Astronomers have uncovered a rare exoplanet, HD 143811 AB b, that orbits two parent stars, mirroring the twin-sun system of Tatooine from Star Wars. This planet, however, presents an intriguing mystery: despite its proximity to its stars, it takes an astonishing 300 years to complete a single orbit.

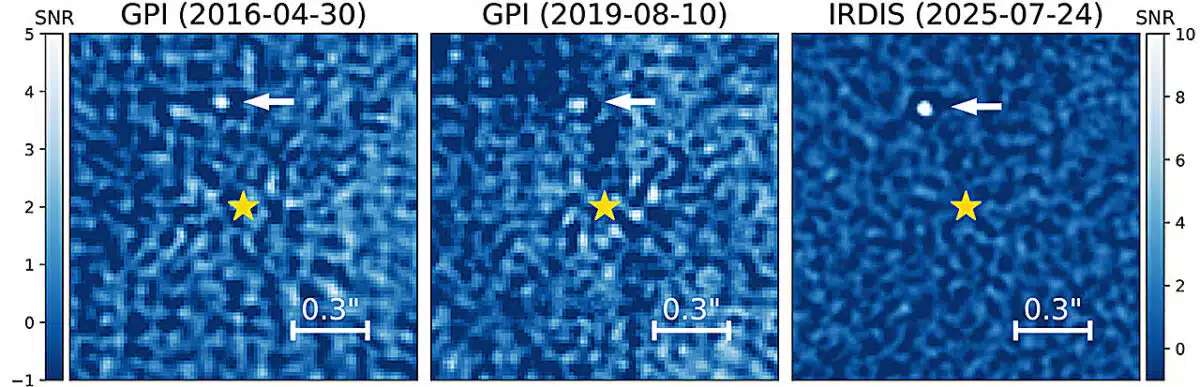

The planet was first captured in images taken by the Gemini South telescope in 2016, but it wasn’t until recent reanalysis of the data that astronomers realized the significance of the find. HD 143811 AB b’s orbital period is far longer than expected for a planet located relatively close to its parent stars. This unusual characteristic raises new questions about the formation and behavior of planets in binary systems, which are still not fully understood.

A Hidden Gem in Archived Data

The discovery of HD 143811 AB b, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, wasn’t the result of a new observation. Instead, astronomers revisited decade-old data collected by the Gemini South telescope’s Gemini Planet Imager (GPI). Between 2014 and 2022, GPI captured images of exoplanets by blocking out the glare of their parent stars using a coronagraph, a technique that allowed astronomers to see faint planets orbiting bright stars. While hundreds of stars were observed, only a few exoplanets were detected.

Jason Wang, an exoplanet imaging expert at Northwestern University, revisited the archival data as part of preparations for the GPI’s upcoming upgrade to GPI 2.0.

“I didn’t think we’d find any new planets,” Wang explained. “But I thought we should do our due diligence and check carefully anyway.”

His persistence paid off when the team noticed a faint object moving in tandem with a star. After cross-referencing the data with additional observations from the W.M. Keck Observatory, the object was confirmed as HD 143811 AB b, a planet that had been overlooked in previous analyses.

🚨: The REAL Star Wars planet! Scientists spot a Tatooine-like world orbiting two suns

Located 446 light-years from Earth, the planet, dubbed ‘HD 143811 b’, orbits a ‘binary system’ where two stars swirl around a central point. pic.twitter.com/rwJpJH4nE1

— All day Astronomy (@forallcurious) December 12, 2025

The Strange 300-Year Orbit

The planet, which is about six times the size of Jupiter, orbits its parent stars every 300 Earth years. Despite being much closer to its stars than most known exoplanets in binary systems—about six times closer—this planet takes far longer to complete an orbit than expected.

The two stars that the planet orbits are themselves relatively close, completing an orbit around each other every 18 Earth days. Yet, HD 143811 AB b’s orbit remains extraordinarily long. According to Wang, the planet’s long orbital period is “still uncertain” in terms of how it fits into our current understanding of planetary dynamics.

A time-lapse capture of exoplanet HD 143811 AB b as it revolves around its twin stars. Credit: Jason Wang/Northwestern University

A time-lapse capture of exoplanet HD 143811 AB b as it revolves around its twin stars. Credit: Jason Wang/Northwestern University

Tatooine-like Planets in Binary Star Systems

Binary stars are not uncommon, but planets that form around two stars are rare. Most known exoplanets are found around single stars, making the dynamics of planets in binary systems more difficult to study. In the case of HD 143811 AB b, the planet’s relatively young age—only about 13 million years—suggests it retains some heat from its formation. This makes the planet an interesting subject for studying planetary evolution. Nathalie Jones, a researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA), noted:

“We want to track the planet and monitor its orbit, as well as the orbit of the binary stars, so we can learn more about the interactions between binary stars and planets.”

The upgrade of GPI to its next iteration, GPI 2.0, will help astronomers gather even more precise data, potentially answering some of the lingering questions about how planets like HD 143811 AB b come to be.

The image scale is located in the bottom right corner, and an arrow marks the planet’s position. The color bar on the left refers to the two GPI maps. Credit: Astronomy & Astrophysics

The image scale is located in the bottom right corner, and an arrow marks the planet’s position. The color bar on the left refers to the two GPI maps. Credit: Astronomy & Astrophysics