In the shifting sands of local politics, the longevity of The People’s Choice in Christchurch is an outlier.

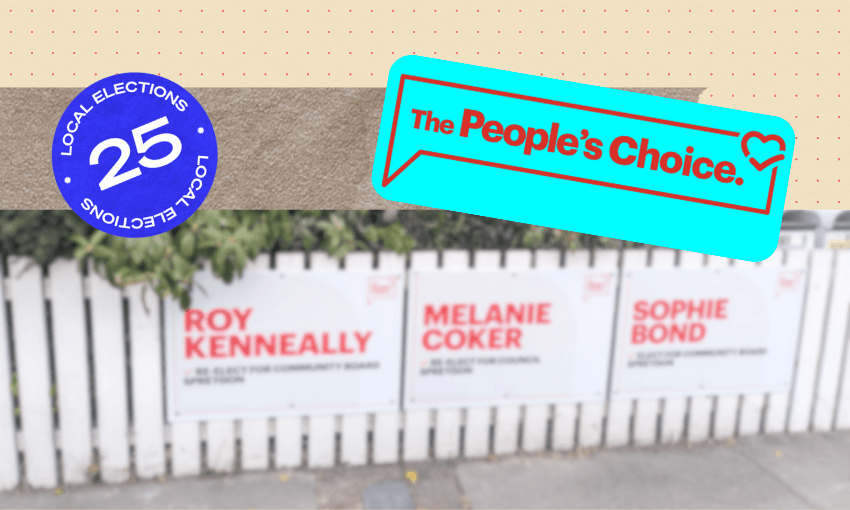

Around Ōtautahi, there’s one reliable aspect of election season: dozens of hoardings around the city emblazoned with the logo of The People’s Choice (TPC). More than a statement of democracy, the name belongs to one of the biggest, most consistent local elections tickets in the country.

“It’s a big-tent progressive ticket with a focus on community, environment and public ownership and social justice,” says Paul McMahon, co-chair of the group. He is also campaigning to retain his role on the Linwood community board, one of 35 TPC candidates across Christchurch City Council, Environment Canterbury and Christchurch community boards. McMahon has been part of The People’s Choice for two decades, back when it was known as Christchurch 2021.

In a political context, a ticket is a loose grouping of aligned candidates, like a party but less formal. They’re common in New Zealand local body politics, which national political parties have traditionally tried to distance themselves from to varying degrees.

Paul McMahon has been involved with The People’s Choice (formerly Christchurch 2021) for two decades. (Image: Shanti Mathias)

Formed 30 years ago, to contest the 1995 local elections, The People’s Choice has variously been affiliated with Labour, the Alliance and the Green Party. Currently, it’s strongly aligned with Labour – it gets support and volunteers from local Labour electorate groups – and has a memorandum of understanding with the Green Party, and several Green Party members running under its banner. Candidates who are Labour members will have “The People’s Choice – Labour” listed as their affiliation on voting forms, but the central Labour Party doesn’t decide policy.

The alumni list is distinguished. Megan Woods was The People’s Choice’s mayoral candidate in 2007, and Jim Anderton (whose fingerprints are all over much of Christchurch politics) suggested the rebrand from Christchurch 2021 in 2010, when he was running for mayor too.

Former minister (and People’s Choice candidate) Megan Woods, photographed in her Beehive office by Michelle Langstone

Local politics is changeable: it has neither the budgets nor the prestige of central government elections. How, then, has The People’s Choice lasted this long?

Money is one reason. Part of agreeing to be a People’s Choice candidate is a commitment to give part of your stipend as a councillor/community board member back into the organisation. “You’re expected to pay into that fund,” McMahon says. To Melanie Coker, current Christchurch councillor for Spreydon and People’s Choice campaign chair, that leads to better political representation. “We give opportunities to individuals to run for election with fewer resources who wouldn’t run by themselves,” she says. “We have a wider range of candidates, more women and people of different ethnicities.”

New candidates are given advice and support on campaigning “to have the confidence to really connect with voters”, Coker says. McMahon is big on candidates meeting people in person as much as possible. “You need to disabuse candidates of the idea that spending a bunch of time on social media is worthwhile.”

Work begins nearly a year before elections – for 2025, The People’s Choice convened a strategy panel in November, which called for nominations and selected Coker as campaign chair. April, May and June are for confirming selections. “Every time, we say we should do it in March,” says McMahon. “But that never happens.”

Nathaniel Herz Jardine is running as a People’s Choice candidate in Heathcote (Image: Shanti Mathias)

Nathaniel Herz Jardine is one new candidate, campaigning for a council seat in Heathcote. He says the selection process was fairly straightforward. “It was sort of like a job interview,” he says. Candidates gave a speech to the selection panel, who then decided which candidates they would support. While candidates agree on core policy – The People’s Choice has a 2025-2028 vision, featuring pest control, te Tiriti partnership, mass rapid transit, and publicly owned water and electricity assets – candidates can decide on local issues to champion without the need to caucus.

“I’ve decided on most of my priorities from doorknocking,” says Herz Jardine. “Rates are really high for people who have retired, people are frustrated there aren’t enough transport options.”

McMahon is acutely aware that “there’s a smaller chunk of people who vote in the body election and they skew a bit more to the right”. The People’s Choice and its Labour affiliation won’t win everywhere. In Harewood, for example, where right-wing councillor Aaron Keown was reelected unopposed, “I don’t think a People’s Choice branded candidate could win,” McMahon says.

The group tries to be strategic about its campaigns. “We don’t think it’s an imperative to run everywhere – we’re prioritising areas which we think are the best use of our resources.” The People’s Choice has nine candidates running for Christchurch City Council, where there are 17 total seats, and five Environment Canterbury candidates running in Christchurch seats. Altogether, this covers much of the city, sticking to Christchurch and not extending into other areas like Selwyn or Waimakiriri councils. If past elections are anything to go by, their success is likely: in 2022, The People’s Choice ran 30 candidates, winning all but one community board position, six city councillor roles and two seats on Environment Canterbury.

Does it actually help to have the name recognition of a ticket? After all, most people don’t vote in local elections, and The People’s Choice has limited visibility between campaign seasons. “Most people don’t know much about The People’s Choice,” says Herz Jardine, who is doorknocking when I call him, somewhere on a windy hill that keeps nearly snatching his words away. He estimates that only 5-10% of people recognise the affiliation when he introduces himself. All elections in Canterbury are first past the post, so each contest runs separately.

Maybe the name recognition of The People’s Choice is less important than the institution itself. McMahon points out that a key difference between local and central politics is that no matter who is elected, there’s no opposition and governing parties on opposite benches. No matter how bitter the disputes, “you’re all in governance together”. So perhaps the most useful part of joining The People’s Choice is what happens after an election. Coker says it makes a difference knowing there are other elected members who will support her at the council table. “It can get stressful,” she says. “If we get elected we can advocate together.”