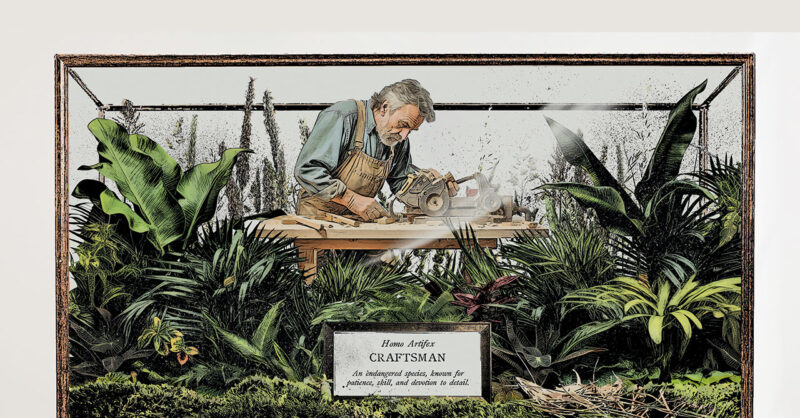

Illustration by Gregori Saavedra

When I was 11, my father announced one of his surprise trips. We were going, he explained, to visit a dry-stone waller who lived in the Black Mountains in Wales. “He used to be a priest,” Dad explained, “but he’s moved on from that.” This invited me to imagine a superficial narrative: that his friend had given up God, but instead found nature, and with it a peculiar and hardy craft. But as the experience unfolded, the superficial narrative gave way to a more subtle and interesting one: that the purposeful mingling and interaction of both nature and craft could lead to its own kind of transcendence. As we drove away from his friend’s house nestled in the hills, it seemed less a question of religion vs craft, and instead more a matter of religion via craft.

James Fox’s superb new book Craftland – a journey through Britain’s lost arts and vanishing trades, begins with the author’s immersion in dry-stone walling. It is one of my favourite chapters in a book with many highlights. Dry-stone walls, with no mortar to act as glue, “are bound only by gravity and friction,” like assembling a 3D jigsaw puzzle that is different every time. “In a society that craves clicks, likes and quick returns,” Fox observes, it’s hard to weigh the back-breaking (and terribly paid) struggle to create a wall designed to last 200 years. But what about the rest of us: will what we are doing today still be around then? “The only thing I care about,” one waller explains to Fox, “is making something that will stand in the landscape after I’m gone. That’s all the credit I need.” Each of the subjects in Craftland would probably agree with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s adage that “the reward of a thing well done is to have done it”.

Fox is a Cambridge academic who has made a name as an art historian – authoring The World According to Colour (2021) and breathing new life into television history with a number of unapologetically intelligent BBC programmes – but he is probably better described as a cultural historian. He is an interpreter of all types of traces and clues, wherever the trail might lead to a deeper understanding of what makes us human. His specialty is identifying, disentangling and explaining the hidden drive that sustains human excellence – the urge to overcome, but also to leave something behind.

People who excel at things often don’t have a clue why – they may need a real critic to understand and explain their work on their behalf. That is what Fox does in Craftland: he brings his critical intelligence to platform the usually silent process of mastering a craft. I read the book with admiration not only for its remarkable subjects individually, but also the human spirit that unites them all. It’s no stretch to say that you don’t have to have any interest in craft to enjoy Craftland – because the subliminal subject is us, especially the ways in which we might be losing our way.

Fox’s interwoven stories reveal a great deal about mastery more generally – whether it belongs to the category of craft or otherwise. The interplay of intuition and deep knowledge, for instance. When the lettercutter Lida Cardozo carves her designs she “makes dozens of unexplainable decisions every second, which after decades of practice are close to automatic.” That, as I know well from my own tribe, is exactly how a master batsman in cricket selects which shot to play: expertise that emerges as instinct. Experience, acquired by close attention, surfaces as an intuitive spontaneity that borders on the carefree. In my idiosyncratic reading of Craftland, I saw how – if his career had taken a very different path – Fox could have become the best sportswriter of his generation.

