From his forthcoming book Cinematography Beyond Technique, MZed educator Tal Lazar shows how a story-first approach keeps filmmakers in charge when working with AI filmmaking. We also have Tal as our guest on this week’s podcast – our holiday episode – to talk about his book. So make sure not to miss it, it was a very though-provoking discussion on the future of cinematography – Nino

I used to open my cinematography course with a warning. Becoming a professional cinematographer, I said, demands the same discipline as becoming a concert pianist: if you don’t master the technique, you won’t be able to express yourself through music. For filmmakers, using cameras, lenses, and lamps should feel like second nature too since it will free them to focus on the story instead of the tools. 15 years and hundreds of students later, the way I teach cinematography has fundamentally changed. Whether I’m teaching undergraduate students at the City College of New York or experienced filmmakers on Sundance Institute’s Collab, I now open my first class with Berthe Morisot’s The Reading.

Berthe Morisot’s The Reading.

Berthe Morisot’s The Reading.

When I show the painting, I ask one question: if you had to choose a single main character, who would it be? The young woman in white or her mother in black? The answer reveals that our role as visual storytellers is not just to tell stories with images, but to make sure the entire audience understands it the same way. Year after year, we prove that it’s possible—almost everyone points to the woman in white as the main character. But when I ask students if they could put two figures in a wide shot and make one unmistakably the hero, even experienced Sundance filmmakers hesitate. That, I tell students, is what cinematographers do, and that is what we’ll learn.

Why intention matters more than skill

I still believe filmmakers should master technique the same way a concert pianist controls their instrument, but I no longer think that technical skill alone determines the strength of their work. There’s something else filmmakers need, and it may be the very thing that keeps them working in the age of AI. To uncover this hidden element in our work, I show students a second image that feels a bit like Morisot’s The Reading—but this one was created using Midjourney, an AI image generating program.

Midjourney’s interpretation of “The Reading”.

Midjourney’s interpretation of “The Reading”.

When I first prompted Midjourney to create this image, I quickly realized that just asking it to place two characters side by side gave it too much freedom. The images generated didn’t establish one character as the protagonist the way Morisot’s painting does. I had to revise my prompt to explain how to direct the viewer’s attention through the character’s placement and behavior, as well as lighting and framing. The final image works because I had an intention, and could articulate how to achieve it—and that’s exactly what cinematographers do on set every day. Their value to a film is not rooted in their ability to operate equipment, but in their ability to translate a director’s intention to visual language. This has been true long before AI, and it’s even more true now.

Is AI filmmaking considered cheating?

