According to the jacket copy for Dark Renaissance, Professor Stephen Greenblatt has been “studying, thinking and writing about Renaissance literature his entire working life”. Lurking behind this rather bold claim, there’s a more fascinating disclosure that holds the key to every page within: the scholarly refutation of a literary myth – Christopher Marlowe, the Elizabethan spy-playwright murdered in a tavern brawl.

Shakespeare scholars sometimes concede, anecdotally, that if Shakespeare had died before Marlowe, we should now regard Marlowe as the greater writer.

In this book, Greenblatt has translated a donnish provocation into the sinews of an unforgettable literary biographical tour de force. Almost single-handed, he has curated a rehabilitation of Marlowe’s reputation as the greatest rival, collaborator and exact contemporary of the glover’s boy from Stratford.

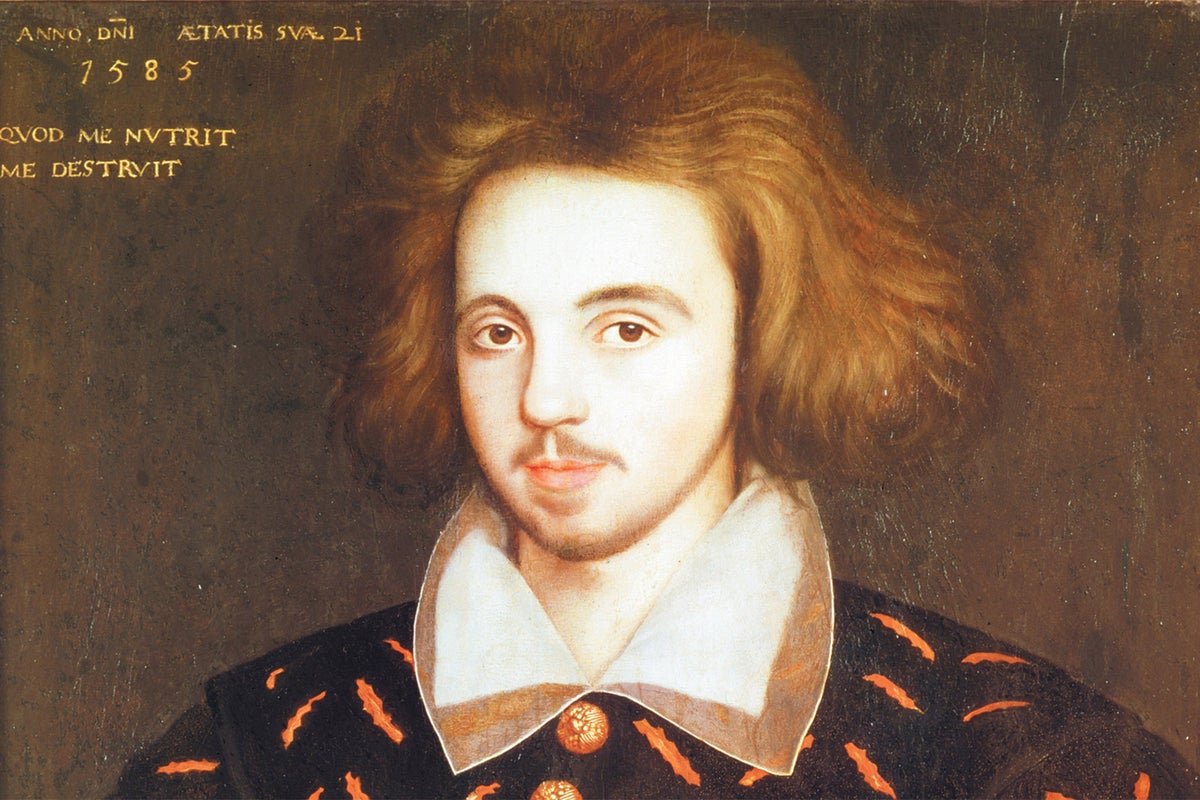

Today, in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where Marlowe was an impecunious scholar from 1580 to 1585, the famous portrait – believed to show the poet at 21 years old – has been moved from an obscure corner of the college dining hall to a place of honour in the Fellows’ inner sanctum, where it now hangs, radiating dark mystery like an icon.

Not only has Greenblatt achieved this profoundly influential reappraisal in books such as Will in the World, his bestselling life of Shakespeare, but in popular culture, he has also championed the immense significance of Marlowe the poet and playwright in the late flowering of Elizabethan arts and letters.

In a tantalising aside at the end of this enthralling analysis, Greenblatt describes how, when asked about his ideas for a Shakespeare biopic, he advised Tom Stoppard’s co-writer “to forget Shakespeare” and write a movie about Marlowe. No surprise, then, that some of the wittiest and most brilliant lines in the Oscar-winning Shakespeare in Love are actually about Kit Marlowe, played by Rupert Everett.

Dark Renaissance brings the wheel full circle. Greenblatt, having confessed his “fascination” with the author of Tamburlaine, Dr Faustus and The Jew of Malta, captures the pivotal moment when Marlowe’s unforgettable, mighty lines (“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?”) wowed London audiences during the years before and after the Spanish Armada.

