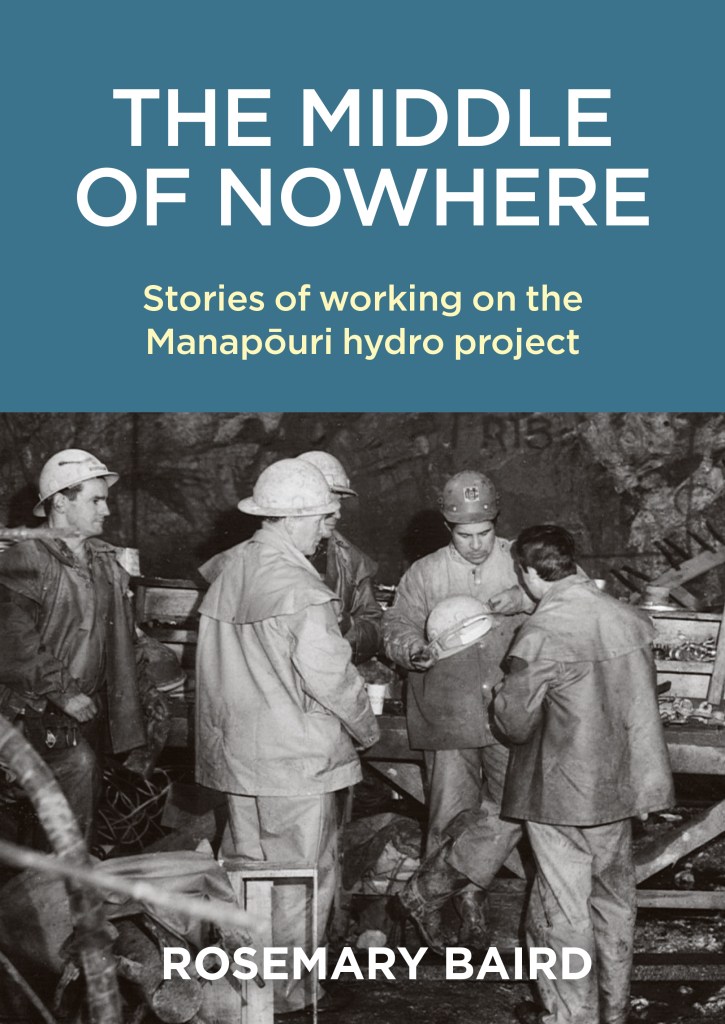

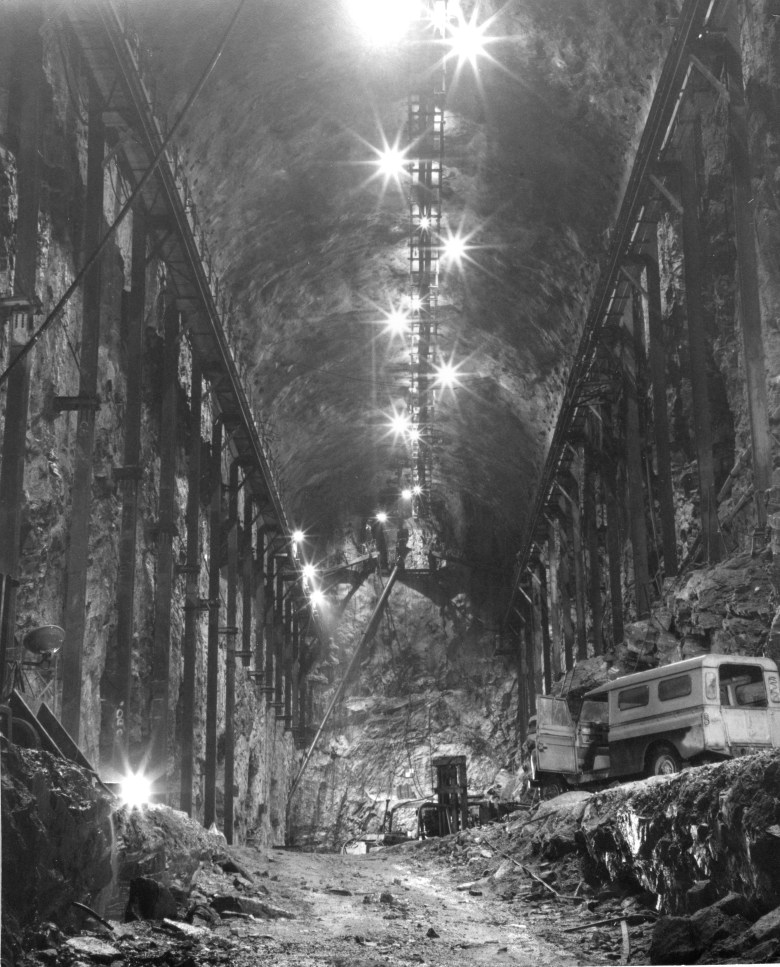

We have a winner, surely, of the award for best illustrated book of the year, in the surprise bestseller The Middle of Nowhere: Stories of working in the Manapōuri hydro project by Rosemary Baird. The photos are magnificent. They show the result of hard work and good wages in a golden age of industrial relations. They show that massive post-colonial masterpiece, Manapōuri, built between 1963-71, capitalising on the Cook Strait cable which allowed the South Island to send power to the masses in the North Island. They show the making of New Zealand. The incredible image below shows the huge machine hall at West Arm under construction: all at once it brings to life the meaningful statistics that went into building the hydro project, such as seven turbines driving seven 100MW generators and that 18 men were killed on the job.