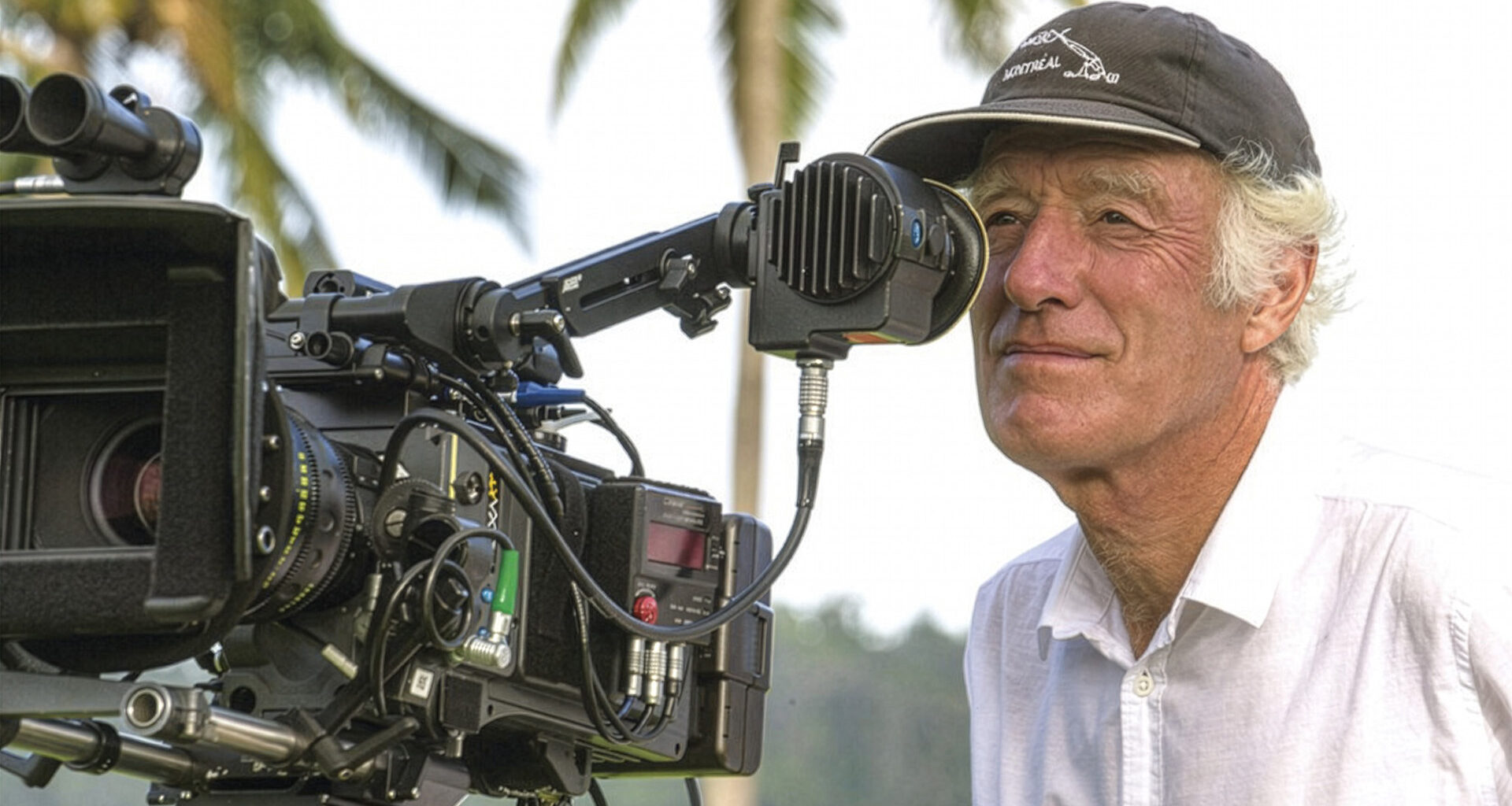

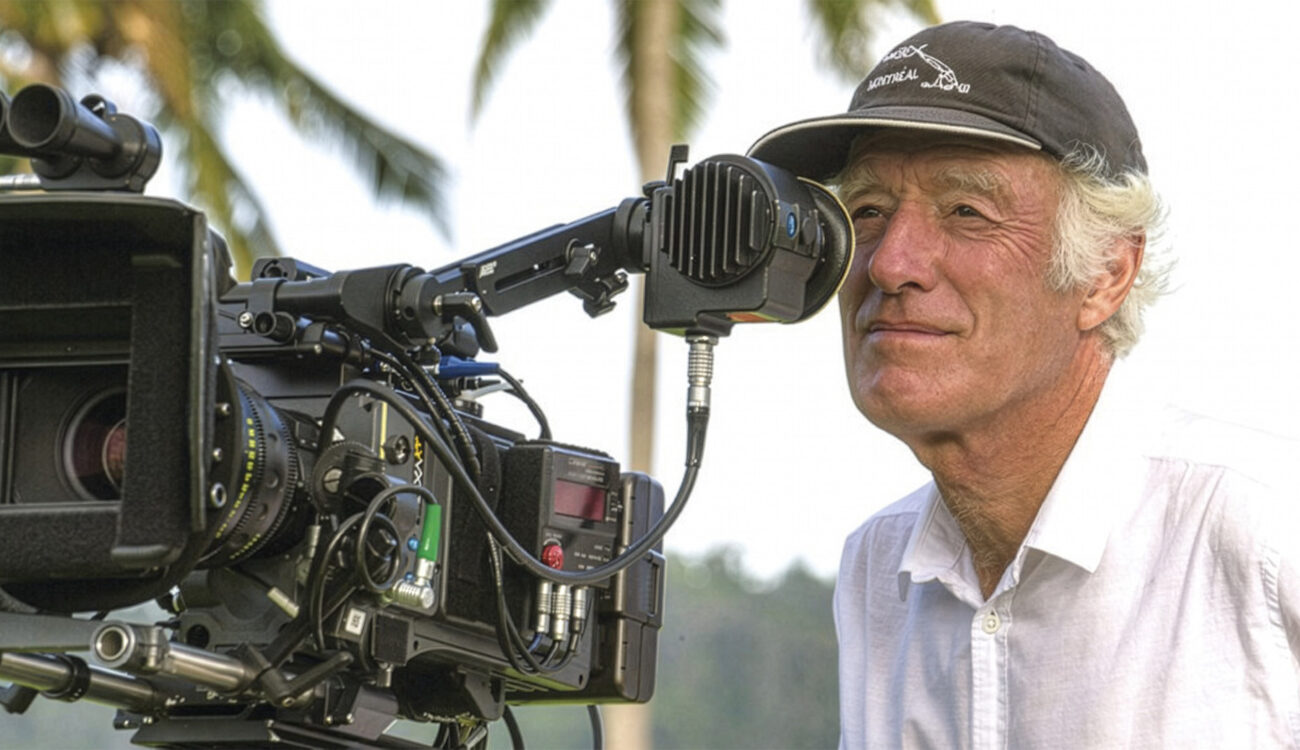

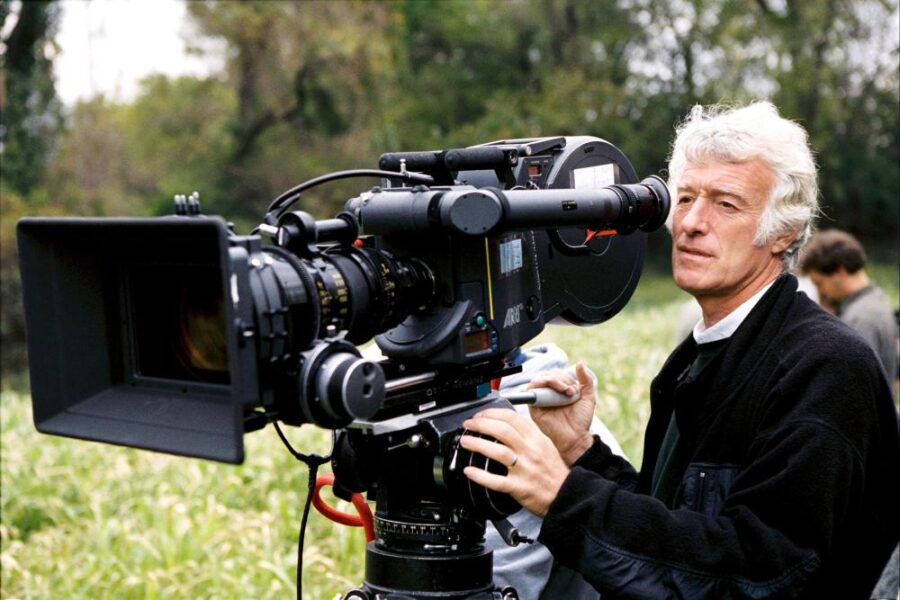

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC recently said: “I don’t believe AI is cheating if you have a reason for making a film with it, and a decent story and something to say. I don’t care what you use.” It’s rare for cinematographers to find Deakins’s words controversial—his statements are often treated like gospel. But this time filmmakers pushed back. Many argued that AI is not like another camera, criticized the way AI models draw from other people’s work, and said that Deakins doesn’t have to worry about keeping his job. Deakins’s statement and the forceful replies revealed just how fundamentally different his understanding of cinematography and AI is from that of many working filmmakers.

