For me, the single most beautiful room of the twentieth century is the underground hall of Mayakovskaya Metro Station in the centre of Moscow, which was designed in 1936 and opened in 1938. Named after the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who had committed suicide in 1930, it is a collaboration between the Ukrainian architect Aleksei Dushkin and the Russian painter Aleksandr Deineka. The architecture is a dream fusion of Constructivism, in its rhythmic lines and lack of historical references, with art deco, in its opulent materials, all rare marbles and chrome dressings. It has the purposeful sleekness of a car and the superfluous richness of a Fabergé egg. These clashing approaches to form and surface remain in tension, never overwhelming each other. Taking a train here occurs in a splendour beyond that imagined by most absolute monarchs.

Deineka contributed the series of mosaics which adorn the shallow domes that run the length of the concourse. ‘Twenty-Four Hours in the Land of the Soviets’ depicts in polychrome glass sporting achievements, feats of labour and scenes of everyday conviviality, in a vertiginous perspective somewhere between rococo wall paintings and the Bauhaus canvases of Oskar Schlemmer. These flamboyant images are realist, sure, and socialist, in a sense, but they lack the heaviness of ‘Socialist Realism’, the lumbering neoclassical aesthetic that became compulsory in the Stalin era. Figures appear to float in space, the impression of weightlessness evoking pure possibility. Mayakovskaya is one of the most convincing visions of a qualitatively different, qualitatively better socialist space I’ve ever seen. And it opened at the moral and human nadir of the Soviet system, in the year of the Great Terror.

This extraordinary work poses several questions: at a time when ‘leftist’, ‘formalist’ art was not just out of fashion but potentially a death sentence, how did this monument to socialist Futurism and Constructivism get built? How did Stalinism at its most bombastic and blood-soaked produce something that feels so light-hearted and free? These are among the ambiguities explored by Christina Kiaer in her new monograph, Collective Body, which argues that Deineka’s work in this period – ‘collective and corporeal’ – embodied an idiosyncratic kind of figurative Soviet modernism, which, as her subtitle has it, existed ‘at the limit of socialist realism’.

Along with a few other figures – one could mention the photomontage artists Gustavs Klutsis or Valentina Kulagina, the painters Yuri Pimenov and Aleksandr Samokhvalov, the architects Dushkin or Konstantin Melnikov – Deineka is interesting for the way he straddles the avant-garde of the twenties and high-Stalinist neoclassicism. His work has long been famous within the former USSR, but has taken some time to become better known outside of it. Born in Kursk, in western Russia, and trained at VKhUTEMAS, the now-mythic ‘Soviet Bauhaus’, Deineka developed his style as a painter through working as an illustrator, largely for the anticlerical magazine Bezbozhnik u Stanka (‘Atheist at the Workbench’). His work there had a simplified, ‘comic book’ quality, later criticised by more conservative Soviet critics when he shifted onto large canvases. Deineka’s major oil paintings – large, figurative canvases, showing people at work and in political struggle, all tractors, blast furnaces and red-head-scarfed women – were on show at the centenary exhibitions of early Soviet art at London’s Royal Academy in 2017 and the Grand Palais in Paris in 2019, where they amazed critics, who were shocked that such an accomplished, original painter could have been working within the conventions of Soviet official art.

Figurative Socialist Realists ‘have often been understood as antagonists’ to modernist experiment, Kiaer notes, but Deineka approached painting ‘in a dialogue with the Constructivists, not wholly in opposition’ to them. He returned to the easel painting that the Constructivist theorists had declared obsolete, but he combined this with work for mass-market magazines and mass-produced posters that they approved of. He sat somewhere on the fence in the debates of the twenties – aloof from both the Constructivists of the LEF (Left Front of the Arts) journal and the conservative neo-Victorian realists of AKhRR (Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia), though he had stronger allegiances to the modernist figurative painting group OST (Society of Easel Artists) and the short-lived October Group, a union of avant-gardists whose journal Daesh’ featured several Deineka illustrations on its covers. Deineka was a realist uninterested in nineteenth century realist painting, and a modernist who worked mostly on old-fashioned canvas rather than in the new media of photography and film.