Here, once and for all, in a profound meditation on the well-springs of creativity, Greenblatt nails the playwright’s staggering originality: his fleeting role (six years at best) in the making of that glorious world-class dramatic phenomenon, Elizabethan theatre.

Dark Renaissance is a book with many messages, but it starts in the bitter cold of late Tudor England, a peculiar society, estranged from Europe and locked in a savage internal war with itself about its state religion and the security of the realm. Still semi-literate, England was scorned by one European scholar as a place of “obstinate pedantry, ignorance, and conceit”, with a “rustic rudeness” that’s not unknown even today.

open image in gallery

If Marlowe hadn’t died such an untimely death, could he have eclipsed Shakespeare as the greatest writer? (National Portrait Gallery)

The world into which Marlowe was born in 1564 was dark, violent, primitive and savage. The earth was at the centre of a universe ruled by God and a divinely appointed monarch. The English Renaissance would change everything. Within a generation, perhaps as soon as the 1620s, which saw the publication of the First Folio, this becomes the insular society we can begin to recognise as the precursor to our own.

Greenblatt describes Kit Marlowe, the son of a Canterbury shoemaker, as “a perfect nobody” whose scholarship to Corpus Christi College, the home of the fabulous Parker Library, liberated his dormant creativity through an “Italy of the mind”. The classics of Latin and Greek – Aeschylus, Sophocles, Ovid and Horace – turned the key on a treasury of ideas and sensations hitherto undreamt of. Still at university, this perfect nobody was recruited to “Her Majesty’s good service” in the secret state, five of whose servants, including the lord chancellor, would lobby for Marlowe’s MA when covert travels interrupted his studies.

Within five years of arriving in Cambridge, this supremely gifted scholar and outsider was advertising his newfound self, borrowed robes and all, in the famous Corpus portrait. He’d also begun to experiment with an astounding new drama about Tamburlaine the Great in iambic pentameter, the new and addictive medium known to the playhouses as blank verse. Not for the first time in the English tradition, theatre and espionage seemed to coexist.

open image in gallery

Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where Marlowe was a scholar from 1580 to 1585 (Wiki Commons)

Simultaneously a stellar celebrity and the murky confidant of the omniscient spymaster Francis Walsingham, Marlowe falls into bad company. Among vicious dissimulators like Richard Baines and treacherous “Sweet Robin” Poley, Marlowe becomes trapped in the toils of a dark and relentless community from which there is no respite. In the haunting words of Dr Faustus: “The stars move still, time runs, the clock will strike.”

The professor of the Renaissance who advised the authors of Shakespeare in Love to make a Marlowe movie is too good a scholar to fall for the sinister plotting that led to Marlowe’s murder in Deptford on 30 May 1593. Just as Greenblatt resists the temptation to over-anatomise the atheist, gay Marlowe, so he characterises the career of the clandestine playwright as a tragic misstep, the Faustian pact that would culminate in his fatal “reckoning”.

The climax of Dark Renaissance inevitably focuses on that long lunch by the Thames in Deptford, and the alleged dispute over “the bill”. Ironically, in a life where so much is conjecture, the uncontested facts of Marlowe’s death were on the record within days of his killing. As to the motive and the cue, Greenblatt wisely judges that “the case remains open”, discounting the arguments made by Charles Nicholl in The Reckoning. After 400 years, it’s hard to imagine what new, clinching evidence could resolve that controversy.

open image in gallery

‘Greenblatt’s case for Marlowe to be reconsidered is made with exhilarating clarity and economy’ (Penguin Random House)

Besides, Greenblatt has already brought his analysis of the playwright’s life and work to a fitting close in an impassioned, valedictory consideration of Dr Faustus (and Edward II), among the most arresting chapters in a book replete with dazzling close-reading. This brilliant portrait of a strangely modern, tragic figure, whose “fatal genius” became the catalyst for this earthquake in English literature and culture, establishes his twinship with Stratford’s genius.

Like Shakespeare, Marlowe drew on his own blood to animate his characters. His ambitious spirit haunts his Tamburlaine, his Edward II, and his Jew of Malta. Dr Faustus is equally in thrall to “the joy of serious study”, a joy also celebrated by Greenblatt himself.

The pact that Faustus makes with Mephistopheles recapitulates Marlowe’s own experience as a young man who dreamed a dream of an extraordinary life, inspired by books, that ultimately became a nightmare. As memorably as Shakespeare, he articulates a most profound moment of existential dread in vernacular monosyllables: “Why this is Hell, nor am I out of it.”

Greenblatt’s case for Marlowe to be reconsidered is made with exhilarating clarity and economy. The glover’s boy and the cobbler’s son shared a creative symbiosis. The one would not have emerged without the other. No one who cares about the creative DNA of English theatre will read a more enthralling or majestic account of its dangerous origins this year.

Dark Renaissance by Stephen Greenblatt (Bodley Head, £25)