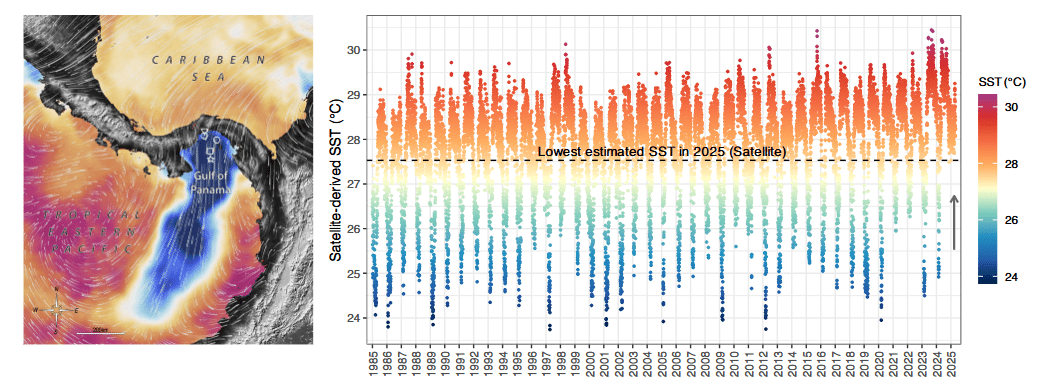

An equatorial ocean system long considered stable has abruptly failed. For the first time in at least four decades, the Pacific upwelling off Panama—a critical process that brings nutrient-rich deep water to the surface—did not occur during its expected season in early 2025.

The shutdown of this upwelling cycle, revealed through long-term satellite data and direct field measurements, has left tropical waters warmer, less productive, and dangerously imbalanced. It’s a development researchers are calling both unprecedented and deeply concerning.

New findings published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences detail what may be an early signal of larger climate-related instabilities in tropical oceans, ecosystems that support major fisheries and coral reef systems across the globe.

A Key Ocean Engine Goes Silent

Each year between January and April, strong trade winds blowing across the isthmus of Panama create ideal conditions for upwelling in the Gulf of Panama. As surface waters are pushed offshore, cooler, nutrient-dense water from deeper layers rises to replace it. This process fuels phytoplankton growth, bolsters coastal fisheries, and cools coral reef ecosystems, helping them survive seasonal thermal stress.

But in 2025, that entire system stalled. Satellite records showed little to no chlorophyll presence in the water—a stark indicator of diminished biological productivity. Sea surface temperatures remained abnormally high, dipping below 25°C only briefly in early March, roughly six weeks later than expected.

Researchers aboard the scientific research vessel Eugen Seibold confirmed the absence of vertical water mixing, with deeper cool waters staying trapped beneath a stratified surface layer.

Data spanning more than 40 years revealed that the timing, strength, and duration of this seasonal upwelling had never failed in this way. While previous La Niña events affected the system mildly, none had triggered a total collapse like what was recorded in 2025.

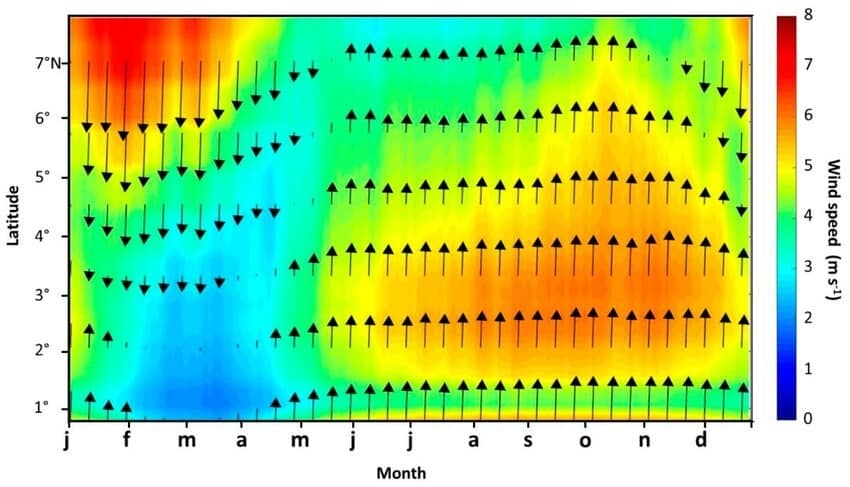

A Drop in Wind Frequency—Not Strength

The investigation pointed to a sharp decline in the frequency of Panama’s wind-jets—short-lived, powerful gusts that historically drive the upwelling process. The number of wind events fell by roughly 74% compared to previous decades. Importantly, wind speeds remained close to historic norms when they did occur, indicating that it was the lack of consistency, not force, that disrupted the system.

Researchers suspect the shift is linked to changes in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a key atmospheric feature whose northward movement during the 2024–2025 La Niña may have contributed to wind suppression. Still, the report notes that stronger ENSO cycles in the past failed to produce anything comparable, raising the possibility that underlying climate warming may be weakening these wind-driven systems in ways models have not fully captured.

The team behind the study includes scientists from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, and several global partners. Their conclusion is clear: tropical upwelling systems may be more vulnerable than previously believed.

Fisheries Shrink, Coral Reefs Overheat

The disappearance of upwelling triggered an immediate biological response. Phytoplankton levels plummeted, depriving the food web of its base. Populations of fish that rely on plankton—sardines, mackerel, and cephalopods—declined in coastal areas, disrupting fisheries that supply both commercial markets and local subsistence communities.

Without the seasonal cooling effect of deep ocean water, coral reefs experienced prolonged thermal exposure, increasing the severity of bleaching events in early 2025. Dissolved oxygen levels also dropped in the water column, compounding stress on benthic and deep-dwelling species.

These cascading effects underscore how a disruption in one physical process can trigger widespread ecological damage—particularly in tropical zones where marine systems are tightly linked to seasonal atmospheric conditions.

The Tropical Monitoring Gap

One of the most revealing aspects of the event is that it might have gone unnoticed without long-running ocean monitoring programs in the region. Unlike well-instrumented upwelling systems in temperate zones, tropical areas like the Gulf of Panama suffer from gaps in observational infrastructure.

This lack of visibility has consequences. Upwelling events, despite their role in carbon cycling, fisheries productivity, and climate regulation, receive limited attention in global climate models. If disruptions like this become more frequent, or begin occurring in other Eastern Tropical Pacific regions, researchers warn that climate impacts may unfold faster than anticipated, and with less warning.

The study’s authors advocate for expanded monitoring networks, improved modeling of wind-ocean interactions, and greater integration of tropical data into global systems. The future stability of entire marine ecosystems may depend on it.