THE VILLAGE, Roger Deakins, 2004, Image credit: Buena Vista

THE VILLAGE, Roger Deakins, 2004, Image credit: Buena Vista

For nearly two decades as a cinematographer and educator at schools like the AFI Conservatory and Columbia University, I distilled a successful cinematographer into the following three traits: technical skill, clarity of intention, and communication. In art forms where the artist works alone (like painting) communication matters far less. Filmmaking, however, is collaborative. In leadership roles like the cinematographer’s, where you’re not the one operating most of the tools, technical knowledge isn’t the primary skill. It matters mainly so you can communicate your intention to the artists and technicians who do the hands-on work. In fact, as our tools evolve, technical skill becomes even less central. Few cinematographers today understand digital cameras with the same depth that most cinematographers once understood photochemical exposure and processing. As reliance on technology increases, intention and communication become the core traits of leadership in filmmaking. For Deakins, AI is simply another tool in the progression of technology, and he sees the cinematographer’s role primarily in realizing a director’s intention rather than using any particular tool.

But many filmmakers have a different view of AI than Deakins. Its arrival adds a new twist to the question of technical skill in filmmaking. If AI simply makes image-making easier, then it follows the same pattern as the introduction of sound, color, and video—each one a major technological shift that reshaped filmmaking and replaced certain jobs with others. Using AI would be “cheating” in the same way photography once “cheated” painters. Filmmakers should worry about their job only if AI encroaches into intention and communication. At that point, the issue isn’t whether AI makes image-making easier, but whether it changes the creative choices themselves.

