Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are the heavyweight champions of cosmic fireworks – brief, blistering flashes of high-energy light that typically flare and vanish within seconds or minutes. They are so short-lived that catching one in action often feels like cosmic luck.

But on July 2, 2025, that script unraveled. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected a GRB that simply refused to stop, firing in repeating pulses for more than seven hours.

The event – now named GRB 250702B – immediately shattered duration records. It upended long-standing assumptions about how astronomers classify and explain these extreme explosions.

What followed was a global chase to pin down what could possibly power a burst this stubborn, this bright, and this long-lived.

Chasing the cosmic signal

Fermi caught the first salvo in gamma rays, while X-ray telescopes pinned down the sky position quickly enough to trigger a worldwide follow-up.

Infrared data from ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) delivered an early, crucial clue: the source sits in a galaxy beyond the Milky Way.

With the origin safely extragalactic, the race began to chart the event’s fading afterglow. This longer-lived light lingers after the initial blast subsides.

Capturing gamma-ray bursts

Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, led one of the most ambitious ground campaigns.

His team moved three of the world’s premier observatories into position: the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope in Chile and the twin 8.1-meter International Gemini Observatory telescopes in Hawai‘i and Chile.

Observations began roughly 15 hours after the trigger. They continued for about 18 days and captured a detailed light curve across near-infrared and optical wavelengths.

“The ability to rapidly point the Blanco and Gemini telescopes on short notice is crucial to capturing transient events such as gamma-ray bursts,” said Carney.

“Without this ability, we would be limited in our understanding of distant events in the dynamic night sky.”

GRB 250702B hidden by cosmic dust

The Blanco telescope’s NEWFIRM wide-field infrared camera and the 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera (DECam) worked with the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs (GMOS) to reveal a stubborn obstacle. GRB 250702B is heavily obscured by dust.

Interstellar dust in our own galaxy dims the view, but the dominant curtain appears to hang in the host galaxy itself.

In fact, Gemini North required nearly two hours of deep integration to coax out the faint, close-to-visible signature of the host beneath those dusty lanes.

That obscuration helps explain why the afterglow stubbornly refused to show up in standard visible-light filters while remaining accessible in the infrared.

A focused cosmic jet

To unravel the physics behind the record-breaker, Carney’s team folded in new Keck I observations and public data from the VLT and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, plus X-ray and radio measurements.

Confronting this multi-wavelength dataset with theoretical models points to a familiar engine with unfamiliar power: a narrow, relativistic jet – material accelerated to near light-speed – plowing into a dense environment.

The afterglow’s shape, color, and temporal evolution are consistent with a jet that stayed bright as it smashed into surrounding gas and dust, converting kinetic energy into a long, luminous fade.

The host galaxy itself appears unusually massive for a GRB site, and the line of sight passes through what is likely a thick dust lane. Together, those environmental clues offer rare constraints on the system that powered the initial outburst.

Singular gamma-ray burst

Since GRBs were recognized in 1973, astronomers have cataloged roughly 15,000 of them. Only a handful approach the duration of GRB 250702B.

Those outliers often trace to extreme scenarios: a blue supergiant’s collapse, a tidal disruption event (TDE) in which a star is torn apart by a massive black hole, or the spin-down of a newborn magnetar.

GRB 250702B doesn’t slide cleanly into any of those boxes. It belongs to the ultra-long tail of the duration distribution.

Yet its afterglow looks more jet-like than some known TDEs and more dust-enshrouded than typical collapses of massive stars.

Possible origins of GRB 250702B

At this stage, the data support several competing (and exciting) possibilities. One possibility involves an unusual stellar collapse. A black hole forms inside a hydrogen-stripped star, creating a helium-rich body ready to launch a long-lived jet.

Another possibility is a micro–tidal disruption event. In this scenario, a star or sub-stellar object – such as a planet or brown dwarf – is shredded during a close pass by a compact stellar remnant, lighting up a jet as the debris spirals inward.

The most tantalizing scenario points to an intermediate-mass black hole. This elusive object, weighing between roughly 10² and 10⁵ Suns, tears a star apart and produces a relativistic jet we can finally see.

If confirmed, that would mark the first direct sighting of such a jet from an intermediate-mass black hole in the act of feeding.