Dorothy Kitchingman Collection

Dorothy Kitchingman Collection

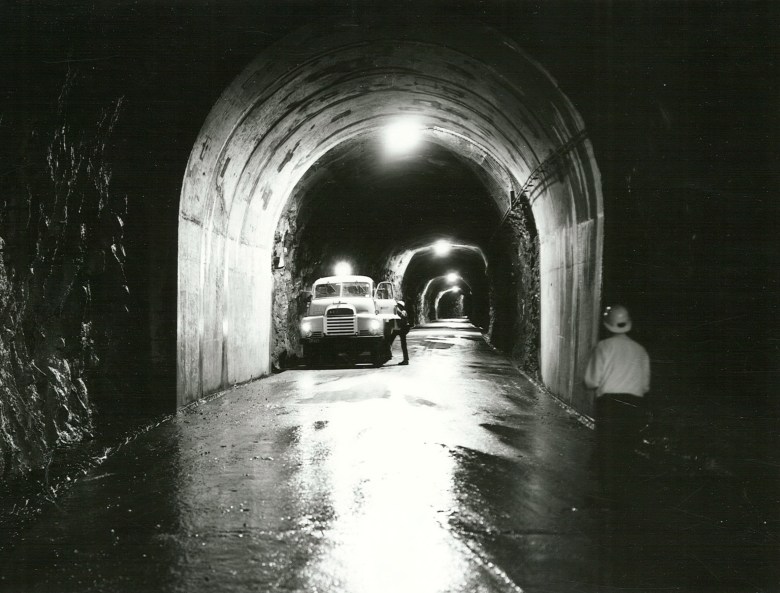

The book is more than photographs. It’s the vision of oral historian Rosemary Baird, who first stumbled onto the idea for the book when she interviewed Frank Pawson in 2009 for her PhD on Kiwis who emigrated to Australia between 1965-1995. “And then it happened,” she writes, thrillingly, in her Introduction. “That magical moment when an interviewee breaks off into an area of their life story about which you had no idea.” Pawson started talking about working at Manapōuri. Baird was hooked. She sought out other workers and held onto her conviction that a book on the hydro scheme would amount to a valuable social document. Bravo to Canterbury Unversity Press for taking the idea onboard. The stories take you there and the photos, sometimes, take you to another planet, such as another incredible image, below, of the spiral tunnel at West Arm.

Photographer: J. Waddington, Ref: R24802965, Archives New Zealand

Photographer: J. Waddington, Ref: R24802965, Archives New Zealand

The project was headed by Americans. Some were great, some were appalling. Baird interviews a worker who tells her that a boss from Utah called a group of Māori “n***ers.” (Interestingly, the book uses the whole word). He was fired and put on the first plane back to the States. Race is one of Baird’s subjects, along with class, sex, family life, working conditions, leisure, isolation and depression. Single men were accommodated in huts; married men moved to a purpose-built village, which bears a close resemblance to Hell, as pictured below.

The semi-ironic caption in the book reads, ‘Gardening work carried out by a keen tenant.’ Meridian Energy, 1966

The semi-ironic caption in the book reads, ‘Gardening work carried out by a keen tenant.’ Meridian Energy, 1966

It snowed, the rain was endless, there was a driving wind. The mountains formed a barrier and a sense of entrapment. One worker says, “The river ran through everything.” Another remembers, “Everything was wet. Your bed was wet, your clothes were wet.” There was half-an-hour of sunlight in the short days of winter. And then there were the sandflies. A worker from Poland suffered badly from the bites, and had permanently swollen hands. But it wasn’t all terrible. The most articulate voice throughout the book belongs to Tim Shadbolt: he gave Baird a fantastic interview (an excerpt appeared at ReadingRoom), and remembers things with detail and humour of his time working on the project. He talks of lying in his hut with the heater on, perfectly content, “all warm and cosy.” Good old Tim. He seems to have lived his entire life (including his colourful political career) as a sunny optimist. For many other workers at Manapōuri, though, the experience was was something to forget. You can see it in the posture of the guys (and the space around them) in the image below of the West Arm construction camp main dining room.

Photo from Meridian Energy, 1966.

Photo from Meridian Energy, 1966.

