Researchers have unveiled a startling discovery: not all atoms in a liquid are jostling around.

Some, it turns out, stay put, capable of corralling entire liquids into a bizarre, supercooled state.

According to researchers at the University of Nottingham and the University of Ulm in Germany, the unusual state of matter is expected to play a role in fields such as pharmaceuticals, aviation, construction, and electronics.

The mystery of motion

Matter is conventionally understood to exist in three states: gas, liquid, and solid.

While the orderly arrangement of solids and the chaotic freedom of gases are relatively well-described, liquids have always remained the most mysterious of the trio.

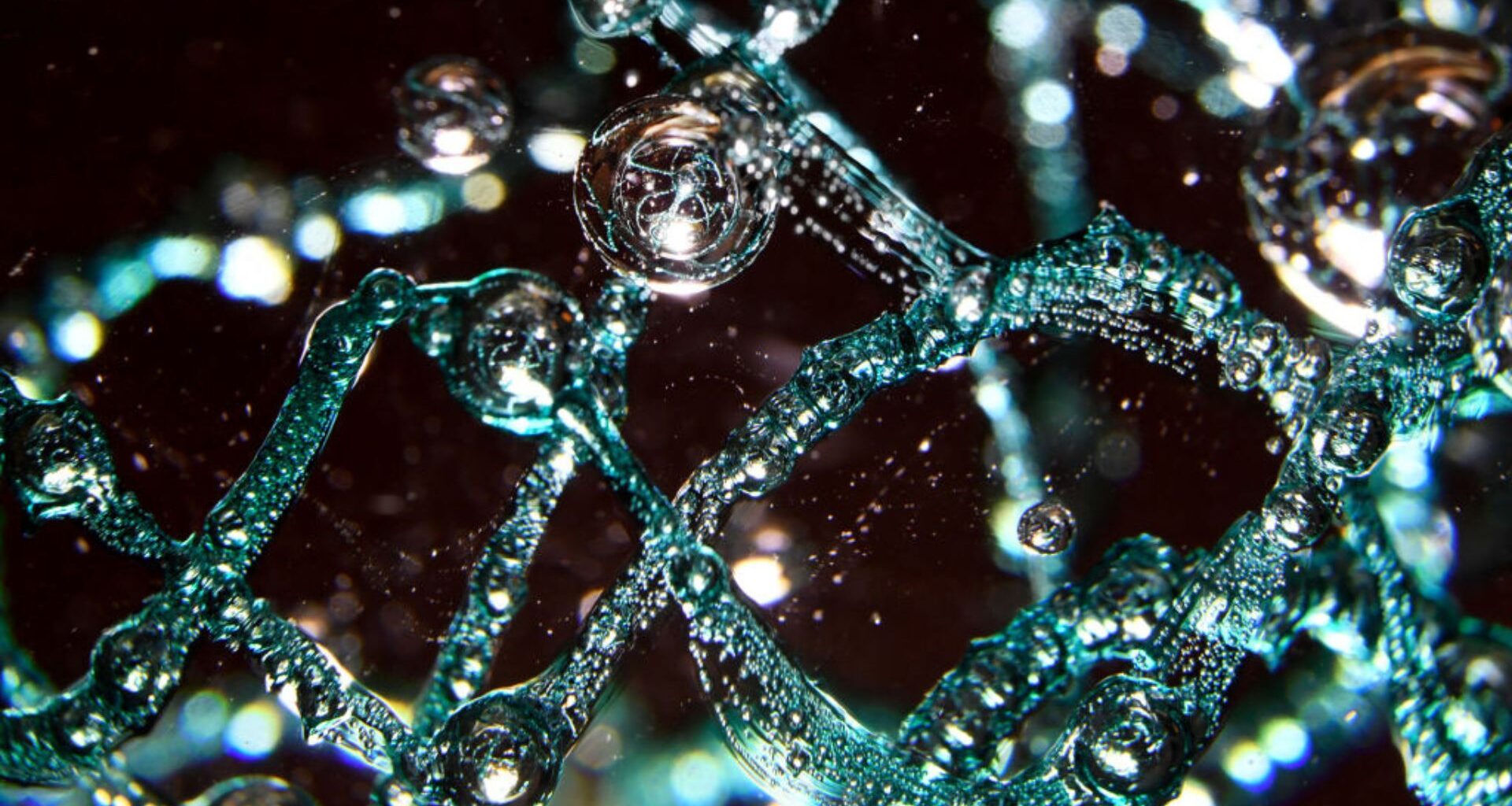

Atoms in a liquid constantly shift and rapidly interact, resembling a bustling crowd.

Particularly, the moment a liquid begins to solidify dictates the final structure and functional properties of the resulting solid. Solid formation is vital in processes ranging from mineralization and ice formation to the folding of protein fibrils.

To peek into this critical process, Dr. Christopher Leist used the unique low-voltage SALVE transmission electron microscope at Ulm.

“We began by melting metal nanoparticles, such as platinum, gold, and palladium, deposited on an atomically thin support—graphene. We used graphene as a sort of hob for this process to heat the particles, and as they melted, their atoms began to move rapidly, as expected. However, to our surprise, we found that some atoms remained stationary,” said Leist.

Even at very high temperatures, these static atoms remained firmly bonded to the point defects present on the graphene support.

The researchers used an electron beam to increase the number of defects, thereby achieving unprecedented control over the concentration of stationary atoms in the liquid metal.

The atomic corral and a new phase

This remarkable control allowed the team to discover how these pinned atoms influence solidification.

A normal crystal forms only when the number of stationary atoms remains small. But when the number is high, especially if they form a ring-like structure, the solidification is drastically disrupted. The liquid is trapped — or corralled — and can remain liquid far into the supercooled zone.

“The effect is particularly striking when stationary atoms create a ring that surrounds the liquid. Once the liquid is trapped in this atomic corral, it can remain in a liquid state even at temperatures significantly below its freezing point, which for platinum can be as low as 350 degrees Celsius—that is more than 1,000 degrees below what is typically expected,” noted Professor Andrei Khlobystov from the University of Nottingham.

When the corralled liquid finally solidifies, it does so as an amorphous solid — an unstable, glass-like form. Only when the atomic confinement is broken is the metal released to transform into its normal, stable crystalline structure.

The discovery of this hybrid metal state is a significant breakthrough. Previously, the concept of corralling — confining entities — had been demonstrated only for photons and electrons; this is the first time it has been achieved with atoms.

It could lead to the design of self-cleaning catalysts with improved activity and longevity. Ultimately, this work could herald a more efficient use of rare metals in clean technologies, such as energy conversion and storage.

The study was published in the journal ACS Nano.