Jo loves to feel the breeze blowing through her mid-city home, but for the past eight months, she said, “I’m afraid to open up the windows.”

“I make sure that every window is locked, I make sure at night I don’t turn on hardly any lights. I don’t want him to see that I’m in here,” she said.

Jo, 84, spent much of 2025 with her doors and windows closed due to her son’s repeated visits, in violation of two restraining orders due to his schizophrenia diagnosis.

Jo, 84, spent much of 2025 with her doors and windows closed due to her son’s repeated visits, in violation of two restraining orders due to his schizophrenia diagnosis.

The 84-year-old San Diego resident is hiding from her son, Ed, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and has spent much of the last 30 years in jail, prison or a state mental hospital. Last month, he was sentenced to 140 days in jail after a jury convicted him of 10 counts of violating a restraining order that forbids him from visiting her home. Ring video cameras captured Ed returning 21 times since he was released from prison on March 20.

But June Dudas, Ed’s cousin, says she holds out little hope that jail time will keep him from reappearing on his mother’s doorstep after his release in the spring. He has refused, she says, to participate in CARE Court, the state’s voluntary program that offers wrap-around services, including housing, to those with severe mental illness. A plea for conservancy, the process where a legal guardian takes over decision-making for a person who is determined to be unable to make their own decisions, has so far gone nowhere during Ed’s three jail stays this year.

While Superior Court Judge Matthew Brower said during Ed’s sentencing hearing that there “may be a conservancy effort undertaking or taking place at this time,” Dudas noted that the legal order handed down specifies only that he be offered participation in voluntary programs after he serves his jail sentence.

She struggled to contain her frustration walking out of San Diego’s central courthouse after Ed’s most recent hearing.

“There is no justice here,” she said. “There’s no justice for him and his illness, and there’s no justice for my family, for his mother.

“He will be back on the streets. To say that the only thing that we can do is incarcerate this person, even though everybody in that courtroom understood exactly what the situation was, is just unacceptable.”

It is a pattern that experts say goes far beyond one family, one that shows how recent legislation intended to reach people like Ed has fallen short.

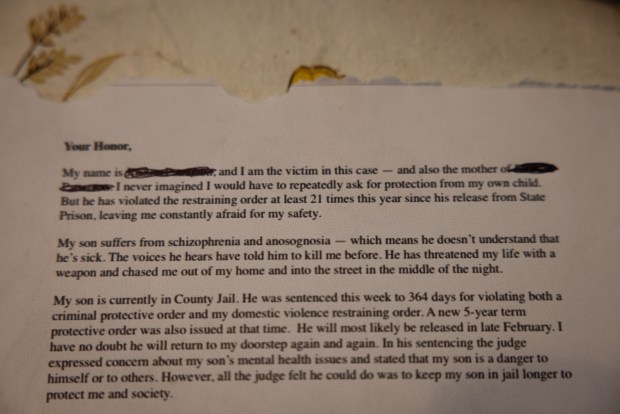

A statement made by Jo, 84, requesting the renewal of a domestic violence restraining order, made to a judge on Nov. 19, 2025. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

A statement made by Jo, 84, requesting the renewal of a domestic violence restraining order, made to a judge on Nov. 19, 2025. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Crystal Robbins, a program manager with San Diego Fire-Rescue who works with high users of emergency services, said the system sometimes struggles to handle cases like Ed’s where there is a relentless impact on family members, but for infractions that the penal code categorizes as minor. Had he, for example, punched a person in the face, as a jury decided he did to a stranger in 2020, a mental health competency examination would be more routine. That path can lead to a “Murphy” conservatorship, which the state’s Welfare and Institutions Code reserves for those charged with felonies “involving death, great bodily harm, or a serious threat to the physical well-being of another person.”

“If he had had a felony, he could have potentially gotten connected to involuntary treatment for his mental health issues and things like that,” Robbins said. “It’s more difficult sometimes to connect patients who are too acute for voluntary programs to the care that they need outside of the criminal justice system.”