When filmmakers stop making choices, the problem isn’t technology

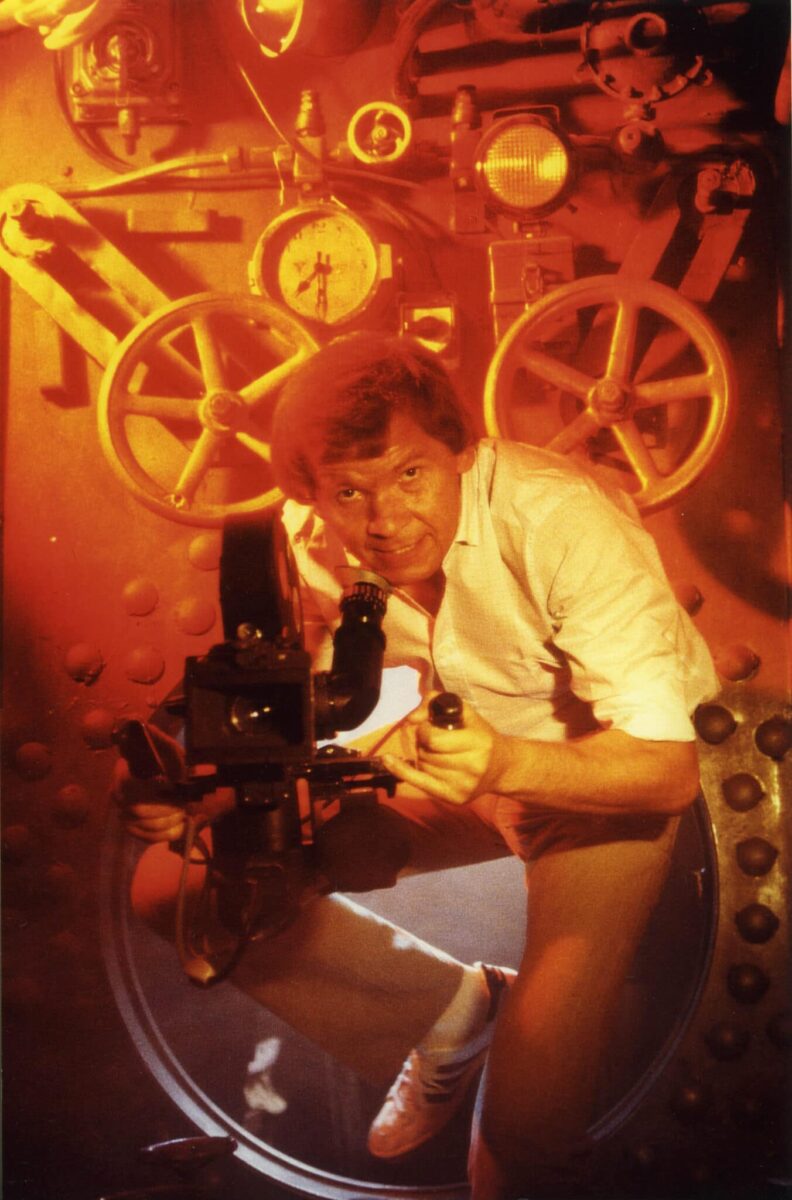

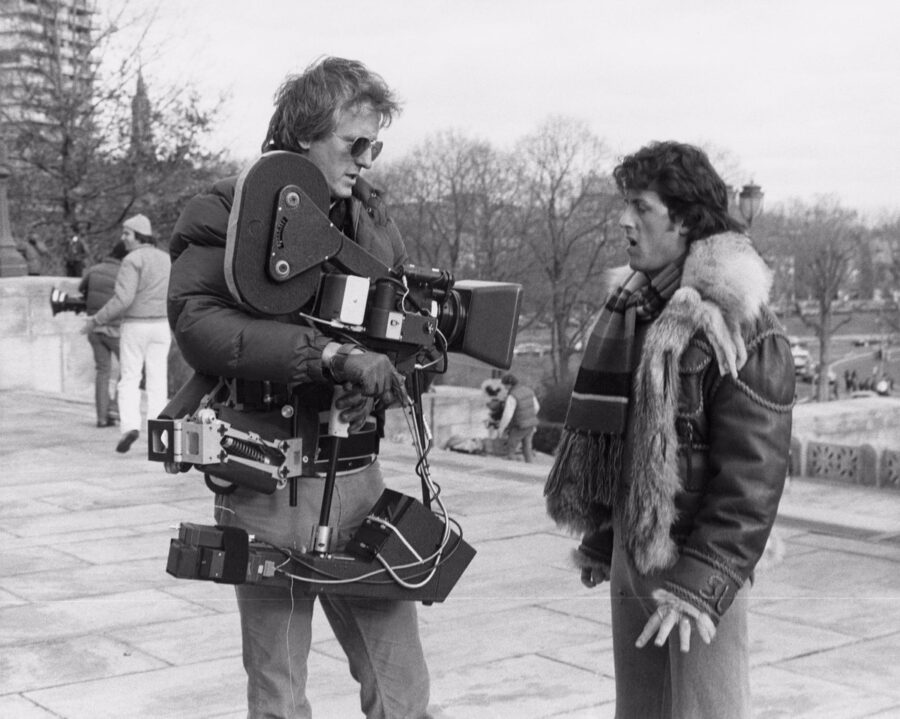

It’s difficult to separate between technology and creativity, since they are not distinct forces. Many innovations began with creative demands (for Das Boot, ARRI modified its cameras to fit the filmmakers’ needs, which inspired a new generation of cameras). Many creative ideas started with the arrival of a new technology (Garrett Brown’s Steadicam introduced a new visual style that shaped films like Rocky and The Shining). For AI to be different from earlier innovations, it would need to go beyond influencing a filmmaker’s intention. It would have to participate in the act of deciding itself, and even control the motivation behind those decisions. If AI becomes the one determining the story and “what to say,” to borrow Deakins’s own words, then even he would think twice.

