A major new report into the future of the energy system says New Zealand must learn to do more with less gas.

Energy To Grow, from Big Three consultancy group Boston Consulting Group and commissioned by the four gentailers, is the successor to the 2022 Future is Electric report by the same firm. The earlier report proved to be massively influential for the power market, laying out scenarios about the build-out of renewables, the transition away from fossil fuels and increased demand from the electrification of transport and industry.

Richard Hobbs, a partner at BCG and the author of both reports, told Newsroom that New Zealand had largely proceeded along the pathway recommended by the 2022 document. The two big focuses of that report were the importance of building more renewable energy and moving to a smarter system, with more demand response and distributed generation like rooftop solar.

“So, what have we seen since then? In the last three years, we’ve had the equivalent of 7 percent of our existing supply has come online in terms of new renewable generation. There is another 10 percent already under construction that will come online by 2027,” he said.

“That will increase New Zealand’s renewable electricity percentage to about 95 percent at that time, which will be right up there with the highest in the world. At the same time, a lot of the smart system measures have been implemented.”

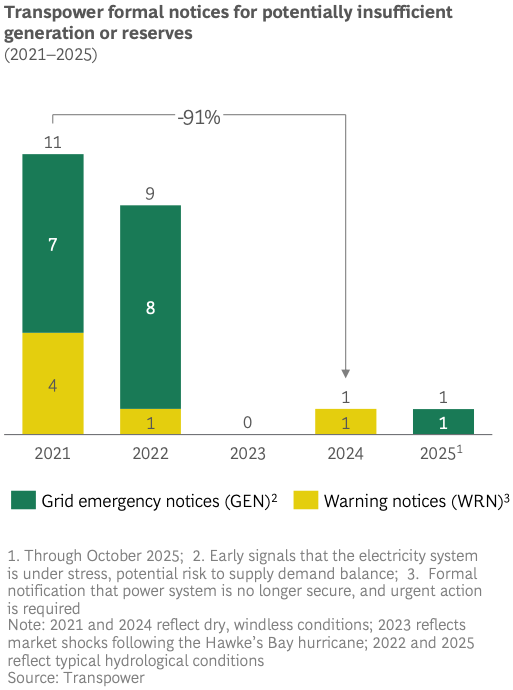

As evidence of the latter, Hobbs pointed to the steep decline in how often Transpower issues notices about insufficient generation. In 2021, 11 notices were issued. Last year, only one was.

So New Zealand is doing well – why the need for another report?

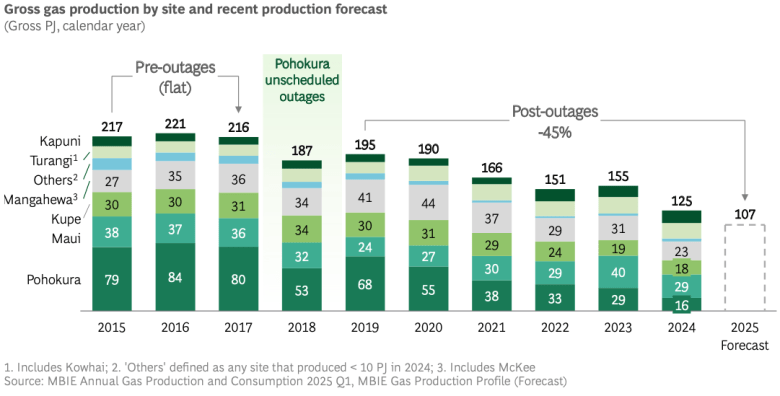

“Really, the main story of what’s happened in the last three years is just the bottom has fallen out of the gas market. We’ve seen gas supply decline 45 percent in the last six years – dramatically below what anyone was forecasting,” he said.

“That context, overlaid with a dry year in 2024, really exposed quite a few fragilities in our energy system.”

In the new report, Hobbs lays out recommendations for how the energy system – including generators, gas developers, industrial users and regulators – should respond in the next five to 10 years to get back on track.

That involves using our remaining gas reserves more thoughtfully, helping those who can switch away from gas, turning to the most efficient and immediate sources of new gas (hint: not offshore exploration) and continuing the rapid construction of new renewables to free up gas for other uses and bring down power prices.

Gas isn’t coming back

While the report spends a considerable amount of time examining how to develop more gas, Hobbs is clear that this isn’t about returning to the heyday of the fossil fuel in the 2000s.

“When BCG talks about arresting the rapid rate of decline in gas supply, we are absolutely not envisaging some kind of gas renaissance where supply starts increasing again,” he said.

In 2015, New Zealand produced 217 petajoules of gas. That number was relatively flat at the time – 221 PJ the next year, 216 the year after that.

Since then, however, supply has declined precipitously. In 2024, just 125 PJ was produced and Hobbs estimates this year’s total will be around 107 PJ – half of what it was a decade ago.

By 2030, the industry forecasts production will be around 63 PJ. But the industry’s forecasts have repeatedly been too high, with 2024 totals landing 10 percent below the producers’ own predictions. BCG’s report puts the figure at somewhere between 50 PJ (in a managed scenario) and 36 PJ (the worst case).

The difference between the two BCG scenarios is significant, the equivalent of all the gas used by commercial and residential consumers in 2024. That is the focus of BCG’s recommended actions – not boosting gas production to 200 PJ, Hobbs said, but slowing the decline so gas is still available.