For a dozen years before she was hired by the city, and now in her current job, she said families have reached out for help when misdemeanor-level misbehavior generates a sort of endless loop, forcing distraught loved ones to watch a family member cycle between the courts and the streets.

“It’s not everyone, but it is a theme that I’ve noticed,” Robbins said, adding that she was aware of two similar situations in local courts just last week.

It is difficult to discern just how common Ed’s situation is. Official statistics appear elusive. But San Diego County’s experience with CARE Court, which started locally in October 2023, has had a high rate of petition rejections.

According to the county’s behavioral health department, 261 of 445 petitions have been rejected over the past two years. According to county records, 71 of those 261 ended as a result of the subject of a CARE Court petition refusing to participate.

With 24 graduates to date, and 105 people currently participating in CARE Court-directed treatment, San Diego is a frontrunner in implementing the program, but dreams of it reaching the 7,000 to 12,000 people estimated to qualify for treatment statewide have so far gone unrealized.

Jo is in the habit of keeping the blinds of her San Diego home closed at all times after cameras captured her son, Ed, repeatedly violating restraining orders in 2025. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Jo is in the habit of keeping the blinds of her San Diego home closed at all times after cameras captured her son, Ed, repeatedly violating restraining orders in 2025. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Dudas said she petitioned for Ed to participate in CARE Court twice this year, with his public defender offering it a third time during his most recent trial. She said he declined all three times. The state has also expanded its definition of grave disability, a condition that can lead to involuntary treatment if a person cannot meet their basic needs, such as food, shelter and personal safety. Dudas said that appealing on these grounds has also gone nowhere.

This year, she has continually received calls from her aunt, often huddled in her bathroom, while Ed prowls outside.

Jo agreed to discuss the situation provided that her and Ed’s full names remain unpublished. She’s homebound and in poor health and doesn’t want to jeopardize a fragile housing situation. And she still hopes that her son, who she says is transformed into a gentleman when he takes his medications, will someday find a way to sustain his cognitive equilibrium.

Until then, Ed’s history of violence leaves her feeling unsafe in her own home.

In 2011, she recalled, after he had been released from Patton State Hospital, seeming like a new man with the aid of long-acting psychiatric medication, she allowed him to resume living in her home. When the medication wore off, she said, he began self-medicating with hard drugs. She let him know that there could be no such activity in her home, and that’s when the trouble started.

“Around three o’clock in the morning, he came out, and he put his fist underneath my chin and told me to get out,” she said, adding that it looked like he had a knife in his hand.

That was the first time that circumstances forced her to seek a restraining order against her own son. Years later, she said, on one of his returns to her home, he explained why he kicked her out.

“He wanted to know why I wouldn’t let him in the house, and I told him, ‘because, you know, you put me out at three in the morning with nothing but my purse,’” she said. “And he said, ‘the voices were telling me to kill you, and I didn’t want to hurt you, so I was trying to protect you.’”

She does not wish to see her son suffer any loss of freedom.

“I hate to go through this with him because it’s no fun when your brain isn’t working, but I don’t know what else to do,” Jo said.

During his recent sentencing hearing, which came a week after a jury convicted him on 10 misdemeanor counts of restraining order violations, Judge Brower did heed the request of a deputy city attorney, ordering that Ed be offered participation in the county’s In Home Outreach Team and Assisted Outpatient Treatment programs. But the judge noted that both programs are voluntary. The San Diego County Sheriff’s Office said in an email that it cannot comment on any specific patient’s case but confirmed that NaphCare, its in-house medical provider, does “initiate conservatorship referrals regularly.”

It was clear in court last month that Ed does not believe he is ill. Speaking on his own behalf before sentencing, he insisted that he had faced a “federal Supreme Court lawsuit about wrongful entrapment,” that he only revisited her home constantly to check his mail, wouldn’t be homeless if he could just access his bank account, had recently been reinstated in the Air Force, that Jo is not his mother and that his name is not the one that has appeared on court documents.

