For more than a century, the modern university has been sustained by a shared assumption: that a degree is the most reliable gateway into skilled employment.

Employers have sifted job applicants primarily on the basis of their degree outcomes, and students have planned their lives – and their finances – around this expectation. Governments have funded institutions on the basis that higher learning produces productive citizens and economic growth.

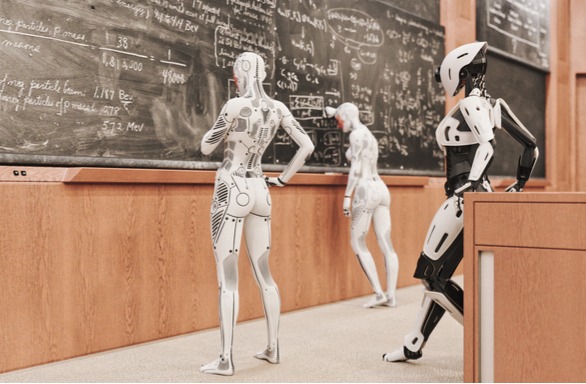

Artificial intelligence (AI) challenges that settlement by enabling employers to reconsider how they evaluate skill, train staff and structure work itself. We are not merely seeing a shift in pedagogy. We are seeing a shift in the labour market that has the potential to render the degree less central to economic life than at any point since mass higher education began.

The question is no longer whether universities should respond to AI. They already are, and mostly in predictable ways: overhauling exams and tightening academic integrity rules, integrating new technologies into curricula. The deeper issue is whether the link between higher education and employment is weakening, and how quickly that weakening could translate into lasting structural change within higher education.

That change has already begun. Over the past five years, major employers in technology, finance, media and design have already reduced degree requirements or replaced them with internal competency assessments. Tech giants such as Apple, IBM and Google, alongside several global consultancies, have already eliminated degree mandates for many technical and creative positions.

These decisions have typically been explained simply as an attempt to widen the talent pool. In reality, they signal something more consequential: employers are increasingly confident that they can identify and develop talent without outsourcing the task to universities. If generative AI continues to accelerate skills acquisition, job-specific training and performance evaluation, this confidence could become the norm rather than the exception.

Not all degrees will lose value at the same time. Rather, the landscape will fracture unevenly, depending on how tightly an associated profession is regulated and how easily its core competencies can be measured or replicated with AI. Fields that require formal licensure, such as medicine, pharmacy, law and engineering, are likely to remain dependent on accredited training pathways, at least in the medium term.

In contrast, sectors where skill can be demonstrated through portfolios, performance tests or rapid project-based assessment are positioned to shift earliest. Software development, marketing, design, data analysis and parts of finance increasingly reward demonstrable ability over formal qualification. Generative AI tools lower the time and cost required to produce credible outputs, meaning candidates can evidence capability faster and outside institutional settings. If a 19-year-old can demonstrate professional-grade work within months using AI-augmented workflows offered by private training providers and certification platforms, the degree begins to look like a slower and less direct route to employability.

Indeed, if AI rapidly improves at evaluating real-time performance, employers far beyond the tech sector may conclude that they themselves can train, assess and credential employees more effectively than universities and without excessive cost. In such a scenario, the degree’s value – especially to the students and governments that have to bear its costs – erodes quickly and visibly, especially in industries already struggling with graduate oversupply.

These shifts will not be uniform, and there will be no single moment of collapse. Rather, it will play out like a pattern of quiet withdrawal: employers will stop insisting, students will stop assuming and universities will get ever smaller as enrolment dwindles.

The key uncertainty is pace. One view is that degrees – especially those from elite institutions – can persist, albeit with declining relevance, for decades. The university sector tends to assume slow change because its own structures evolve slowly. But employers are not bound to those timelines, and their calculations are economic rather than cultural. If the supply of capable workers increases through AI-augmented upskilling outside formal education, continuing to demand a degree starts to look less like assuring quality and more like defending a credential for its own sake.

The core strategic question is whether universities see themselves primarily as providers of foundational intellectual formation or as gatekeepers to employment. If the former, they must articulate that purpose clearly and defend it on its own terms. If the latter, they must demonstrate that their training is materially better than faster, cheaper, AI-supported alternatives.

Different universities may take different views on that strategic question, but none of them can avoid it. No university can rely on historical prestige to carry its historical credentials indefinitely.

Those that acknowledge this early will adapt. Those that do not may find that the ground has shifted beneath them while they were still debating assessment policies.

Ali Hindi is a lecturer in pharmacy practice at the University of Manchester.