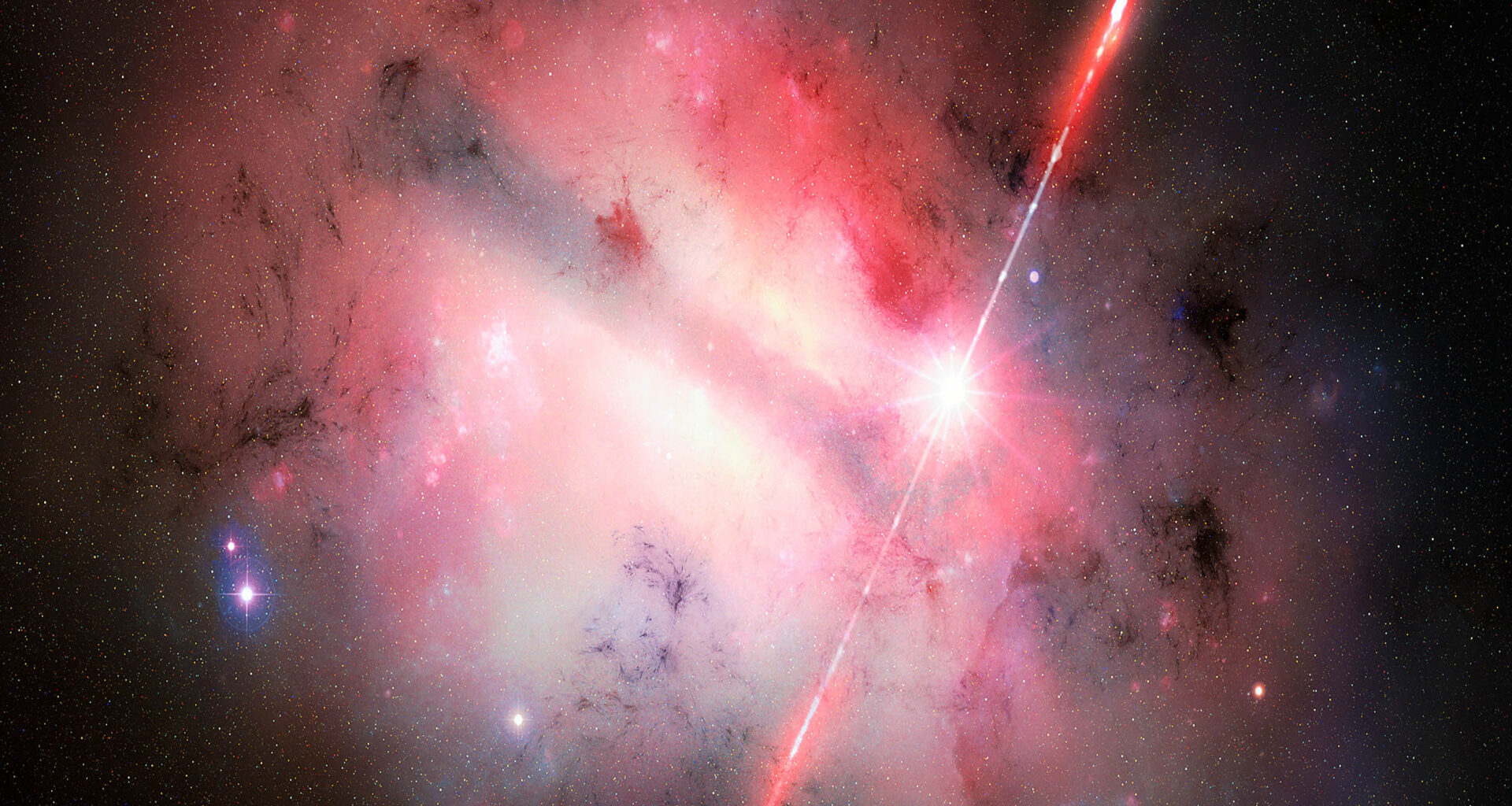

The stellar field around the host galaxy of GRB 250702B – the longest gamma-ray burst that astronomers have ever observed. Credit: NSF NOIRLab. Click image to enlarge.Why GRB 250702B matters

The stellar field around the host galaxy of GRB 250702B – the longest gamma-ray burst that astronomers have ever observed. Credit: NSF NOIRLab. Click image to enlarge.Why GRB 250702B matters

Ultra-long GRBs like 250702B are cosmic stress tests. They force models of jet production, energy extraction, and disk accretion to work not for seconds but for hours.

The heavy dust along the line of sight reminds observers that selection effects matter. Without infrared reach and persistent follow-up, events like this can hide in plain sight. And the unusually massive host galaxy widens the demographic map of where powerful jets can be born.

There’s also the broader puzzle of how many distinct pathways can lead to “GRB-like” behavior. Are we looking at one phenomenon with a wide parameter spread, or several engines that converge on similar observational signatures?

The relentless cadence of GRB 250702B puts fresh pressure on that question and offers a benchmark any theory must match.

Questions still remain

As the glow fades, the dig goes on. Late-time infrared imaging can search for a lingering supernova signature. Deep radio monitoring can trace the jet’s energy as it slows.

Spectroscopy can refine the host’s redshift and metallicity and test how dust and gas shape the view. And new alerts, especially those captured rapidly in the infrared, may reveal more cousins in this ultra-long family.

“This work presents a fascinating cosmic archaeology problem in which we’re reconstructing an event that occurred billions of light-years away,” Carney said.

“The uncovering of these cosmic mysteries demonstrates how much we are still learning about the universe’s most extreme events. It reminds us to keep imagining what might be happening out there.”

The study is published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–