The judge did issue a new restraining order, stating that Ed “does present a danger” to Jo’s safety.

June Dudas testifies in San Diego County Superior Court, Nov. 10, 2025 in San Diego, Calif. (Denis Poroy / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

June Dudas testifies in San Diego County Superior Court, Nov. 10, 2025 in San Diego, Calif. (Denis Poroy / For The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Civil and disability rights advocacy groups have argued forcefully against increasing rates of conservatorship, asserting that taking away a person’s rights is often unnecessary and unjust. Disability Rights California, a nonprofit that has been among the strongest critics, declined to comment on Ed’s situation directly, but did emphasize that voluntary treatment is its gold standard.

“We support approaches that emphasize voluntary treatment and community-based supports, as these are proven to be more effective and respectful of personal autonomy,” the organization said in an email. “While we cannot comment on the specifics of this individual’s case, we believe that systemic solutions, such as improved access to comprehensive services, housing and early intervention, are critical to reducing situations like this.”

But for Dudas, and many with family members who do not realize or accept that they are suffering from mental illnesses, that concern for rights can seem one-sided.

“I’m going to appreciate the days that I don’t have to pay attention to the Ring cameras,” she said. “But I know, at the end of that, that’s exactly where we’re going to be again, and then I’m going to have to start the process all over again and talk to all of these people all over again and try to get them engaged all over again. I mean, it just sounds like hell.”

And the court record makes it starkly clear that many have tried and failed to help Ed through involuntary means.

An appellate court decision filed in 2024 by his attorney to challenge a technical detail of a six-year prison sentence for striking a stranger in the face and breaking her nose in 2020 lays out his history of run-ins with the law. The document says that he had been committed to Patton State Hospital in 2013 and 2017 and again in 2021 to have his competency to stand trial restored.

Appellate judges referenced his long history of struggle with mental illness in their ruling, agreeing with a trial court’s decision that Ed “presents a serious danger to others.”

Judges wrote that his “criminal history spans three decades. Many of his convictions involve violence or serious risk of violence, including driving under the influence, burglary, exhibiting a firearm to resist arrest, disturbing the peace, elder abuse, and aggravated assault. When placed on probation in 2014, he failed to remain law-abiding and was ultimately sentenced to prison.”

In refusing the requests of his attorney on appeal, judges noted that Ed was “on probation when he committed the underlying violent crime. He was also armed with a knife; he committed to the underlying offense without provocation, and he has expressed no remorse. Most recently, his medication compliance in jail was characterized by ‘multiple medication refusals.’”

This progression, said Karen Larsen, chief executive officer of the Steinberg Institute, a nonprofit that conducts mental health policy research and advocacy, seems to argue for conservancy. Current law, she said, allows psychiatrists working in jails to refer an inmate for consideration of conservatorship.

“This individual is the perfect candidate for conservatorship,” Larsen said. “If CARE Court’s not an option, you’re supposed to go to the next step, which is conservatorship.”

Generally, involuntary treatment still occurs through a state law triggered by a 911 call that causes a bystander to believe that a person is a danger to themselves or others or gravely disabled.

Urmi Patel, deputy director of the county’s Behavioral Health Service’s Healthcare Oversight Unit, declined to comment on Ed’s situation, noting that health care privacy law prevents providers of mental health care from discussing specific patients.

Speaking generally, she said that the county strives to make sure that services are provided in the least restrictive manner possible.

The litmus test for conservancy, she said, is grave disability.

“Whether or not somebody has a criminal history in jail or has charges or is on probation, all of that may be a part of their, let’s say, their packet that’s put together, but they still have to meet that criteria of grave disability in order for us to even be able to do the (temporary conservatorship),” Patel said.

A security camera on a porch on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2025 in San Diego, CA. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

A security camera on a porch on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2025 in San Diego, CA. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

But Dudas says she has had trouble, across three misdemeanor arrests this year, getting anyone to order the evaluation that could lead to conservatorship, even though her cousin, she said, has been living on the streets in between his arrests, suggesting that, at the very least, he is unable to provide for consistent shelter.