Much of Craftland is concerned with the nuts and bolts. Fox is determined to take us far away from the sanitised craft-shop cliché, and for us to learn what it’s really like to make lobster pots, wheel spokes or whiskey casks. But amid all the practical exploration and careful reporting, you occasionally see that Fox is attuned to deeper rhythms. He describes how a rush weaver read an inspiring craft paperback, and “pored over its pages like a seminarian studying a bible”. By the end of each chapter, the craft under review starts to feel like the construction of a cathedral, a massive and interconnected collective effort, spanning countless generations – “surrendering oneself to one’s vocation, subsuming one’s ambitions to the collective good, and committing oneself to excellence for its own sake.”

One thread I hadn’t anticipated was the way many crafts have intense jeopardy embedded in the process: you might only get one shot at it, like painting a fresco. A visit to Britain’s last bell-maker, John Taylor & Co in Loughborough, reveals how a bell will often crack in the process of being formed, even after painstaking preparation. Patience, planning and ritual only get you so far – then you’ve got to execute it just right.

Subscribe to The New Statesman today from only £8.99 per month

The backdrop to Craftland is a very different world, usually just out of sight in the book, though never far from the daily experience of the reader: fast fashion, careless design, ugly things made to be thrown away, buildings designed by CGI rather than humans. We might call it Uncraftland. Fox mainly leaves the barren flatness of Uncraftland implied, but occasionally he lets down his guard, contempt pouring on to the page, and our guide turns moralist. This is Fox’s summary of what the endurance and revival of craft is reacting against:

Many goods have such short lifespans that they are effectively created in order to be destroyed – used once, for a few bathetic moments, before being replaced by equally throw-away successors. Much of the world’s culture now takes place in virtual rather than physical space, stored in remote server farms, rooted only in binary code, of unproven longevity.

This leads Fox to the best case study in Craftland: “Lettercutters belong to the resistance,” he writes. “They stand for materiality, for slowness, for permanence – immovable rocks in a gathering virtual storm.”

Fox visits the Cardozo Kindersley studio in Cambridge, where the concept of analogue is pushed to the limit: “There are no humming computers or bleating phones,” Fox reports, “mobile phones are prohibited in the workshop – as is everything else with a screen.” Just above Lida Cardozo’s easel is a phrase that has become the firm’s motto: “Hasten slowly.”

Chiselling letters into stone cannot be undone, “its practitioners facing the same pressure as a footballer in a penalty shoot-out or a gymnast mounting the rings”. But that subliminal pressure is balanced by the feeling of continuity. “I like the idea of an upward spiral,” Cardozo says. “You hand it on, then the next person refines and makes it better.” Fox ends the chapter by reflecting that we still take care about permanence in lettering, but usually only on gravestones. If we thought more often about our own transience, he implies, we’d create more things built to last.

“You can learn everything about a society from its tools,” a Sheffield cutler tells Fox. “A good hand-made tool,” Fox concludes, “has the power to elevate everyday life. It can spark joy when you least expect, turning mundane routines into rituals… Before you know it, without even realising it, you are transformed into a craftsperson yourself, as if the object has quietly passed the spirit of creation from the maker on to you.”

In the 1980s, I’d glimpse my father writing his novels in pencil. He’d start by sharpening ten 3B pencils (very soft lead, almost eager to mark the page), which he’d use in sequence until all ten needed sharpening again. So the process was not only analogue, but also had built-in breaks, which had the potential to prompt review and reflection. The book was only separated from the direct touch of the human hand when a first draft was finished, and Dad would send the whole manuscript to a typist.

It’s even harder to concentrate and to connect with one’s work now than 40 years ago. So instead of switching off email and continuing to type on this laptop, I shall try writing my next book long-hand, on paper that I can touch and with pencils I can hold.

Indulge me one final family reflection. Every year, in early spring, I take my son (now 12) to a famous cricket bat factory near us. They still make the top-end bats by hand. Is the trip for my son to get a new bat, or for me to be around the things that used to define me? Because I’ve never felt any day to be wasted when stood among willow shavings, picking up clefts, feeling for something in the wood without knowing exactly what. Weight, yes; balance, certainly. But perhaps something more fundamental, too. Idly picking up those bats is also about renewing and reconnecting – with the game’s past, the game’s future, and the natural world that sustains it.

Craftland: A Journey Through Britain’s Lost Arts and Vanishing Trades

James Fox

Bodley Head, 368pp, £25

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

[See also: The age of deportation]

Content from our partners

This article appears in the 10 Sep 2025 issue of the New Statesman, The Fight Back