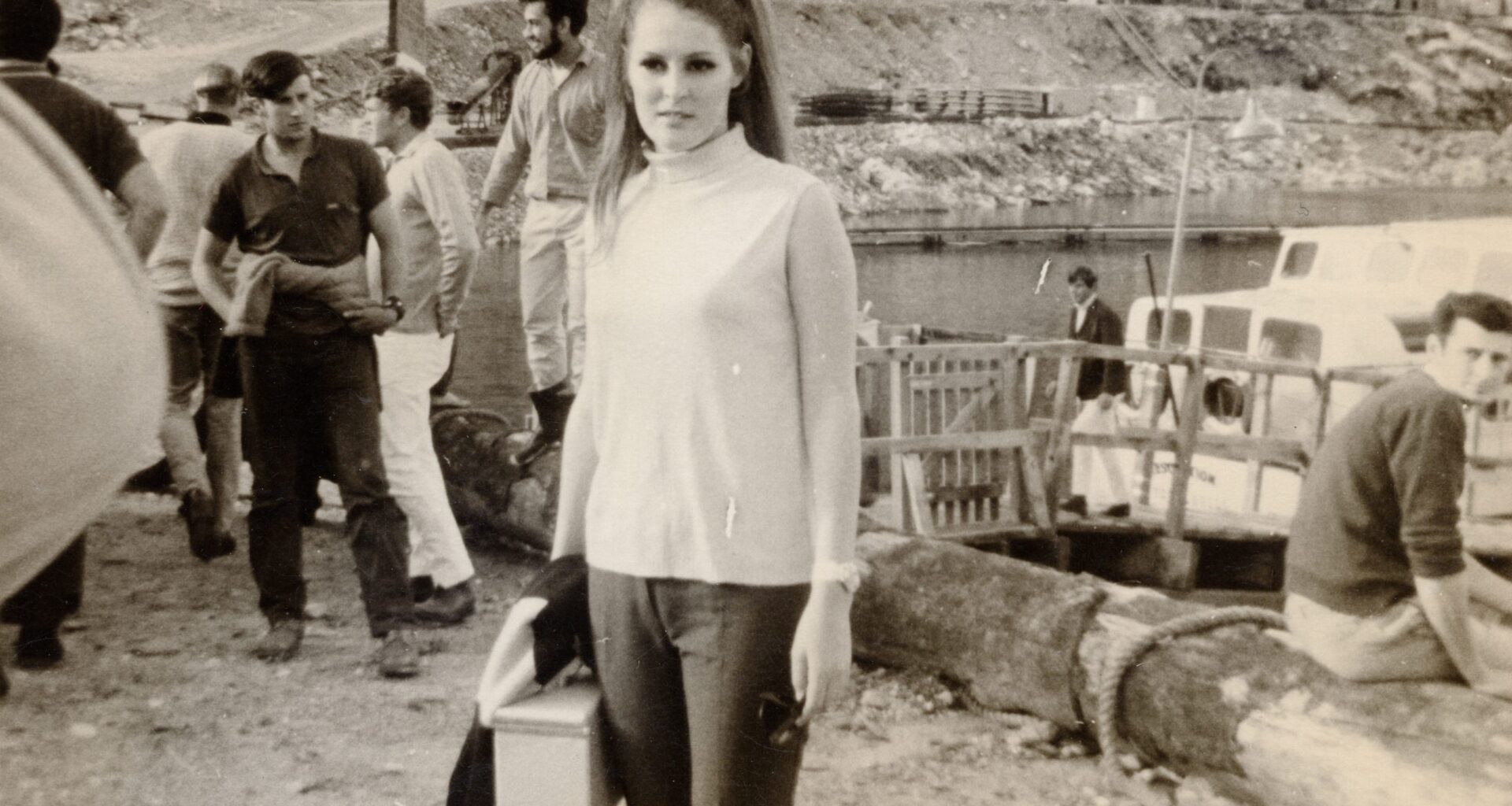

It was the days of the Holy Smoko. Crews stopped work on the dot at 10am and 2:30pm for morning and afternoon tea. The food was good: “You ate like a king.” Chops and poached eggs for breakfast, fish cakes and spaghetti (!) for lunch, deepfried blue cod with creamed potato for dinner, banana custard and fresh cream for dessert. There was a gumboot allowance, an isolation allowance, a tar allowance, a sewage allowance. Workers could save every penny they earned if they wanted to (they had free bed and board) but many blew their wages on booze and gambling. “Alcohol was the lifeblood of the project.” There were affairs in the village, even a Peeping Tom. Shadbolt took up boxing and slept with the trainer’s wife. Baird interviews one of the nurses who worked there, pictured below; she talks of feeling eyes on her whenever she entered a room.

Photographer: Mr Neill, Ref: R24730771, Archives New Zealand

Photographer: Mr Neill, Ref: R24730771, Archives New Zealand

The end pages of the book are a roll-call of the 18 men who died at Manapōuri, and how they were killed. There was the man killed by a concrete mixer pulled out by a locomotive. “He was collected up in a plastic bag.” There was the father of six who stepped backwards onto the tracks and was run over by a diesel locomotive. The book is a record of tragedy, also achievement, the making of something extraordinary. Baird does it all justice. The engineering masterpiece of Manapōuri remains intact; Baird went to the site and took this image, below, of the power station machine hall in 2017. Her book is a record of ghosts in the machine.

The Middle of Nowhere: Stories of working in the Manapōuri hydro project by Rosemary Baird (Canterbury University Press, $59.99) is available in bookstores nationwide.