It may seem surprising that a self-described ‘feminist art historian’ with ‘a definite Marxist “bias” in favour of revolutionary modernist art and its inherent internationalism’ should have chosen to write a book – 25 years in the making – about Deineka, whose major work was produced in the service of the Soviet Union at its most oppressive. But Kiaer is the ideal guide to Deineka’s equivocal position in the Soviet political-aesthetic landscape. She has long been conspicuous among Anglophone historians of Soviet art for how seriously she takes the socialist project and the idea of a revolutionary art. Her first book, Imagine No Possessions (2005), was a study of a group of well-known Soviet avant-gardists – Aleksandr Rodchenko, Mayakovsky, Varvara Stepanova, Liubov Popova, Vladimir Tatlin, Sergei Tretiakov and El Lissitzky. It charted their efforts in the 1920s to create ‘socialist objects’, which, unlike capitalist commodities, were designed to be useful things, tools for creating social relations that would transcend both capitalism and the nuclear family. Neither aesthetes out of their depth, mixed up in politics they barely understood (as the Cold War interpretation would have had it) nor as Fordist, positivist technocrats (as some Western Marxist takes might assert), Kiaer recast the Constructivists as serious Marxist thinkers and doers and, particularly, as feminists. (Perhaps reflecting its Lennon-derived title, Imagine No Possessions is, I believe, unique among works of art history in inspiring a rock album – the Baltimore-based group Horse Lords’ minimalist Comradely Objects.)

