The American bison’s homecoming to Montana was not only a triumph of nature, but it was also the start of a cultural renaissance for Native Americans in the northwest.

Once populating the grassy plains of North America in the millions, wild buffalo were brought to the brink of extinction during the quest to conquer the west in the 1800s. Over a century later, the mission to undo the damage wrought by America’s appetite for expansion has been chronicled by directors Ivan MacDonald, Ivy MacDonald and Daniel Glick in the potent new documentary “Bring Them Home” or “Aiskótáhkapiyaaya,” executive produced and narrated by Oscar nominee Lily Gladstone, who is of the Blackfeet and Nez Perce tribes.

The film, which debuted on PBS on Nov. 24, follows the Blackfoot tribes’ turbulent battle to restore the herds, reclaim their heritage and assert their sovereignty.

Gladstone told HuffPost how buffaloes, known as “iinnii” in Blackfoot language, were part of the “very fabric of our identity,” serving as an essential resource for survival and as a model of resilience.

“Iinnii are really at the center of everything for us,” Gladstone said. “We are Buffalo people, and a lot of the times we’re facing hardship, one teaching that we’re given, one bit of comfort that we’re given in hard times, is to be like buffalo,” who survive subzero temperatures during winter, and face elements and their predators head on.

Lily Gladstone, here at February’s Screen Actors Guild Awards, said bison were at the “center of everything” for Blackfoot people in a HuffPost interview about the new documentary, “Bring Them Home.”

Lily Gladstone, here at February’s Screen Actors Guild Awards, said bison were at the “center of everything” for Blackfoot people in a HuffPost interview about the new documentary, “Bring Them Home.”

Rodin Eckenroth via Getty Images

Known as “innii” in Blackfoot language, the animals’ population was numbered in the millions before the colonization of the American West.

Known as “innii” in Blackfoot language, the animals’ population was numbered in the millions before the colonization of the American West.

Blackfoot people and other Great Plains tribes had over 500 ways to use every piece of the buffalo, which provided sustenance, shelter, tools, toys and more.

“We had everything — the means to sustain a rich and healthy life was with us,” Blackfeet elder G.G. Kipp says in the film.

The Blackfoot people also understood their relationship with buffalo as comrades not conquerors.

“We’re not the top of a pyramid; we’re part of a bigger circle,” Gladstone told HuffPost. “We’re part of an ecosystem.”

Tribal elder and scholar Leroy Little Bear expands on this idea in the film.

“It was not just about subsistence,” he said. “In the native world, everything is made up of energy waves, what we refer to as the spirit. So when we say, ‘all my relations,’ it’s because I’ve got spirit but so does everything else. So they’re all my relatives.”

But as settlers trampled into Indigenous territory during America’s westward expansion, national leaders realized slaughtering and displacing hundreds of thousands of natives was not the only way to contend with what many colonizers called “the Indian problem.”

“We had everything — the means to sustain a rich and healthy life was with us.”

– Blackfeet elder G.G. Kipp

“Kill every buffalo you can. Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone,” U.S. Army General Grenville M. Dodge instructed a hunter in 1867.

In just one generation, these massacres killed enough bison to bring their population from an estimated 30 million to fewer than 1,000. It was a “campaign to divide and conquer not just people from each other but people from themselves, their culture, and for us, the buffalo,” Gladstone emphasized.

Without bison, other plants and animals which depended on them withered away, in turn fracturing the Blackfoot Confederacy’s vast territory into three reserves in Canada and a single sprawl in the U.S.

Generations of forced assimilation ensued, as Native children were torn from their families and taken to abuse-ridden boarding schools. Indigenous communities shoehorned into reservations, or other tribal enclaves elsewhere had their ceremonies and language outlawed. Those who gave birth were forcibly sterilized, and as elders died, countless traditions died with them.

The long tail of colonization left Natives isolated, alienated from economic opportunity and starved of identity.

But in spite of the devastation, the story of the Blackfeet and their buffalo was not over.

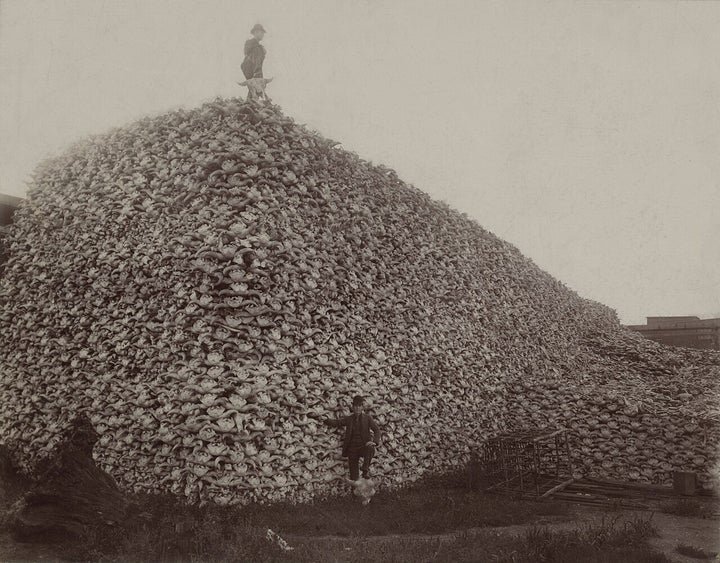

A hunter poses alongside a mountain of buffalo skulls at Michigan Carbon Works, in Rougeville, Michigan, in 1892. U.S. Army General Grenville M. Dodge once said, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

A hunter poses alongside a mountain of buffalo skulls at Michigan Carbon Works, in Rougeville, Michigan, in 1892. U.S. Army General Grenville M. Dodge once said, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

Burton Historical Collection

Gladstone told HuffPost that during “hard times,” Blackfeet people remind themselves “to be like buffalo,” who survive subzero temperatures during winter, and face elements and their predators head on.

