhaps they could spend less and save more, like a thrifty child. Perhaps they could earn $100, spend $90 and put aside $10 for a rainy day, or rather a storm-ravaged downpour.

Plenty of countries already do this. Norway has a spectacular SWF, currently worth the equivalent of $NZ3.3 trillion. Singapore has a famous scheme worth $NZ565bn. Middle Eastern countries that rely on a single, non-renewable resource like oil, mostly have such a fund. The philosophy behind these schemes is simple. Only a fool spends all his money on payday. A wise person puts some aside. And if it is good enough for individuals, it is good enough for governments.

New Zealand has already made a tentative start in this direction. It established the NZ Super Fund in 2003 to help pay the future costs of the state pension. This has been a big success. World-beating investment methods pushed its value up to $89bn. While that large sum will still pay only about one fifth of peak pension costs, it is generally recognised as a good beginning. So why not set up a similar fund, to pay for floods, droughts or pandemics?

Sovereign wealth funds are big internationally. They are overseen by the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, (IFSWF), whose 37 members have almost $US9 trillion dollars in investments and added $US72.1bn to their portfolio last year alone. Apart from Norway, the biggest are in China or the Middle East. As well as national schemes such as the NZSF, there are several programmes that operate sub-nationally or are aimed to help a particular sector or set of sectors within an economy. But all are built on the principle of save-now-pay-later.

The appeal of SWFs persists. The United States is the latest country to take a look. Donald Trump signed an executive order earlier this year calling for the establishment of such a fund “to promote fiscal sustainability, lessen the burden of taxes on American families and small businesses, establish long-term economic security, and promote U.S. economic and strategic leadership internationally.” The Trump order said the Federal Government had $US5.7 trillion in assets, which could provide the basis of such a fund. It remains to be seen whether this proposal will survive the current tumult in Washington.

Here in New Zealand, there are mixed opinions from experts and politicians alike on whether New Zealand should join in this practice.

Simplicity’s chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub is absolutely in favour of more long-term savings. He says the NZSF has done an extraordinary job, though it is still not big enough. But instead of adding a new SWF to the list, he proposes paying more money into the NZSF, to increase its capacity. The NZSF could also broaden its scope and be made more sustainable via means testing. Eaqub also thinks New Zealand needs more private savings, and he supports a capital gains tax, which has been better tested internationally than a wealth tax. However, neither would be a game changer.

Simplicity chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub

Simplicity chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub

“The bigger issue is whether or not we’ve got the fundamental settings right, so that the habit of regular savings and the power of compounding returns make the pension system and the fiscal system more sustainable over time,” he says. “But the idea of having a sovereign wealth fund that saves now for later is a good one, because we’ve known for some time about the problems of an ageing population and an unsustainable tax system.”

Eaqub’s views are broadly supported by Council of Trade Unions (CTU) economist Craig Renney, who cites the coming costs of health, climate change, employment and other challenges as reasons for pressing ahead. “We’ve created a fund (NZSF) to help manage our superannuation liabilities going forward and that’s great,” Renney says. “It’s not enough, but it’s great. But we’ve also got other challenges and so if we can deliver patient capital now to help reduce and defray the costs of these challenges in future, that’s something that we should absolutely be doing.”

Renney adds a future fund could solve another problem simultaneously – a chronic shortage of money for long-term investment which currently gives New Zealand a so-called “shallow capital” problem. “As a country, we have a real difficulty in getting capital for investments, particularly domestically generated capital, and a future fund may help to address that problem and match up our investment need with available finance.”

Not everyone, though, supports more or bigger SWFs. Business New Zealand’s chief economist John Pask, is not a fan. He says there are other ways of protecting the future besides setting up such funds, like paying down state debt to make it easier to borrow money later. Pask adds New Zealand also needs to think very carefully about how governments spend their citizens’ money on their behalf instead of letting them keep their money to make their own choices.

Pask cites another risk: politicians might have noble goals when they set up a future fund, but their successors in coming years might forget or ignore the original purpose of the scheme. They might dip into these funds for political reasons, or fail to sustain them because it is cheaper and easier to pursue a policy of passive neglect. “I’m not totally opposed to the concept of more sovereign wealth funds, but they would have to be fleshed out very carefully in terms of their governance.”

Where the parties stand

Political parties are split on the matter. The Green Party supports a future fund as an idea worth exploring, due to the growing costs of climate change, and it accuses the current government of going backwards on it. “The longer we delay, the longer we leave communities in the dark, fending for themselves,” says the party’s economic development spokesperson, Julie Anne Genter. “What is clear is that our country desperately needs an enduring approach when it comes to funding climate action and preparing for climate change.”

The Act Party wants debt paid down before investing more in sovereign funds. It sees SWFs as a leveraged bet on the stock market using taxpayer money. By contrast, paying down debt would deliver a guaranteed return. The party adds that New Zealand had low levels of public debt at the time of both the Christchurch earthquakes and Global Financial Crisis, which made it easier to borrow money to help the victims of these events. But, says Act, it would be much harder to do the same thing now because state debts are so much higher.