Doing that requires actions on both the supply and demand side. On supply, targeting existing fields for additional development could help extend their lives and has a better chance of succeeding (and doing so quickly) than looking for brand-new reserves.

That’s easier said than done. More than $1.5 billion has spent drilling 53 wells in existing fields since 2020, with little to show for it. Onshore fields, however, have proved more successful than offshore. The Tūrangi gas field is producing more than 50 percent more gas in 2025 than it did in 2019, Kapuni has seen a slight increase as well and the onshore Mangahewa field has slowed its rate of decline.

Offshore fields, however, are fading fast – the Māui field could be shut down in two years’ time, while the Pohokura gas field is behind 85 percent of the recent decline in production.

In order to achieve the “managed transition” target, new development needs to continue succeeding in Tūrangi, Mangahewa and at least one more of the remaining four fields.

Another lever to pull is gas storage. Currently, the country’s only gas storage facility is in the old Ahuroa field – but its capacity was downgraded from 18 PJ to just 6-8 PJ due to water ingress. Currently, the market can rely on Methanex to scale down its usage at times of high demand or low supply, freeing up gas – but BCG believes it will be uneconomic for Methanex to continue operating by the end of the decade.

With Methanex gone, an investment in new storage capacity could help smooth access to gas, if the production side of things is also addressed.

LNG ‘if our arm is twisted’

There is also the prospect of importing LNG (which the Government is keen on), but Hobbs said this is a last resort.

“Our starting position is it is preferable to have a well-functioning domestic gas market than having LNG,” he said. “It does cost a lot and you don’t really want to have to go there with LNG, to be honest. But if you have to – if you just simply are going to run out of gas and it is going to lead to widespread deindustrialisation, you kind of need to go there.”

That said, the report recommends the Government take “least regret” actions – undertaking a business case and potentially arranging consents – in the event LNG imports are needed. The cost of a facility, which could approach $1 billion, should be levied across the entire gas and power sector to socialise the cost, BCG advised.

“If our arm is twisted into needing to use LNG, then we will need to use it, but we should be pulling all the other available levers, including on the demand side first, to try to fix that situation,” Hobbs said.

That brings up the other set of options to address the gas shortage – reducing the usage. Methanex, as noted, could close down in the coming years. So too for the Ballance Agri-Nutrients urea plant, which like Methanex produces just a few dollars of GDP per gigajoule of gas consumed. Gas also makes up 75 to 85 percent of the operating costs for the two industrials.

These are industries that are far more reliant on gas, and far less economically productive with it, than competitors. The gas boilers used by Fonterra and other processors, for example, produce $45 to $75 in GDP for every gigajoule of gas.

At the same time, these industrials will find it easier to move away from gas – one of the key recommendations of the report. Switching could be accelerated by a $100 to $200 million government fund, with competitive reverse auctions rewarding cash to the lowest cost per GJ bids.

BCG estimated such a fund could move 10 to 20 PJ of gas demand to biofuels and electricity. That was an outcome far better than if industrials (beyond low-productivity Methanex and Ballance) close down.

“The first PJ of demand destruction (after a Methanex and Ballance exit) equates to roughly $400 million in GDP loss, but the tenth incremental PJ corresponds to around $700 million. In total, 5 PJ of lost demand risks up to $3 billion in annual GDP losses, and 10 PJ could reach $7.3 billion p.a. which is nearly 2 percent of GDP,” the report found.

The renewable revolution

Shoring up supply of gas and reducing demand by industrials would put downward pressure on gas prices, which in turn would flow on to electricity prices. But the single greatest lever for reducing the wholesale price of power is burning less gas for power.

Building new renewables to displace gas generation could have a disproportionate impact on power prices. Electricity prices have remained flat in real terms for residential and commercial users and wholesale prices are expected to decline in the coming years, BCG found.

That may not flow through to a lower power bill for households; however – the cost of lines upgrades will spike over the coming years, adding to bills even if the power generation itself gets cheaper. Lines charges already make up 35 to 45 percent of residential bills and will increase by 25 to 35 percent by 2030.

Nonetheless, avoiding spot price spikes as seen last winter could avoid heaping further burdens on households and keep electricity-intensive industrials running.

Achieving this requires transitioning gas from a base load, always-on fuel in the power system to one used for intra-week low periods (low-wind and dry periods) and as support in dry years.

In 2024, despite the dry year and coal burning, renewables made up 85 percent of generation. Gas was about two-thirds of the remaining 15 percent. Despite that, it set the wholesale price of power 90 percent of the time.

As renewable penetration rises above 90 percent, the frequency at which expensive gas sets the price of power diminishes. In a 95 percent renewable system – which we are projected to hit by 2027 with just the wind and solar farms already under construction – gas sets the price just 50 to 60 percent of the time.

By 2030, if the rate of renewable build-out increases, New Zealand could achieve a 98 percent renewable power system in normal hydrological years, dropping to 92 percent in dry years. In normal years, gas would set the wholesale price just 25 to 35 percent of the time.

In other words, gas’ influence on the price of power could be slashed by more than two thirds, simply by continuing to build renewables at the rate we are already constructing them.

“The build-out of renewable electricity is really important for affordability. There might be some misunderstandings from some, who think that renewable electricity does not help affordability, but it really will once we get into those high percentages of renewables,” Hobbs said.