Canada’s Food Price Report 2026 projects food prices will rise by another 4% to 6% next year.

For the average family of four, that means spending roughly $17,571 on groceries in 2026 – close to $1,000 more than this year. Food is now 27% more expensive than it was just five years ago.

This latest forecast simply confirms what many Canadians already experience every time they walk into a grocery store: the squeeze is no longer cyclical. It is structural.

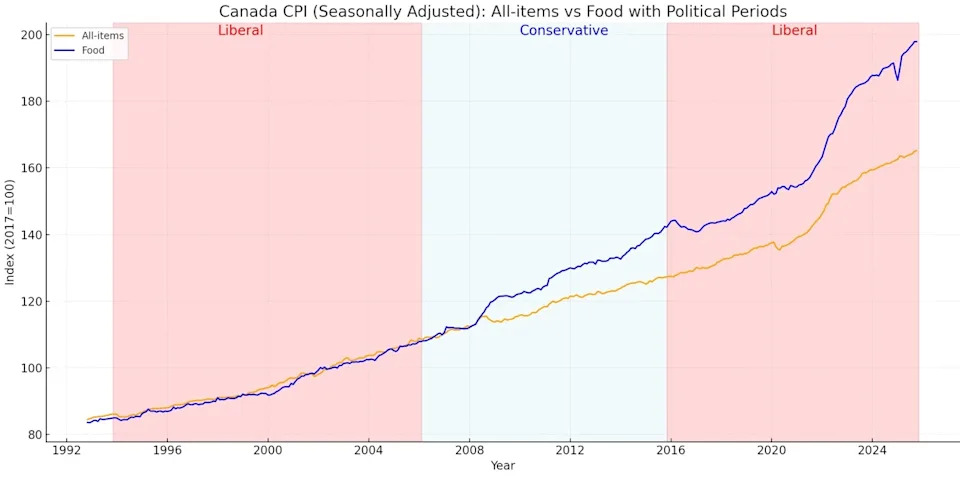

To understand where we are headed, we need to be clear about how we arrived here. A long-term review of seasonally adjusted Canadian CPI data, from 1993 to today, reveals a telling pattern. Food inflation did not begin to outpace general inflation during the pandemic, nor did it start with the global disruptions of the past four years.

The divergence – this gradual decoupling of food inflation from overall inflation – began earlier, under the Harper government, around 2008 to 2010.

Canada’s Food Price Report 2026 projects that food prices will rise by another 4% to 6% next year.

That timing matters not because it points to any single domestic policy choice, but because it underscores how global the shift truly was. The late 2000s marked the first major global food commodity crisis of the modern era. Energy prices spiked, extreme weather events disrupted harvests, and supply chains strained under growing complexity.

Canada, deeply integrated into global agricultural markets and reliant on imported inputs for food manufacturing, was inevitably pulled into these forces. The decoupling that began then has persisted ever since, through governments of all political stripes – widening further over the last four years.

Today’s food price pressures reflect accumulated, longstanding structural weaknesses: chronic underinvestment in food processing capacity, high transportation and energy costs, labour scarcity across every segment of the agri-food sector, and a retail landscape in which a small number of players exert disproportionate influence.

Add to that climate volatility, geopolitical uncertainty and the fragility of global supply chains, and the outcome is sustained food inflation that no rebate, tax credit or political announcement can easily correct.

RECOMMENDED VIDEO

A critical insight comes from Michael Graydon, CEO of Food, Health and Consumer Products of Canada. He argues Canada does not suffer from a lack of productivity because its firms are unproductive; we suffer because our manufacturing ecosystem lacks depth.

And he’s right.

Canada has world-class multinational plants operating at peak efficiency within their global networks. We also have thousands of small firms with talent, ingenuity and ambition. What we lack is a strong, scaled “middle” firms – large enough to invest in automation, advanced processing, AI and modernization.

This missing middle is where productivity gains typically emerge. Without it, fewer companies can scale, innovate, or compete. And without it, multinational firms have less incentive to assign new global mandates to Canada.

When both ends of the ecosystem – the large and the small – cannot grow together, competitiveness erodes. That erosion eventually shows up in consumer prices.

This same conclusion is reinforced in the latest Global Agri-Food Most Influential Nations Ranking prepared by Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics Lab and developed in partnership with MNP, which highlights Canada’s shrinking competitiveness in critical parts of the value chain.

The latest Food Price Report makes one thing clear: the affordability crisis is not an aberration. It is a defining characteristic of today’s food economy. Governments often respond with temporary rebates, targeted tax measures, or calls for grocers to stabilize prices, but these measures do not address the underlying issues. They are patches on a system that has been drifting for well over a decade.

If Canada is serious about improving food affordability, it must face these structural issues directly. That means reducing dependence on foreign processing, rebuilding the missing middle in manufacturing, investing in resilient regional supply chains, modernizing our transportation infrastructure, supporting innovation in food production, and strengthening competition within the retail sector.

RECOMMENDED VIDEO

It also requires acknowledging the limits of domestic policy in a world where food is traded globally and increasingly influenced by climate disruptions and geopolitical tensions.

The 2026 forecast is a reminder that the trend lines are all pointing in the same direction. Food inflation separated from general inflation more than fifteen years ago and has not converged since. The pandemic exposed the vulnerability of our supply chains, but it did not create it. Rather, it revealed the cost of ignoring long-term warning signs.

Canada now faces a choice. We can continue to treat food inflation as a temporary irritant, hoping it will fade as global conditions stabilize. Or we can confront it as the structural challenge it has become.

The data – spanning decades and multiple governments – is unequivocal: unless Canada commits to a deliberate national strategy that rebuilds depth and competitiveness in its food, health and consumer products ecosystem, the gap between food prices and household incomes will only continue to widen.

— Sylvain Charlebois is director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University, co-host of The Food Professor Podcast and visiting scholar at McGill University