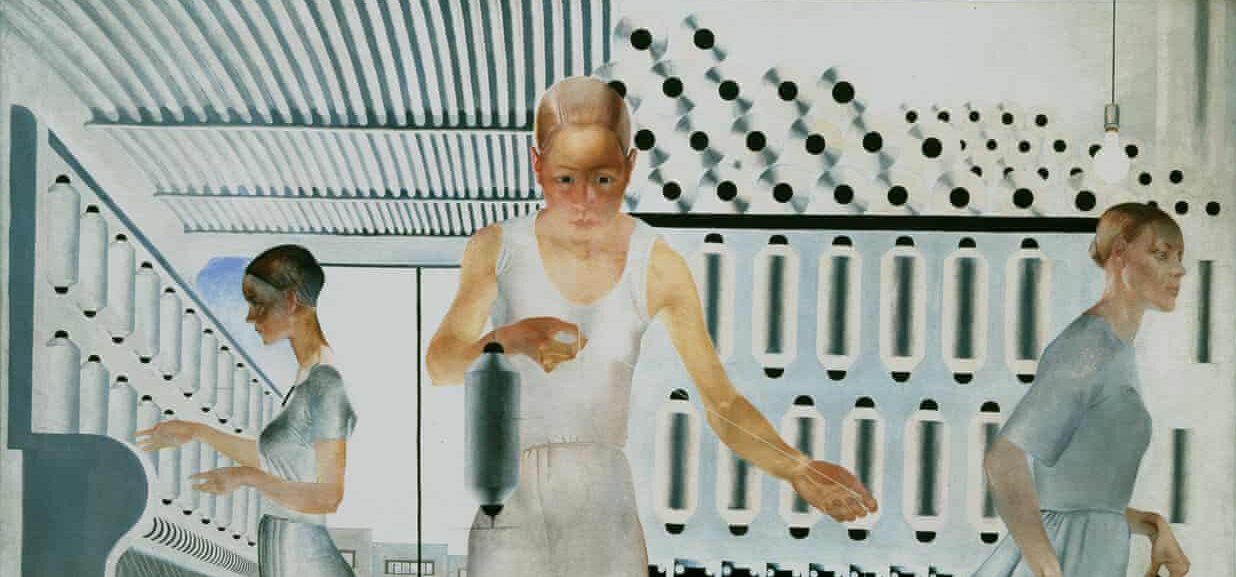

At the centre of the Collective Body is an exploration of the degree to which Deineka specialised, if not wholly intentionally, in a distinctly feminist aesthetics, in his large-scale paintings of women workers, sports players and fighters, throughout the twenties and thirties. For Kaier, ‘in his consistent refusal to depict women within conventions of femininity, sexuality and objectification, Deineka unexpectedly becomes the historical conductor – in the sense of an electrical conductor – of a profound socialist feminism’. His work for Bezbozhnik u Stanka often took up feminist causes – against wife-beating, against keeping women at home, against male drunkenness and violence and, of course, against the patriarchy of the Orthodox church – though he never explained or theorised what he was doing here. After an early line in lurid depictions of the overindulged bodies of the NEPman and NEPwoman, entrepreneurial harbingers of capitalism in the mixed economy of the 1920s, Deineka’s work quickly acquired a more liberatory emphasis on the bodies of revolutionaries and workers. In ‘The Defence of Petrograd’ (1928) – one of the great oil paintings that made his name – women stand at the centre of a laconic but monumental image of the defence of the city in the Civil War, marching as ‘signs of the promised emancipation of women under Bolshevism that enhanced the ethical superiority of the Red case in the Civil War’. Absent from the first sketches – based on Deineka’s visits to veterans at the Putilov Works – the women are a politicised, pointed addition. ‘Textile Workers’ (1927), in which women weave cloth with the precision of lab technicians in a factory that forms part of a Constructivist ideal city, is so extraordinary that these figures were only legible to critics at the Royal Academy exhibition as science-fictional ‘robots’. As Kiaer tartly notes, to uninitiated gallery-goers in London or Paris, these pictures ‘seem to come out of nowhere and lead nowhere’.

If for contemporary critics like David Arkin the women of Deineka’s paintings ‘stand in for all revolutionary workers’, for Kiaer, ‘the radicality of Deineka’s canvases is that they don’t’: they ‘retain their specificity as women’. These ‘self-possessed, proletarian bodies’ are neither conventionally athletic nor conventionally beautiful, radically unlike the neoclassical nudes of fascist painting and sculpture. They are working bodies, ordinary bodies; bulky-legged, wide-hipped, sometimes angular, sometimes muscular: a sympathetic critic at the time described them as ‘a successful attempt to find an image of a woman worker who is beautiful in a new way, in our way’. They make a point about socialism and labour, their contortion and vigour quite deliberate. For Kiaer, they are images of a collective coming into being.

Deineka’s canvases were painted from life, up to a point, but they were also driven by an obsession with representing an imagined future. Modernist architecture often appears in the backgrounds of his paintings, mostly speculative rather than actual. This is one way Deineka embodied ‘a version of the Socialist Realist aesthetic’, as Kaier argues, which notoriously defined realism as the effort to prefigure what should be, as opposed to merely representing what is. In a rare statement about his own art, Deineka put this idea in his own words: ‘you can’t depict a future neighbourhood with a Leica’ – likely a reference, Kiaer explains, to a disagreement with Rodchenko, who like much of the LEF group by the late 1920s had come to view the camera as the only instrument fit for creating a socialist art.

Deineka retreated into increasingly hoary territory as the 1930s advanced, though he at first managed to retain his integrity – his nudes and mother-and-child paintings can, according to Kiaer, be interpreted as tangible images of a socialist feminist future. His large oil painting ‘Mother’ (1932), an endlessly reproduced Soviet classic, shows a nude woman from behind holding a baby over her shoulder. Such works were hailed as ‘lyrical’, but Kiaer draws attention to the unsentimental approach Deineka takes to a conventional subject: the frame is almost photographic, more like a close-up film still than a Renaissance portrait. At the same time, he was producing surreal images of sport and labour, including the inexplicably naked volleyball players of ‘The Ball Game’ (also 1932). Kiaer still reads these as firmly feminist images – though no longer stark and industrial. And she sees in their utopian lyricism an important addition to the repertoire of Socialist Realism: ‘an attempt to rework modernist aesthetic strategies to help viewers to feel, as well as to comprehend analytically, the meanings and promises of socialism’.