Dudas said that she requested such an evaluation under section 5200 of the state Welfare and Institutions Code in September, but was told such an evaluation was outside the court’s purview. Section 5200 has been on the books for many decades, predating the state’s current involuntary treatment law, the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which the Legislature enacted in 1967.

Dr. Aaron Meyer, a psychiatrist with UC San Diego Health who has been active in the public discourse on voluntary versus involuntary treatment, said that this law can provide a pathway for family members, though it does not appear to get far in San Diego County.

“For families who have repeatedly been asking for a 5150 hold and seeing their loved ones deteriorate or end up in jail, section 5200 offers an alternative avenue to mental health treatment for people who are unable or unwilling to access care and are at risk of deterioration or represent a danger to themselves or others,” Meyer said.

The psychiatrist, who did not comment directly on Ed’s case, said that as far as he is aware, public requests for a mental health evaluation of an individual under section 5200 end up in the normal flow of emergency calls.

“My understanding is that when you contact the conservator’s office, they would direct you to call 911 for consideration of a 5150,” Meyer said, referring to the section of state law that allows detention of individuals thought to possibly be a danger to themselves or others or gravely disabled.

That route, Meyer said, can be difficult in complicated cases, especially when families are trying to communicate a pattern of behavior.

“Families can have a great understanding of an individual’s time course that can’t really be reflected in three lines on a 5150 form,” Meyer said, adding that San Bernardino County appeared to allow direct 5200 complaints.

A county spokesperson did not confirm Meyer’s assertion that public requests for evaluation under section 5200 are referred to emergency dispatch. Informal conversation with behavioral health directors in other counties, the county said, have not turned up other locations where this section of the law is handled differently.

Patel said that the county relies on psychiatric emergency and mobile crisis response teams to handle public concerns about emergent symptoms of mental illness. These resources, Patel said, are designed to deliver a comprehensive response.

“The PERT team and MCRT allow us as a county to have the infrastructure and the procedures in place that if somebody was assessed and the hold was appropriate, that we didn’t have to scramble to figure out how to get that person to an actual facility,” Patel said.

But there are efforts underway to make the connections between the courts and behavioral health departments more robust. Senate Bill 27, a new piece of legislation signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in October, expands the list of mental illnesses that qualify for CARE Court to include bipolar disorder with psychotic features. And the law also requires “jail medical providers to share confidential medical records and other relevant information with the court for the purpose of determining (the) likelihood of eligibility for behavioral health services and programs.”

An announcement makes it clear that misdemeanors are on the Legislature’s radar, noting that SB27 requires “judges to consider CARE as a frontline option for misdemeanor defendants with serious mental illness. Many of these individuals cycle through the criminal justice system for years, as, once they exit jail-based treatment, they lack reliable access to mental health care, stable housing, and other necessary supportive services.”

“We have already started receiving referrals from the court to essentially find an alternate pathway for individuals who are going into the court system,” Patel said.

But participation in CARE Court remains voluntary. There is a growing effort in the Legislature to broaden the set of experts able to request conservancy. Senate Bill 367, introduced by Sen. Benjamin Allen, D-Santa Monica, and co-sponsored by Sen. Catherine Blakespear of Encinitas, would expand the list of individuals who can recommend conservatorship and would also make changes to the facts considered in conservatorship proceedings, according to the state legislative analyst’s office.

A shelving unit blocks a window to increase security during frequent visits from Jo’s son. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

A shelving unit blocks a window to increase security during frequent visits from Jo’s son. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

For her part, Jo says she is prepared to begin calling her niece again next year if Ed is released. Sitting in her living room, she said that the plan will be the same as it has been, locking herself in the bathroom until law enforcement arrives. She does not call 911 herself, she said, because she does not want Ed to hear her.

“The reason I hide out in the bathroom is because, one time a couple of years ago, he threatened to smash in the front windows and get in,” she said. “That’s why I get out of here. Just in case.”