New measurements by astronomers have strengthened the Hubble tension, a discrepancy between the early expansion rate of the universe compared with closer, more recent astronomical observations.

Based on existing physical models, scientists expected that the universe would have consistently expanded at a steady rate, as characterized by the Hubble constant. Yet, a new paper published in Astronomy and Astrophysics confirms a discrepancy, correlating observations from the W. M. Keck Observatory, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Very Large Telescope, which show the rate of expansion appears to be shifting over time.

“What many scientists are hoping is that this may be the beginning of a new cosmological model,” said co-author Tommaso Treu, Distinguished Professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“This is the dream of every physicist,” said co-author Simon Birrer, Assistant Professor of Physics at Stony Brook University. “Find something wrong in our understanding so we can discover something new and profound.”

Confirming the Hubble Tension

Astronomer Edwin Hubble made many significant contributions to astronomy, including what is known as the Hubble Constant, which bears his name. For this, Hubble first calculated the rate of universal expansion in 1929. From this figure, scientists can infer the universe’s age and history, providing crucial insights into what has occurred since the Big Bang.

However, new data now calls the Hubble constant into question, with one source—rather ironically—being the Hubble Space Telescope, which also bears the late astronomer’s name.

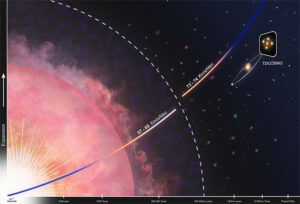

While the Hubble Tension calls into question the very nature of the Hubble Constant, the constant’s exact value has been open to revision for the past century. Astronomers have attempted to determine the correct figure by examining the present-day universe or by measuring data from very distant objects whose signatures take an immense amount of time to reach Earth, offering a window into a much younger universe.

Based on contemporary astronomical measurements, observations from the local universe yield an expansion rate of about 73 km/s/Mpc, whereas the distant early universe yields a rate of about 67 km/s/Mpc; a significant discrepancy.

There are significant ramifications to confirming the Hubble Tension, as researchers will have to devise and test explanations for what phenomena could be giving rise to the differing universal expansion rates. For instance, early dark energy may have increased the rate of expansion, or entirely new particles could be responsible for the measurements.

“This is significant in that cosmology as we know it may be broken,” commented John O’Meara, Chief Scientist and Deputy Director of Keck Observatory, in a Keck press release on the findings. “If it is true that the Hubble Tension isn’t a mistake in the measurements, we will have to come up with new physics.”

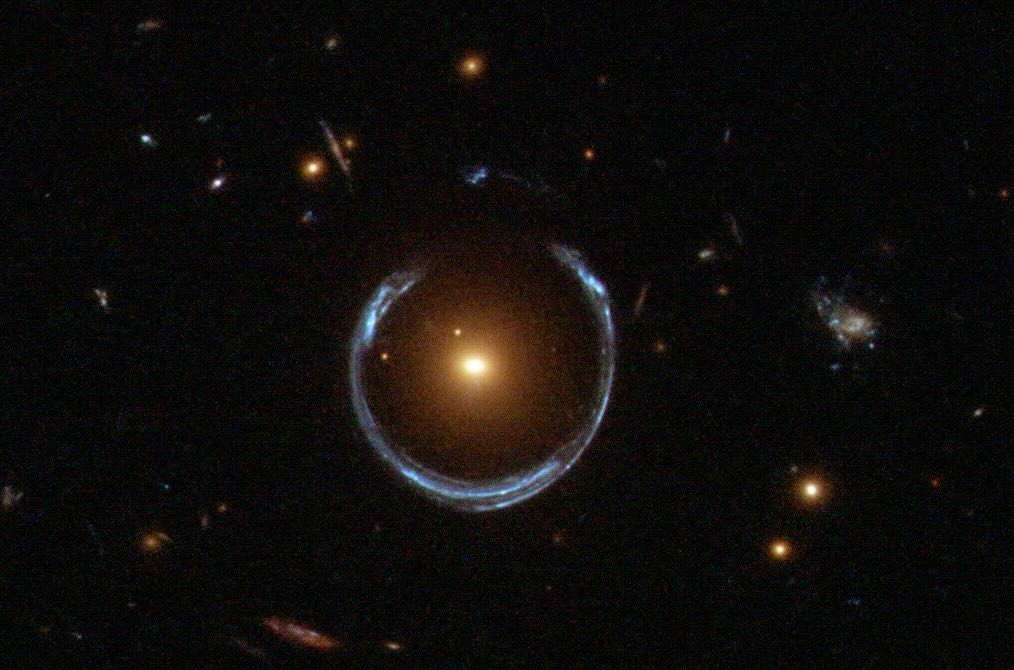

Researchers used gravitational lensing to apply time-delay cosmography, resulting in their confirmation of the Hubble tension. Credit: W. M. Keck Observatory / Adam Makarenko

Researchers used gravitational lensing to apply time-delay cosmography, resulting in their confirmation of the Hubble tension. Credit: W. M. Keck Observatory / Adam Makarenko

Gravitational Lensing

The new measurement supporting the Hubble Tension comes from a technique known as time-delay cosmography, which uses the light-distorting properties of gravitational lensing in galaxies and quasars to produce multiple images of a single object. As the brightness of objects changes over time, researchers can measure the delay between fluctuations across images to calculate an object’s distance from Earth and, from that data, determine how fast the universe is expanding.

“The key breakthrough relied on the motion of stars in the lens galaxies as measured via Keck/JWST/VLT spectroscopy to address the main source of uncertainty, known as the mass-sheet degeneracy,” said co-author Anowar Shajib, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago. “The result also relies on long-term collaborative work between observatories including time delay measurements from 20 years of photometric data obtained at ESO in Chile.”

The new work achieves an impressive 4.5% precision, but to establish the results beyond a reasonable doubt, further confirmation will be required to improve this figure to 1.5%. Whatever the case, scientists caution that accepting the Hubble Tension as accurate would require a fundamental rethinking of physics; therefore, additional cross-checking is necessary to confirm the results.

The paper, “TDCOSMO 2025: Cosmological Constraints from Strong Lensing Time Delays,” appeared in Astronomy and Astrophysics on December 5, 2025.

Ryan Whalen covers science and technology for The Debrief. He holds an MA in History and a Master of Library and Information Science with a certificate in Data Science. He can be contacted at ryan@thedebrief.org, and follow him on Twitter @mdntwvlf.