Scientists have discovered a hidden RNA ‘switch’ used by bacteriophages to hijack bacterial cells, revealing a new layer of viral control that could help advance phage therapy and efforts to combat antibiotic-resistant infections.

Scientists at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have found a previously unknown way that viruses infecting bacteria take control of their hosts. They discovered a tiny RNA molecule that acts as a molecular ‘switch’ to speed up infection, providing key insights on phage biology that could support future efforts to develop alternatives to antibiotics.

The study focused on bacteriophages – viruses that infect bacteria – and revealed an unexpected regulatory role for a small RNA molecule called PreS. The findings demonstrate that phages can manipulate bacterial cells not only through proteins, but also by using RNA to reprogramme the cell from within.

A new layer of viral control

The research team, led by Dr Sahar Melamed at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem alongside PhD student Aviezer Silverman, MSc student Raneem Nashef and computational biologist Reut Wasserman, worked in collaboration with Professor Ido Golding from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

This study shows that RNA molecules can also play a central role, providing phages with a fast and flexible way to reshape the host cell during infection.

Their work shows that the phage produces PreS shortly after infection. This small RNA acts as a regulatory switch, altering how bacterial genes are translated into proteins after the bacterial genetic messages have already been made.

Until now, most phage research has concentrated on viral proteins. This study shows that RNA molecules can also play a central role, providing phages with a fast and flexible way to reshape the host cell during infection.

Hijacking DNA replication

Using advanced RNA-interaction mapping techniques known as RIL-seq, the researchers identified a key target of PreS: the bacterial messenger RNA that produces DnaN, an essential protein involved in DNA replication.

Using advanced RNA-interaction mapping techniques known as RIL-seq, the researchers identified a key target of PreS.

Under normal conditions, part of the dnaN message folds into a shape that limits access by ribosomes, the cell’s protein-making machinery. PreS binds to this folded region and changes its structure, allowing ribosomes to translate the message more efficiently.

The result is increased production of DnaN, enabling the virus to replicate its own DNA quicker and push the infection forward. When PreS was removed or its binding site disrupted, the phage replicated more slowly, and its destructive phase was delayed.

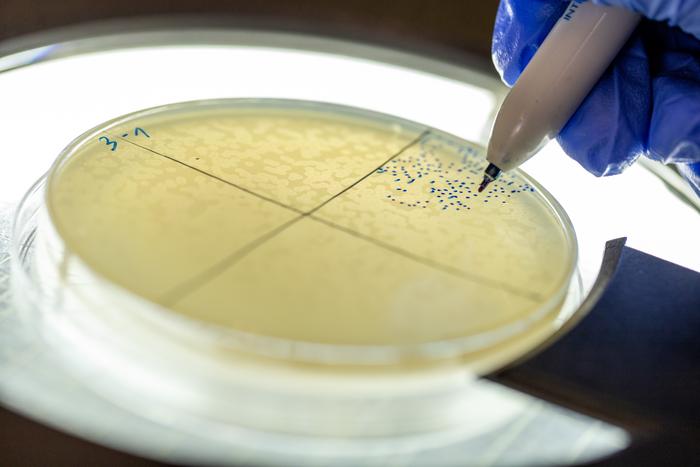

Plaques formed by phage lambda on an E. coli culture are being counted by Adi Levkowitz. Credit: Yosef Adest.

Rethinking a classic virus

The discovery is particularly important because it involves phage lambda, one of the most extensively studied viruses in biology. Despite decades of research, the virus was found to contain an entirely unexpected regulatory mechanism.

The discovery is particularly important because it involves phage lambda, one of the most extensively studied viruses in biology.

“This small RNA gives the phage another layer of control,” says Dr Sahar Melamed. “By regulating essential bacterial genes at exactly the right moment, the virus improves its chances of successful replication. What astonished us most is that phage lambda, one of the most intensively studied viruses for more than 75 years, still hides secrets. Discovering an unexpected RNA regulator in such a classic system suggests we have only grasped a single thread of what may be an entirely richer, more intricate tapestry of RNA-mediated control in phages.”

The researchers also found that PreS is conserved across many related phages, suggesting that small RNAs may represent a shared and largely unexplored viral toolkit.

Implications for antibiotic resistance

The findings come amid a rise in antibiotic resistance, which is projected to cause millions of deaths annually by mid-century if new treatments are not developed. Phage therapy – the use of viruses to selectively kill bacteria – is increasingly seen as a promising alternative.

While the study is basic, preclinical research, understanding how phages precisely control bacterial cells could help scientists engineer safer, more predictable and more effective phage-based treatments in the future.

By discovering the power of even the smallest viral molecules, the research opens up new possibilities in the fight against drug-resistant infections.