DP Jost Vacano on set of “Das Boot”. Image credit: Jost Vacano archive

DP Jost Vacano on set of “Das Boot”. Image credit: Jost Vacano archive Steadicam Inventor Garett Brown on the set of Rocky. Image credit: unknown

Steadicam Inventor Garett Brown on the set of Rocky. Image credit: unknown

How can we tell if AI, and not an artist, is making decisions? AI-generated work (including AI filmmaking) available online appears better every day, but we can’t see which parts represent the artist’s choice and which are the result of losing a battle with the software. One way to tell is to try generating images with AI ourselves, but with the kind of specific intent filmmakers normally bring to their work. If tools like Midjourney or Sora are meant to replace cinematographers, production designers, or wardrobe artists (professionals who work by specifying precise details like lens choice or fabric type) then we should be able to control AI-generated images with the same level of precision. In reality, that level of control is not yet possible. Filmmaker Bennett Miller (Moneyball, Capote) generated over 100,000 images to get 20 usable ones, calling it “really an editing process.” Patrick Cederberg, one of the first filmmakers given access to Sora, said: “Control is still the thing that is the most desirable and also the most elusive at this point.”

When you use AI filmmaking, AI image making and other AI tools with a clear intention, the real problem that emerges isn’t technological but one artists have always faced. If you abandon your intention because you lack the skill to create it, you’re not giving in to technology; you’re giving in to mediocrity. In a world where intention is replaced with convenience, the selection of a lens, type of wallpaper or thickness of the actor’s eyeliner stop being artistic choices. Make no mistake: good cinematographers, production designers, and makeup artists make these decisions in service of the director’s intention, even if they never talk about it directly. When AI is given freedom to make these choices, it does not draw them from the director’s intention, but from convention. That’s why the early versions of the AI image inspired by The Reading did not achieve the effect I wanted.

How to solve film’s ‘good enough’ problem

Watch the end credits of any film and it becomes clear just how many artists and technicians are required to bring it to life. Some roles will inevitably disappear, just like the theater pianists of the silent era and the runners who once delivered dailies. The roles that stay will not be threatened by technology itself, but by the belief that a movie is ‘good enough’ even if some creative decisions do not align with the director’s intentions. It’s an approach that directly contradicts how great artists work—authors agonize over every comma, composers over every note. If you’re in a creative role, this is the moment to decide how technology fits into your work. Maintaining creative control may require resisting the temptation to let AI make the decisions for you. That human-centered approach to technology is at the heart of my forthcoming book, Cinematography Beyond Technique (available at Routledge or Amazon).

Filmmakers have always conflated the art of cinematography with the tools used to express it. In my book, I offer a story-driven approach to cinematography that prioritizes the director’s intention before any technical choices. I believe this approach is crucial as filmmaking evolves with AI, especially since most viewers of AI‑generated work don’t appreciate the gap between the work they see and the intention behind it (or how much that intention shapes works they value). My advice to filmmakers is to embrace emerging technology instead of trying to escape it, but to use it in a way that preserves their creative intention. ‘Good enough’ has never been a lasting creative strategy, even during moments when it briefly became the norm (think of the Canon 5D era with its limited dynamic range and moiré that everyone tolerated). Once the excitement around a new tool fades, it’s the artists with original ideas and the skill to express them who remain essential, not those who just know how to operate the equipment. AI only makes that distinction sharper. It can help brainstorm, draft, and even generate original work, but if you let it make the decisions for you, it’s no different from handing those choices to a human assistant—the intention stops being yours. The AI image inspired by Morisot proved the point: our job is still deciding what the story should mean and having the skill to express it clearly.

Tal Lazar is a cinematographer and educator who has created filmmaking workshops for the American Film Institute Conservatory, Columbia University School of the Arts, Sundance Institute’s Collab, Berklee College of Music Online and other film programs. Some of his courses are available on our filmmaking education platform MZed. His forthcoming book, Cinematography Beyond Technique, aims to make cinematography accessible to filmmakers of all levels.

Featured image shows cinematographer Roger Deakins, courtesy of Lionsgate Studios.