Gladstone told HuffPost that during “hard times,” Blackfeet people remind themselves “to be like buffalo,” who survive subzero temperatures during winter, and face elements and their predators head on.

Untamed herds brought from Yellowstone National Park to Montana’s Blackfeet Reservation in 1979 mangled fences, crushed crops and grazed on cattle ground, leaving many Blackfoot to believe the beasts were nothing but a burden. Amid tension, the tribal council decided to round up the bison and sell them just years later.

“They were wild animals running loose on the Blackfeet Reservation. No one could control them,” elder and rancher Mouse Hall says in the film.

A movement to restore wild bison populations began in Canada in the early ’90s but was fraught with conflict. The fight to reunite iinnii with their homeland pitted tribal activists against Native ranchers and farmers who needed the land.

One chief’s rogue attempt to bring buffalo back to Alberta’s Blood Tribe Reserve in 1993 resulted in blockades and protests that drew national attention.

In 1998, Montana’s Blackfoot people tried again, raising a new herd of calves taught not to respect fence lines, and grow comfortable with humans with the help of Native volunteers and students at Blackfeet Community College. Still, the clashes with cattle ranchers and farm owners continued, and when a new tribal council came to power in 2006, it abruptly decided to sell most of the fledgling herd.

While the animals were mostly gone, the community’s support for rewilding had grown out of its more hands-on role with the second herd.

Conversations about iinnii’s place in Blackfoot culture continued between tribal members, bringing what Little Bear called “buffalo consciousness” back into the fold.

During those dialogues, Little Bear said he heard elders explain that while younger generations of the tribe were taught their ancestors’ stories, ceremonies and songs, those beliefs had little link to their everyday lives without being able to witness buffalo roaming free.

During dialogues about the buffalo, elders said younger generations were taught their ancestors’ stories, ceremonies and songs, but couldn’t understand things fully without being able to witness buffalo roaming free.

During dialogues about the buffalo, elders said younger generations were taught their ancestors’ stories, ceremonies and songs, but couldn’t understand things fully without being able to witness buffalo roaming free. As a keystone species, bison are crucial to the survival of other plants and animals. “Almost everything about how bison live and move through the landscape benefits other animals,” Gladstone explains in the film.

As a keystone species, bison are crucial to the survival of other plants and animals. “Almost everything about how bison live and move through the landscape benefits other animals,” Gladstone explains in the film.

In 2009, supporters continued this grassroots strategy by founding the Iinnii Initiative. They then found another base of allies with the Wildlife Conservation Society of New York City, which focused on the ecological importance of bison.

As a keystone species, the animals were crucial to other flora and fauna’s survival. When buffalo wallow in the dirt, they create nooks for amphibians, and flowers that feed insects and make up the bulk of local birds and small mammals’ diets. Their grazing creates space for grassland birds, many of which also nest in their fur. In the deep of winter, they plow through snow, treading pathways for pronghorn and other animals to survive the harsh elements.

“Almost everything about how bison live and move through the landscape benefits other animals,” Gladstone explains in the film.

Despite the conservationists’ and tribe’s different motivations, Gladstone told HuffPost that what mattered was that both were “working for the same goal,” and that the outsiders understood their role was as “allies and not saviors.”

Together, they decided to return a free-ranging herd forced from Montana’s Flathead Reservation to Canada’s Elk Island National Park by the U.S. government in the early 1900s back to Blackfeet Nation.

A group of calves were brought back to their native territory from Canada, but one key question remained: Where in the wilderness should the herd be returned?

It took years for the tribe to find the wild herd a home at Ninastako or Chief Mountain, a stretch of land at the border of Glacier National Park and the reservation which had long been a spiritual guiding point for Blackfeet.

It took years for the tribe to find the wild herd a home at Ninastako or Chief Mountain, a stretch of land at the border of Glacier National Park and the reservation which had long been a spiritual guiding point for Blackfeet.

Most of the reservation was allocated for cattle ranching, a major source of income for the tribe. Every acre of land ceded to the buffalo meant less money, so the Iinnii Initiative was forced to search for space elsewhere.

It took years to weigh the options and decide on a prime location for the Elk Island herd: Ninastako or Chief Mountain, a stretch of land at the border of Glacier National Park and the reservation which had long been a spiritual guiding point for Blackfeet.

As more years passed, the movement steadily gained momentum, leading the tribal council to set aside cattle land at Chief Mountain for the herd in 2023. That June, a herd of dozens of bulls, cows and calves returned to soil that their species had inhabited for thousands of years prior to colonization.

Tyson Running Wolf, a tribal council member, imagined the homecoming as a moment for the tribe’s “spirit to finally catch up with our humanness.”

For Gladstone, the long, arduous road to the bison’s return couldn’t have happened without the tribe echoing the animal’s own resilience.

“It takes a community of the strongest ones of them to break the embankments, to break the snow banks, to break through the storm,” she told HuffPost. “It takes a community of them to surround themselves around their calves, around the youth. It’s all of them continuing on together. And that’s as long as they’re continuing, as long as their hooves are churning and moving the earth, then we continue as well.”

“Bring Them Home” is now airing on PBS. You can find your local station’s schedule here.