One could easily connect this new orientation to the future with a shift in Stalinist aesthetics in the mid-30s, as the putatively ‘gayer, happier life’ in the aftermath of the famine and upheaval of 1929-33 necessitated a lighter, lusher art. Deineka, in this period, travelled to the US, which had attracted many Soviet avant-gardists (and like most Soviet visitors, he was particularly drawn to Harlem). Perhaps on the basis of the international interest in his work, he was selected to paint a mural for the Soviet Pavilion of the Paris Expo of 1937, in which, notoriously, classicising pavilions from the USSR and Nazi Germany practically headbutted each other from opposites sides of the Eiffel Tower. But Deineka, increasingly regarded with suspicion within the USSR, wasn’t allowed to travel to paint the mural himself in situ. As executed, ‘Illustrious People of the Land of the Soviets’ is a rather gross image: its subjects, selected not by the painter but by a curatorial committee, are not ordinary toiling women and men but oversized figures, based on actual ‘Shock’ workers and Stakhanovites, though equipped with Marvel Comics jawbones. Deineka’s paintings soon became bigger, grander: in the same year, ‘At the Women’s Meeting’ displayed a shift from the powerful, working bodies of his earlier work to elongated, fashionably dressed figures floating before a classical backdrop. The meeting is in the Columned Hall of the House of Unions, which that year served as the courtroom for the Moscow Trials. In these two paintings, the female faces once so full of concentration, intelligence and commitment now bear rictus grins.

After 1937, it was evidently no longer possible for a painter to maintain his integrity and their socialism while serving Stalinism: by 1939, Deineka had declined into the ostentatiously ‘totalitarian’ kitsch of the poster ‘A Healthy Spirit Demands a Healthy Body – K Voroshilov, 1939’, in which a man does his exercises while gazing moronically at a portrait of the Marshal of the Red Army. Kiaer almost leaves Deineka here, bar an analysis of two paintings – a 1948 self-portrait, in which he appears half-naked surrounded with Suprematist rugs and bedsheets, read by Kiaer as a half-hidden but trenchant defence of his ‘leftism’, and a 1942 canvas showing the battle for Sevastopol, which is somewhat grotesque but reveals his continuing interest in cartoonish drama and cinematic perspective. Yet Deineka painted for decades more – paintings which Kiaer does not discuss except by contrast with the feminist work of the twenties and thirties. In the forties and fifties, he moved towards monumental, sexualized female nudes, which have been celebrated in recent years in exhibitions within Russia. Kiaer laments these, and recounts seeing the then-Mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov, addressing the press at a gallery opening with his head in front of the crotch of Deineka’s 1951 ‘Bather’.

In a sense, the choice of Deineka as a way of writing about Socialist Realism is cheating, since, at least until 1937, he was exactly the sort of realist a modernist would love – surprising and imaginative, uninterested in the classical canon, politeness or precedent and open to experiment. Henri Matisse, for one, saw in Deineka a kindred spirit, praising him as the finest of Soviet artists. Both painters present a world of fulfilled sexuality and sturdy physicality, one that can be read as prelapsarian in the French case, post-capitalist in Deineka’s. But by not exploring the painter’s apparently questionable later work in any detail, Kiaer leaves us without a clear understanding of how and why it curdled into soft porn and nationalist kitsch. Perhaps this is deliberate. Though her account refuses to sugarcoat the horrific realities of the Soviet thirties, the last thing Kiaer wants to produce is yet another story of Stalinism – a term she pointedly does not use – crushing revolutionary dreams. She wants us to remember the dream – the utopian possibility – and still believes in its potential to be realised. For Kaier, Deineka’s early pictures represent a kind of Socialist Realist road not taken, and thus a still-live source of inspiration: they ‘offer a vision of what grand socialist art could have been: an idiosyncratic but affective form of modern art’, one which ‘at its best, activates and organizes affective forces for collective ends’.

Deineka’s fame would never reach the peaks of the mid-1930s again – between 1948 and 1956, his work ‘almost disappeared from public view’. After Stalin’s death, Kiaer notes, there was some resurgence: as an explicitly socialist figurative modernist, Deineka became a model for artists working in the ‘severe style’ that would dominate Soviet painting in the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras. During the war, too, he briefly came back into favour, as part of a general loosening of controls on art that went along with the communal enthusiasm of the war effort. The strongly antimodernist critic Osip Beskin gave a lecture in 1944 on the greatness of Deineka’s paintings, praising his move towards a ‘grand style’. Kiaer writes that ‘at the end of the lecture, Beskin joked that it was “still a question whether he’s a realist or not, and some have even said he’s still a formalist”’. Deineka, who had developed a drink problem after 1937, shouted from the audience: ‘who gives a damn!’ Kiaer wouldn’t go quite so far, but for her, the problem of form remains a problem of politics.

Read on: Owen Hatherley, ‘Architecture of the Future’, NLR 155.