New Zealand First wants strong action to protect New Zealand’s future. In September, Winston Peters called for Kiwisaver to be made compulsory, raised to 8%, then 10%, and offset by tax cuts. “We are going to turn Kiwisaver into a serious New Zealand asset-owning entity,” he said. Further details on this idea are due later. Meanwhile, a public fund to invest in infrastructure, which would ultimately be worth $100bn has been suggested by Shane Jones and is almost certain to be put before voters at the next election.

The National-led government was briefed by Treasury last year on setting up a massive holding company that would own state assets such as Kiwibank, KiwiRail and Transpower. It would run them with a commercial focus to assist state finances by making good profits. Ministers at the time insisted there was no official policy on this and they had an open mind on what to do next. They have repeatedly said they want to ensure state assets deliver value to the taxpayers that own them, and say robust policies will be taken to the next election.

The Labour Party prevaricated for many months on this matter, before finally outlining a future fund of its own, which it will put to voters at the next election. This would be based on a $200m injection from a future government’s available budget and would be augmented by the assets of selected state enterprises. The fund would be required to invest in New Zealand assets, not overseas shares, in order to stimulate the economy domestically. The policy would operate in tandem with a limited capital gains tax. In launching Labour’s future fund, leader Chris Hipkins admitted his scheme would accumulate less wealth than would be achieved by an international fund, but said it would produce more well-paid jobs.

Te Pāti Māori did not respond to emailed requests for comment. But its last election manifesto declared that wealthy people should pay far more tax. There would be higher income tax for well-paid people, a wealth tax for people with fixed assets, higher corporate tax, a land banking tax and a vacant property tax. But the income raised from this appeared to be aimed at fixing the social problems of the present, rather than saving for the future.

Who’s paying for this?

The problem for all these political parties is that setting up a new sovereign wealth fund would be very expensive. After all, governments these days are so fiscally stressed that they can hardly afford to stand still, let alone save money for the future. But, there are options. They mainly involve shifting tax burdens, putting an impost on currently untaxed transactions or manoeuvring state assets to make greater use of them.

Capital gains tax: This tax would get revenue from rising asset values, such as real estate, which often give little money to the state at present. While house prices have dipped in the last three years, the value of New Zealand’s housing stock has risen from $138bn 30 years ago to $1.64 trillion today, according to the Reserve Bank. People owning several of those houses could make more money from capital gain than from their day job during property spikes, especially if they used geared, or leveraged, investment techniques. Yet they would sometimes pay less tax than a Monday to Friday worker.

A significant capital gains tax has been killed off for political reasons by both major parties. After all, why alienate middle class voters who own about a third of New Zealand’s housing stock as investments, and could vote either Labour or National, depending on how they are feeling on polling day?

Labour finance spokesperson Barbara Edmonds and leader Chris Hipkins launch the Future Fund in Auckland (Photo: Dean Purcell/New Zealand Herald via Getty Images)

A broad-based capital gains tax won majority recommendation in 2019’s landmark report by the Tax Working Group, chaired by the former finance minister Sir Michael Cullen. This report estimated such a tax would raise 1.2% of GDP on average, over time. The recent dip in house prices would have reduced that income, but New Zealand’s GDP is approximately $430 billion, so a capital gains tax over time would bring in $5.16 billion annually.

While that still falls far short of recent government deficits, it is approximately double the average sum paid by governments into the NZSF each year. Income from a CGT would not have to be tied to a future fund – hypothecated in technical terms – but it could still be used to offset its cost in the total pool of state money.

Wealth tax: This idea was pushed by former finance minister Grant Robertson and his revenue minister David Parker during the last years of the sixth Labour government. It was then cancelled by prime minister Chris Hipkins. It would have made people pay 1% of their assets above a threshold of $5m per person. The family home and assets such as cars and boats would be exempt. According to a Treasury document, 46,000 people would have been liable to pay this tax, and the income from this scheme would have been approximately $2.7bn annually one year after its implementation.

Parker and Robertson intended to use this money to ease the tax burden on low-income people – the much-discussed “tax switch” – but its revenue could easily be directed at long-term funding, and would match the contributions made by governments over the years to the NZSF.

Wealth taxes have been falling out of favour internationally, even among Scandinavia’s famous smiling socialists. One reason was the high cost of implementation. They could also make life hard for people with poor-performing assets. But they would also be progressive, since rich people tend to have their wealth in assets rather than income. The French economist Thomas Pikkety called for a global property tax, declaring that in the modern era “wealth is so concentrated that a large segment of society is virtually unaware of its existence”.

The Singapore model: Under this scheme, governments could get rich using their own property as investment tools. The idea is that state assets could be isolated in standalone entities which would then invest for the future, in a manner similar to the NZSF. For New Zealand, a scheme like this would focus on the three big electricity companies, Meridian, Genesis and Mercury, which are 51% owned by the state.

The dividends from the state share of these firms would be used to finance further investments. The capital base of each company could also be used to leverage buy-ins of New Zealand or foreign corporations, depending on how high the companies’ debts are relative to income streams at any particular time.

This idea was flirted with by Labour back when it was led by David Cunliffe and David Parker in 2014, but it died when National won the subsequent election. The current government is looking at a similar idea from Treasury, but there are no promises.

The Singapore model – Temasek – began with state assets such as Singapore Airlines which were leveraged to create a massive global share portfolio, with investments in companies such as Amazon and Ali Baba.

Selling the family silver to the family: This idea would have public assets sold to a New Zealand-owned company which would invest in local infrastructure and other needs. Items for sale would include the government’s stake in mixed ownership electricity companies, toll roads, local government assets and even management contracts for schools and hospitals. The buyers of these assets would be the only large source of domestic capital in New Zealand, Kiwisaver funds, which are currently worth about $123 billion.

One Kiwisaver funder, Sam Stubbs of Simplicity, is a strong proponent of this sort of thinking and has gone some way towards putting his money where his mouth is. Stubbs thinks Kiwisaver managers are increasingly investing their money offshore, which might bring good dividends but does not create jobs at home, and does little for GDP growth. But he says building infrastructure creates jobs and in the long run builds a far stronger economy than simply getting a dividend cheque from abroad. To push this idea further, Simplicity recently announced a new company, InfraKiwi, which would list on the stock exchange and provide funds for infrastructure such as roads and power lines.

Stubbs believes running state assets with a commercial focus would make sense. He cites the water leakages in Wellington that linger on, compared with the electricity wires in the capital, which are repaired promptly because their owner wants people to keep on paying their power bills. So, his idea would have state assets administered more efficiently. And while his scheme might not produce a large pile of cash, like a conventional SWF, he says it would produce a stronger economy and achieve inter-generational fairness via a different means.

Deferred land tax: Under this scheme – researched by Oxford economist John Muellbauer – property owners would incur a small capital charge on their home each year. But they would not have to actually pay the money until they die or the house is sold. This amounts to a kind of shared equity scheme between the home owner and the state. New Zealand’s residential real estate is worth approximately $1.6 trillion, of which about half is in the value of the land. A 0.50% deferred land tax would bring in $4 billion a year, which is comparable to a capital gains tax. But people would not be required to make actual payments of money each month.

In an article written for the OECD, Muellbauer argued strongly for a deferred land tax, adding it could be adjusted for green values. This would be achieved by putting a fee on the house as well as the land and reducing the house levy at a rate proportional to the building’s energy efficiency. Muellbauer argued such a tax would be difficult to avoid, would incentivise climate-friendly building and would broaden the state’s revenue base.

In the meantime, not saving for the future with a vague idea of somehow doing better is the default position for most New Zealand politicians. In addition, loose or sloppy state spending, with or without an SWF, can make things worse. This issue was addressed in a recent suggestion by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which would inhibit governments from making a bad situation worse.

Under this proposal, New Zealand would acquire a new, independent, institution to scrutinise all government policies and verify their fiscal sustainability. This would strengthen New Zealand’s financial oversight by establishing a special watchdog which would report to parliament, not the government. It would help parliament hold governments to account for their fiscal strategies. A similar body exists in the United States – the Congressional Budget Office – which has issued trenchant commentary on events like the Trump administration’s tax cuts.

In New Zealand, Treasury already undertakes independent analysis of government actions, but a parliamentary oversight body could provide even more scrutiny.

Finally, some commentators find fault with the entire principle of more or bigger sovereign wealth funds. They base their argument on two concepts beloved by economists: perverse incentives and unintended consequences. According to these concerns, setting up SWFs could lead people to neglect taking care of themselves because they think the government will do it for them. This would reduce society’s overall resilience to adverse events and could increase the cost of future shocks to governments.

Perhaps things can improve, and governments could decide that today’s voters are no more important than their children or grandchildren.

This trend could prove costly for ordinary people. They might have neglected providing adequate protection via insurance, because they trust an SWF to pay the bill for them. But an SWF might face serious economic constraints that reduce its ability to help the victims of a crisis. Ordinary citizens might not be aware of this deficiency til too late, leaving everyone facing an insoluble problem.

In seeking to avert unintended consequences and perverse outcomes, the Te Ara Mokopuna authors urge governments to state clearly in advance what they can and can’t do during a crisis. This would make clear what steps citizens need to take to protect themselves and what they can expect from the government. It would spread responsibility rationally and make costly overlaps less likely. People would not be paying twice for the same service but there would also be fewer gaps in society’s defences, which would save individuals and communities from potentially catastrophic losses.

President Joe Biden once remarked about politics, “One role of government is to go where venture capital won’t.” The natural disasters facing New Zealand in future are an area where venture capital probably won’t go, except with restrictive caveats and expensive premiums. This means future funding by governments may prove New Zealand’s only option, whether it is seen as politically desirable or not.